field bindweed Convolvulus arvensis L.

field bindweed Convolvulus arvensis L.

field bindweed Convolvulus arvensis L.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

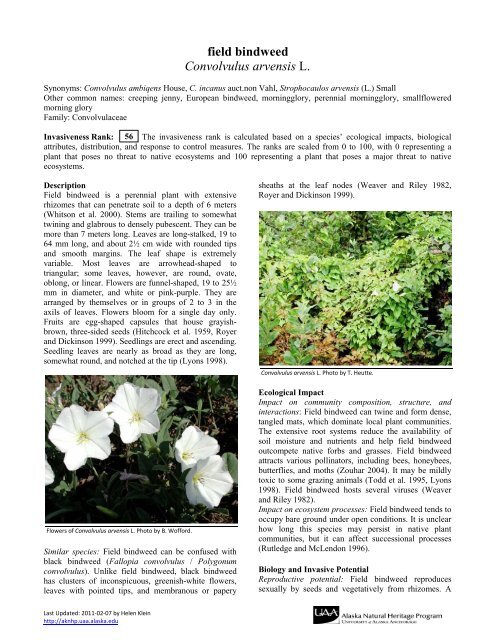

<strong>field</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong><strong>Convolvulus</strong> <strong>arvensis</strong> L.Synonyms: <strong>Convolvulus</strong> ambiqens House, C. incanus auct.non Vahl, Strophocaulos <strong>arvensis</strong> (L.) SmallOther common names: creeping jenny, European <strong>bindweed</strong>, morningglory, perennial morningglory, smallfloweredmorning gloryFamily: ConvolvulaceaeInvasiveness Rank: 56 The invasiveness rank is calculated based on a species’ ecological impacts, biologicalattributes, distribution, and response to control measures. The ranks are scaled from 0 to 100, with 0 representing aplant that poses no threat to native ecosystems and 100 representing a plant that poses a major threat to nativeecosystems.DescriptionField <strong>bindweed</strong> is a perennial plant with extensiverhizomes that can penetrate soil to a depth of 6 meters(Whitson et al. 2000). Stems are trailing to somewhattwining and glabrous to densely pubescent. They can bemore than 7 meters long. Leaves are long-stalked, 19 to64 mm long, and about 2½ cm wide with rounded tipsand smooth margins. The leaf shape is extremelyvariable. Most leaves are arrowhead-shaped totriangular; some leaves, however, are round, ovate,oblong, or linear. Flowers are funnel-shaped, 19 to 25½mm in diameter, and white or pink-purple. They arearranged by themselves or in groups of 2 to 3 in theaxils of leaves. Flowers bloom for a single day only.Fruits are egg-shaped capsules that house grayishbrown,three-sided seeds (Hitchcock et al. 1959, Royerand Dickinson 1999). Seedlings are erect and ascending.Seedling leaves are nearly as broad as they are long,somewhat round, and notched at the tip (Lyons 1998).Flowers of <strong>Convolvulus</strong> <strong>arvensis</strong> L. Photo by B. Wofford.Similar species: Field <strong>bindweed</strong> can be confused withblack <strong>bindweed</strong> (Fallopia convolvulus / Polygonumconvolvulus). Unlike <strong>field</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong>, black <strong>bindweed</strong>has clusters of inconspicuous, greenish-white flowers,leaves with pointed tips, and membranous or paperysheaths at the leaf nodes (Weaver and Riley 1982,Royer and Dickinson 1999).<strong>Convolvulus</strong> <strong>arvensis</strong> L. Photo by T. Heutte.Ecological ImpactImpact on community composition, structure, andinteractions: Field <strong>bindweed</strong> can twine and form dense,tangled mats, which dominate local plant communities.The extensive root systems reduce the availability ofsoil moisture and nutrients and help <strong>field</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong>outcompete native forbs and grasses. Field <strong>bindweed</strong>attracts various pollinators, including bees, honeybees,butterflies, and moths (Zouhar 2004). It may be mildlytoxic to some grazing animals (Todd et al. 1995, Lyons1998). Field <strong>bindweed</strong> hosts several viruses (Weaverand Riley 1982).Impact on ecosystem processes: Field <strong>bindweed</strong> tends tooccupy bare ground under open conditions. It is unclearhow long this species may persist in native plantcommunities, but it can affect successional processes(Rutledge and McLendon 1996).Biology and Invasive PotentialReproductive potential: Field <strong>bindweed</strong> reproducessexually by seeds and vegetatively from rhizomes. ALast Updated: 2011-02-07 by Helen Kleinhttp://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu

single plant can produce between 12 and 500 seeds peryear (Weaver and Riley 1982, Royer and Dickinson1999). Seed banks are extremely persistent. Seeds canlie dormant in the soil for more than 50 years (Timmons1949, Lyons 1998, Whitson et al. 2000).Role of disturbance in establishment: Field <strong>bindweed</strong> isan early successional species that establishes easily onbare ground or in disturbed natural communities. Seedsgerminate better on bare ground than on sites with litteror vegetation (Zouhar 2004).Potential for long-distance dispersal: Seeds land nearthe parent plant but can be dispersed farther by water,birds, or animals (Harmon and Keim 1934, Proctor1968, Weaver and Riley 1982, Zouhar 2004).Potential to be spread by human activity: Seeds can bedispersed by vehicles and machinery or in contaminatedfarm and garden seed. Field <strong>bindweed</strong> is planted as anornamental ground cover and in hanging baskets(Zouhar 2004).Germination requirements: Peak germination occurs inlate spring or early summer. Under laboratoryconditions, the optimal temperatures for germination of<strong>field</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong> ranged from 20°C to 35°C. Seed coatscan become permeable to water by exposure to moist airor fluctuating soil temperatures, by mechanical abrasion(especially during cultivation), or by passage throughthe digestive tract of mammals and birds (Weaver andRiley 1982).Growth requirements: The optimal growth conditionsfor <strong>field</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong> are strong sunlight and moderate tolow moisture. This plant grows best on rich, fertile soilsbut may persist on nutrient-poor gravel (Rutledge andMcLendon 1996). Field <strong>bindweed</strong> is cold tolerant.Freezing temperatures kill shoots, but roots andrhizomes can withstand temperatures as low as -6°C(Dexter 1937).Congeneric weeds: Hollyhock <strong>bindweed</strong> (<strong>Convolvulus</strong>althaeoides) is known to occur as a non-native weed inNorth America (DiTomaso and Healy 2007, ITIS 2010).Legal ListingsHas not been declared noxiousListed noxious in AlaskaListed noxious by other states (AR, AZ, CA, CO, HI,IA, ID, KS, MI, MN, MO, MT, ND, NM, OR, SD,References:AKEPIC database. Alaska Exotic Plant InformationClearinghouse Database. 2010. Available:http://akweeds.uaa.alaska.edu/Alaska Administrative Code. Title 11, Chapter 34. 1987.Alaska Department of Natural Resources.Division of Agriculture.Dexter, S.T. 1937. The winter hardiness of weeds.Journal of the American Society of Agronomy29: 512-517.TX, UT, WA, WI, WY)Federal noxious weedListed noxious in Canada or other countries (AB, MB,NS, QC, SK)Distribution and abundanceField <strong>bindweed</strong> grows in temperate, tropical, andMediterranean climates (Lyons 1998, Gubanov et al.2004). It is especially common in cereal crops, orchards,and vineyards. In many areas, <strong>field</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong> isconsidered to be one of the most detrimental agriculturalweeds (Hitchcock et al. 1959). Field <strong>bindweed</strong> can alsobe found in roadsides, ditches, stream banks, andlakeshores (Lyons 1998).Native and current distribution: Field <strong>bindweed</strong> isnative to Europe and Asia but currently has acosmopolitan distribution between the 60°N and 45°Slatitudes. It is common in the United States and Canada,except in the extreme Southeast, New Mexico, Arizona,Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island. Field<strong>bindweed</strong> has been documented from the PacificMaritime and Interior-Boreal ecogeographic regions ofAlaska (AKEPIC 2010).Pacific MaritimeInterior- BorealArctic-AlpineCollection SiteDistribution of <strong>field</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong> in AlaskaManagementField <strong>bindweed</strong> is difficult to control due to its extensiveroot systems and long-lived seed banks. Mechanicalcontrol is not effective because plants can regeneratefrom the rhizomes. Herbicides are generally the mosteffective control method. No biological control agentsare currently available (Rutledge and McLendon 1996,Elmore and Cudney 2003).DiTomaso, J., and E. Healy. 2007. Weeds of Californiaand Other Western States. Vol. 1. University ofCalifornia Agriculture and Natural ResourcesCommunication Services, Oakland, CA. 834 p.Elmore, C.L. and D.W. Cudney. 2003. Field <strong>bindweed</strong>.Integrated pest management for homegardeners and landscape professionals. Pestnotes. Davis (CA): University of California,Agriculture and Natural Resources. PublicationLast Updated: 2011-02-07 by Helen Kleinhttp://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu

number 7462. 4 p.Gubanov IA, Kiseleva KV, Novikov VS, TihomirovVN. An Illustrated identification book of theplants of Middle Russia, Vol. 3: Angiosperms(dicots: archichlamydeans). Moscow: Instituteof Technological Researches; 2004. 520 p.Harmon, G.W. and F.D. Keim. 1934. The percentageand viability of weed seeds recovered in thefeces of farm animals and their longevity whenburied in manure. Journal of the AmericanSociety of Agronomy 26: 762-767.Hitchcock, C.L., A. Cronquist, and M. Ownbey. 1959.Vascular plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part4: Ericaceae through Campanulaceae. Seattle,WA: University of Washington Press. 510 p.Invaders Database System. 2010. University ofMontana. Missoula, MT.http://invader.dbs.umt.edu/ITIS. 2010. Integrated Taxonomic Information System.http://www.itis.gov/Lyons, K.E. 1998. Element stewardship abstract for<strong>Convolvulus</strong> <strong>arvensis</strong> L. Field <strong>bindweed</strong>. TheNature Conservancy: Arlington, Virginia.Proctor, V.W. 1968. Long-distance dispersal of seeds byretention in digestive tract of birds. Science160: 321-322.Royer, F., and R. Dickinson. 1999. Weeds of theNorthern U.S. and Canada. The University ofAlberta press. 434 pp.Rutledge, C.R., and T. McLendon. 1996. AnAssessment of Exotic Plant Species of RockyMountain National Park. Department ofRangeland Ecosystem Science, Colorado StateUniversity. 97 pp. Northern Prairie WildlifeResearch Center Home Page.http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/plants/explant/index.htm (Version 15DEC98).Timmons, F.L. 1949. Duration of viability of <strong>bindweed</strong>seed under <strong>field</strong> conditions and experimentalresults in the control of <strong>bindweed</strong> seedlings.Agronomy Journal 41: 130-133.Todd, F.G., F.R. Stermitz, P. Schultheis, A.P. Knight,and J. Traub-Dargatz. 1995. Tropane alkaloidsand toxicity of <strong>Convolvulus</strong> <strong>arvensis</strong>.Phytochemistry 39(2): 301-303.USDA, NRCS. 2006. The PLANTS Database, Version3.5 (http://plants.usda.gov). Data compiledfrom various sources by Mark W. Skinner.National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA70874-4490 USA.Weaver, S.E. and W.R. Riley. 1982. The biology ofCanadian weeds. 53. <strong>Convolvulus</strong> <strong>arvensis</strong> L.Canadian Journal of Plant Science 62: 461-472.Whitson, T. D., L. C. Burrill, S. A. Dewey, D. W.Cudney, B. E. Nelson, R. D. Lee, R. Parker.2000. Weeds of the West. The Western Societyof Weed Science in cooperation with theWestern United States Land Grant Universities,Cooperative Extension Services. University ofWyoming. Laramie, Wyoming. 630 pp.Zouhar, K. 2004. <strong>Convolvulus</strong> <strong>arvensis</strong>. In: Fire EffectsInformation System, [Online]. U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky MountainResearch Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory(Producer). Available:http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2005,January 12].Last Updated: 2011-02-07 by Helen Kleinhttp://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu