black bindweed Fallopia convolvulus - Alaska Natural Heritage ...

black bindweed Fallopia convolvulus - Alaska Natural Heritage ...

black bindweed Fallopia convolvulus - Alaska Natural Heritage ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

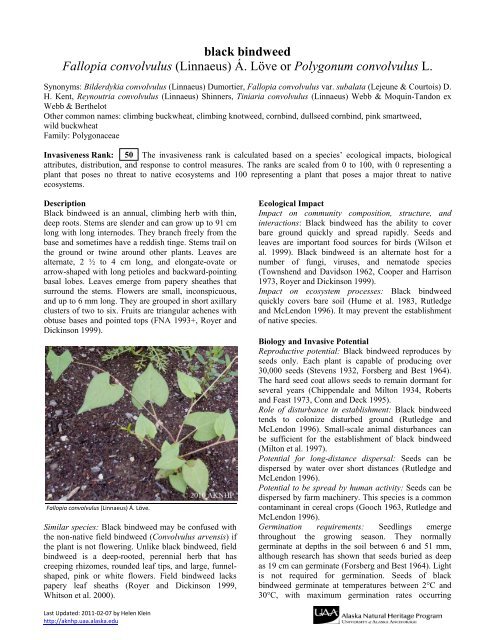

lack <strong>bindweed</strong><strong>Fallopia</strong> <strong>convolvulus</strong> (Linnaeus) Á. Löve or Polygonum <strong>convolvulus</strong> L.Synonyms: Bilderdykia <strong>convolvulus</strong> (Linnaeus) Dumortier, <strong>Fallopia</strong> <strong>convolvulus</strong> var. subalata (Lejeune & Courtois) D.H. Kent, Reynoutria <strong>convolvulus</strong> (Linnaeus) Shinners, Tiniaria <strong>convolvulus</strong> (Linnaeus) Webb & Moquin-Tandon exWebb & BerthelotOther common names: climbing buckwheat, climbing knotweed, cornbind, dullseed cornbind, pink smartweed,wild buckwheatFamily: PolygonaceaeInvasiveness Rank: 50 The invasiveness rank is calculated based on a species’ ecological impacts, biologicalattributes, distribution, and response to control measures. The ranks are scaled from 0 to 100, with 0 representing aplant that poses no threat to native ecosystems and 100 representing a plant that poses a major threat to nativeecosystems.DescriptionBlack <strong>bindweed</strong> is an annual, climbing herb with thin,deep roots. Stems are slender and can grow up to 91 cmlong with long internodes. They branch freely from thebase and sometimes have a reddish tinge. Stems trail onthe ground or twine around other plants. Leaves arealternate, 2 ½ to 4 cm long, and elongate-ovate orarrow-shaped with long petioles and backward-pointingbasal lobes. Leaves emerge from papery sheathes thatsurround the stems. Flowers are small, inconspicuous,and up to 6 mm long. They are grouped in short axillaryclusters of two to six. Fruits are triangular achenes withobtuse bases and pointed tops (FNA 1993+, Royer andDickinson 1999).<strong>Fallopia</strong> <strong>convolvulus</strong> (Linnaeus) Á. Löve.Similar species: Black <strong>bindweed</strong> may be confused withthe non-native field <strong>bindweed</strong> (Convolvulus arvensis) ifthe plant is not flowering. Unlike <strong>black</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong>, field<strong>bindweed</strong> is a deep-rooted, perennial herb that hascreeping rhizomes, rounded leaf tips, and large, funnelshaped,pink or white flowers. Field <strong>bindweed</strong> lackspapery leaf sheaths (Royer and Dickinson 1999,Whitson et al. 2000).Ecological ImpactImpact on community composition, structure, andinteractions: Black <strong>bindweed</strong> has the ability to coverbare ground quickly and spread rapidly. Seeds andleaves are important food sources for birds (Wilson etal. 1999). Black <strong>bindweed</strong> is an alternate host for anumber of fungi, viruses, and nematode species(Townshend and Davidson 1962, Cooper and Harrison1973, Royer and Dickinson 1999).Impact on ecosystem processes: Black <strong>bindweed</strong>quickly covers bare soil (Hume et al. 1983, Rutledgeand McLendon 1996). It may prevent the establishmentof native species.Biology and Invasive PotentialReproductive potential: Black <strong>bindweed</strong> reproduces byseeds only. Each plant is capable of producing over30,000 seeds (Stevens 1932, Forsberg and Best 1964).The hard seed coat allows seeds to remain dormant forseveral years (Chippendale and Milton 1934, Robertsand Feast 1973, Conn and Deck 1995).Role of disturbance in establishment: Black <strong>bindweed</strong>tends to colonize disturbed ground (Rutledge andMcLendon 1996). Small-scale animal disturbances canbe sufficient for the establishment of <strong>black</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong>(Milton et al. 1997).Potential for long-distance dispersal: Seeds can bedispersed by water over short distances (Rutledge andMcLendon 1996).Potential to be spread by human activity: Seeds can bedispersed by farm machinery. This species is a commoncontaminant in cereal crops (Gooch 1963, Rutledge andMcLendon 1996).Germination requirements: Seedlings emergethroughout the growing season. They normallygerminate at depths in the soil between 6 and 51 mm,although research has shown that seeds buried as deepas 19 cm can germinate (Forsberg and Best 1964). Lightis not required for germination. Seeds of <strong>black</strong><strong>bindweed</strong> germinate at temperatures between 2°C and30°C, with maximum germination rates occurringLast Updated: 2011-02-07 by Helen Kleinhttp://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu

etween 5°C and 15°C.Growth requirements: Black <strong>bindweed</strong> grows in a widerange of soil types (Hume et al. 1983). Shade usuallysuppresses the growth of <strong>black</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong> (Haman andPeeper 1983).Congeneric weeds: Prostrate knotweed (Polygonumaviculare), Asiatic tearthumb (P. perfoliatum),Himalayan knotweed (P. polystachyum), Japaneseknotweed (<strong>Fallopia</strong> japonica / Polygonum cuspidatum),giant knotweed (<strong>Fallopia</strong> sachalinensis / Polygonumsachalinense), Bohemian knotweed (<strong>Fallopia</strong>×bohemica / Polygonum ×bohemicum), spottedladysthumb (Persicaria maculosa / Polygonumpersicaria), and curlytop knotweed (Persicarialapathifolia / Polygonum lapathifolium) are considerednoxious weeds in one or more states of the U.S. orprovinces of Canada (USDA, NRSC 2006, Invaders2010). A number of Polygonum species native to NorthAmerica have weedy habits and are listed as noxiousweeds in some states of the U.S. The species listedabove are closely related taxa and can be consideredcongeneric weeds, although the latest taxonomyconsiders them to be members of three different genera:Polygonum, <strong>Fallopia</strong>, and Persicaria (FNA 1993+).Legal ListingsHas not been declared noxiousListed noxious in <strong>Alaska</strong>Listed noxious by other states (OK)Federal noxious weedListed noxious in Canada or other countries (MB, QC,SK)Distribution and abundanceBlack <strong>bindweed</strong> is a common weed in cultivated fields,gardens, and orchards. It may also be found in wasteareas, thickets, and roadsides. It occasionally grows inriverbanks and pastures (Hume 1983).Native and current distribution: Black <strong>bindweed</strong> isnative to Eurasia. It grows throughout Canada and theU.S. (Royer and Dickinson 1999). It has also beenintroduced to Africa, South America, Australia, NewZealand, and Oceania (Hultén 1968, USDA, ARS2003). Black <strong>bindweed</strong> has been documented from allthree ecogeographic regions of <strong>Alaska</strong> (Hultén 1968,AKEPIC 2010, UAM 2010).Pacific MaritimeInterior-BorealArctic-AlpineCollection SiteDistribution of <strong>black</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong> in <strong>Alaska</strong>.ManagementMechanical methods are only somewhat effective atcontrolling infestations of <strong>black</strong> <strong>bindweed</strong>. A number ofchemicals are recommended for the control of thisspecies. Several pathogenic fungi have been studied aspotential biological control agents (Mortensen andMolloy 1993, Dal-Bello and Carranza 1995).References:AKEPIC database. <strong>Alaska</strong> Exotic Plant InformationClearinghouse Database. 2010. Available:http://akweeds.uaa.alaska.edu/<strong>Alaska</strong> Administrative Code. Title 11, Chapter 34. 1987.<strong>Alaska</strong> Department of <strong>Natural</strong> Resources.Division of Agriculture.Chippindale, H.G. and W.E.J. Milton. 1934. On theviable seeds present in the soil beneath pasture.The Journal of Ecology 22(2): 508-531.Conn, J.S. and R.E. Deck. 1995. Seed viability anddormancy of 17 weed species after 9.7 years ofburial in <strong>Alaska</strong>. Weed Science 43: 583-585.Cooper, J.I. and B.D. Harrison. 1973. The role of weedhosts and the distribution and activity ofvector nematodes in the ecology oftobacco rattle virus. Annals of AppliedBiology 73: 53-66.Dal-Bello, G.M. and M.R. Carranza. 1995. Weeddiseases in La Plata area II. Identification ofpathogens with potential for weed biocontrolprogrammes. Revista de la Facultad deAgronomia, La Plata 71(1): 7-14.Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds.1993+. Flora of North America North ofMexico. 7+ vols. New York and Oxford.Forsberg, D.E. and K.F. Best. 1964. The emergence andplant development of wild buckwheat(Polygonum <strong>convolvulus</strong>). Canadian Journal ofPlant Science 44: 100-103.Gooch, S.M.S. 1963. The occurrence of weed seeds insamples tested by the official seed testingstation, 1960-1. Journal of the National Instituteof Agricultural Botany 9(3): 353-371.Haman, C.D. and T.F. Peeper. 1983. The effect of shadeon wild buckwheat. Proceedings, SouthernWeed Science Society. P. 348.Hultén, E. 1968. Flora of <strong>Alaska</strong> and NeighboringTerritories. Stanford University Press, Stanford,CA. 1008 p.Hume, L., J. Martinez and K. Best. 1983. The biology ofLast Updated: 2011-02-07 by Helen Kleinhttp://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu

Canadian weeds. 60. Polygonum <strong>convolvulus</strong> L.Canadian Journal of Plant Science 63: 959-971.Invaders Database System. 2010. University ofMontana. Missoula, MT.http://invader.dbs.umt.edu/Milton, S.J., W.R.J. Dean and S. Klotz. 1997. Effects ofsmall-scale animal disturbances on plantassemblages of set-aside land in CentralGermany. Journal of Vegetation Science 8: 45-54.Mortensen, K. and M.M. Molloy. 1993. Survey forseed-borne diseases on weed species fromscreening samples obtained from seed cleaningplants across Canada in 1987/88. CanadianPlant Disease Survey 73: 129-136.Roberts, H.A. and P.M. Feast. 1973. Emergence andlongevity of seeds of annual weeds in cultivatedand undisturbed soil. The Journal of AppliedEcology 10(1): 133-143.Royer, F., and R. Dickinson. 1999. Weeds of theNorthern U.S. and Canada. The University ofAlberta press. 434 pp.Rutledge, C.R., and T. McLendon. 1996. AnAssessment of Exotic Plant Species of RockyMountain National Park. Department ofRangeland Ecosystem Science, Colorado StateUniversity. 97 pp. Northern Prairie WildlifeResearch Center Home Page.http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/plants/explant/index.htm (Version 15DEC98).Stevens, O.A. 1932. The number and weight of seedsproduced by weeds. American Journal ofBotany 19(9): 784-794.Townshend, J.L. and T.R. Davidson. 1962. Some weedhosts of the northern root-knot nematode,Meloidogyne hapla Chitwood, 1949, in Ontario.Canadian Journal of Botany 40: 543-548.UAM. 2010. University of <strong>Alaska</strong> Museum, Universityof <strong>Alaska</strong> Fairbanks. Available:http://arctos.database.museum/home.cfmUSDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program.Germplasm Resources Information Network -(GRIN) [Online Database]. NationalGermplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville,Maryland. URL:http://www.arsgrin.gov/var/apache/cgibin/npgs/html/taxon.pl?300618 [December 13, 2004].USDA, NRCS. 2006. The PLANTS Database, Version3.5 (http://plants.usda.gov). Data compiledfrom various sources by Mark W. Skinner.National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA70874-4490 USA.Whitson, T. D., L. C. Burrill, S. A. Dewey, D. W.Cudney, B. E. Nelson, R. D. Lee, R. Parker.2000. Weeds of the West. The Western Societyof Weed Science in cooperation with theWestern United States Land Grant Universities,Cooperative Extension Services. University ofWyoming. Laramie, Wyoming. 630 pp.Wilson, J.D., A.J. Morris, B.E. Arroyo, S.C. Clark andR.B. Bradbury. 1999. A review of theabundance and diversity of invertebrate andplant foods of granivorous birds in northernEurope in relation to agricultural change.Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 75:13-30.Last Updated: 2011-02-07 by Helen Kleinhttp://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu