Pinguicula vulgaris - Michigan Natural Features Inventory - Michigan ...

Pinguicula vulgaris - Michigan Natural Features Inventory - Michigan ...

Pinguicula vulgaris - Michigan Natural Features Inventory - Michigan ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

utterwort, Page 1<br />

<strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong> L. butterwort<br />

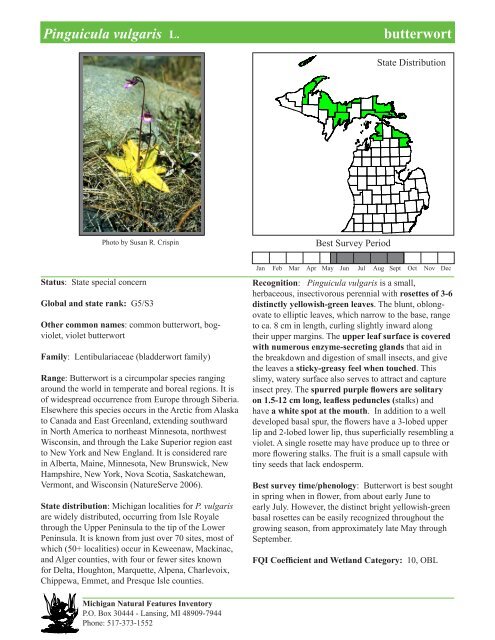

Photo by Susan R. Crispin<br />

Status: State special concern<br />

Global and state rank: G5/S3<br />

Other common names: common butterwort, bogviolet,<br />

violet butterwort<br />

Family: Lentibulariaceae (bladderwort family)<br />

Range: Butterwort is a circumpolar species ranging<br />

around the world in temperate and boreal regions. It is<br />

of widespread occurrence from Europe through Siberia.<br />

Elsewhere this species occurs in the Arctic from Alaska<br />

to Canada and East Greenland, extending southward<br />

in North America to northeast Minnesota, northwest<br />

Wisconsin, and through the Lake Superior region east<br />

to New York and New England. It is considered rare<br />

in Alberta, Maine, Minnesota, New Brunswick, New<br />

Hampshire, New York, Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan,<br />

Vermont, and Wisconsin (NatureServe 2006).<br />

State distribution: <strong>Michigan</strong> localities for P. <strong>vulgaris</strong><br />

are widely distributed, occurring from Isle Royale<br />

through the Upper Peninsula to the tip of the Lower<br />

Peninsula. It is known from just over 70 sites, most of<br />

which (50+ localities) occur in Keweenaw, Mackinac,<br />

and Alger counties, with four or fewer sites known<br />

for Delta, Houghton, Marquette, Alpena, Charlevoix,<br />

Chippewa, Emmet, and Presque Isle counties.<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Features</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong><br />

P.O. Box 30444 - Lansing, MI 48909-7944<br />

Phone: 517-373-1552<br />

Jan<br />

Feb<br />

Mar<br />

Apr<br />

Best Survey Period<br />

May<br />

Jun<br />

Jul<br />

State Distribution<br />

Aug<br />

Sept<br />

Oct<br />

Nov<br />

Dec<br />

Recognition: <strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong> is a small,<br />

herbaceous, insectivorous perennial with rosettes of 3-6<br />

distinctly yellowish-green leaves. The blunt, oblongovate<br />

to elliptic leaves, which narrow to the base, range<br />

to ca. 8 cm in length, curling slightly inward along<br />

their upper margins. The upper leaf surface is covered<br />

with numerous enzyme-secreting glands that aid in<br />

the breakdown and digestion of small insects, and give<br />

the leaves a sticky-greasy feel when touched. This<br />

slimy, watery surface also serves to attract and capture<br />

insect prey. The spurred purple flowers are solitary<br />

on 1.5-12 cm long, leafless peduncles (stalks) and<br />

have a white spot at the mouth. In addition to a well<br />

developed basal spur, the flowers have a 3-lobed upper<br />

lip and 2-lobed lower lip, thus superficially resembling a<br />

violet. A single rosette may have produce up to three or<br />

more flowering stalks. The fruit is a small capsule with<br />

tiny seeds that lack endosperm.<br />

Best survey time/phenology: Butterwort is best sought<br />

in spring when in flower, from about early June to<br />

early July. However, the distinct bright yellowish-green<br />

basal rosettes can be easily recognized throughout the<br />

growing season, from approximately late May through<br />

September.<br />

FQI Coefficient and Wetland Category: 10, OBL

utterwort, Page 2<br />

Habitat: <strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong> is a well-known<br />

calciphile (favoring alkaline or lime-rich habitats) and<br />

as with most insectivorous plants, prefers wet substrates.<br />

It is found in moist alkaline rock crevices and outcrops;<br />

rocky or gravelly shores, sandy, interdunal shoreline<br />

flats; marshy soils near bogs, wet alvars, and the marly,<br />

calcareous soils of coastal and northern fens. It also<br />

occurs in Lake Superior coastal areas where it inhabits<br />

volcanic bedrock lakeshore areas, favoring basalts and<br />

conglomerate bedrock types. Most <strong>Michigan</strong> locations<br />

are along Great Lakes shores, particularly on rocky,<br />

wet beaches and nearshore wetlands and interdunal<br />

areas. Primula mistassinica (birds-eye primrose) is a<br />

common associate as are numerous other herbs such as<br />

Drosera rotundifolia (round-leaved sundew), D. linearis<br />

(linear-leaved sundew), Sarracenia purpurea (pitcherplant),<br />

Utricularia intermedia (flat-leaved bladderwort),<br />

U. cornuta (horned bladderwort), Castilleja coccinea<br />

(Indian paintbrush), Parnassia glauca grass-of-<br />

Parnassus), Tofieldia glutinosa (false asphodel), and<br />

Gentianopsis procera (small fringed gentian). The<br />

rare Solidago houghtonii (Houghton’s goldenrod) is<br />

an expected associate in the Straits region, as might be<br />

Empetrum nigrum (black crowberry) and other rarities<br />

such as the similarly boreal Erigeron hyssopifolius<br />

(hyssop-leaved fleabane) and Carex scirpoidea (bulrush<br />

sedge). These associates are similar to those found with<br />

butterwort in shoreline limestone pavement or wet alvar<br />

sites.<br />

In bedrock shoreline communities in the more<br />

northern portion of its <strong>Michigan</strong> range, butterwort<br />

occurs on alkaline basalts, volcanic conglomerates,<br />

and occasionally wet sandstones, where associates<br />

include such species as Campanula rotundifolia<br />

(harebell), Deschampsia cespitosa (hair grass),<br />

Festuca saximontana (fescue), Artemisia campestris<br />

(wormwood), Carex viridula (sedge), and Solidago<br />

simplex (Gillman’s goldenrod).<br />

Biology: <strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong> is an insectivorous,<br />

perennial herb that secretes mucilaginous fluids and<br />

digestive enzymes through two types of leaf glands.<br />

Small insects first adhere to the mucilaginous fluids<br />

secreted by the stalked ‘sticky’ glands. Their struggling<br />

movements, which stimulate increased production of<br />

the mucilaginous fluids, then cause the secretion of<br />

enzyme-containing fluids from the ‘sessile’ glands. It<br />

is the latter secretion that is primarily responsible for<br />

insect digestion and nutrient absorption by the plant.<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Features</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong><br />

P.O. Box 30444 - Lansing, MI 48909-7944<br />

Phone: 517-373-1552<br />

Upon stimulation, the leaves also roll inward from their<br />

margins; this is thought to minimize the loss of prey and<br />

also aid in enzymatic degradation by increasing the leaf<br />

surface area in contact with the prey. This in-rolling may<br />

also reduce the loss of enzymes and nutrients through<br />

seepage or by preventing exposure to rainfall.<br />

Flowering plants can be found in late May through<br />

June and into early July, followed by the formation of<br />

a capsule containing several seeds, typically from early<br />

July through August. During winter, butterwort persists<br />

as a winter resting bud known as a hibernaculum<br />

that begins to form in the center of the rosette by late<br />

summer. This bud is entirely without roots and therefore<br />

may be dispersed by water movement, wind, or<br />

possibly animal activity. The small scale-leaves of the<br />

hibernaculum contain starches that nurture the enclosed<br />

seedling during spring emergence when new leaves and<br />

roots are forming.<br />

Biologists have long been interested in carnivorous<br />

plants, particularly with regard to the topics of<br />

resource allocation, reproduction, plant demography<br />

(the structure and dynamics of populations), and the<br />

evolution of carnivory as an adaptation to low nutrient<br />

availability. Owing to the extensive nature of this<br />

literature, which cannot be adequately summarized<br />

here, the reader is referred to the following references<br />

for further information on these topics: Méndez and<br />

Karlsson (2005), Méndez and Karlsson (2004), Eckstein<br />

and Karlsson (2001), Worley and Harder (1999), Thorén<br />

and Karlsson (1998), Thorén et al. (1996), Lesica and<br />

Steele (1996), Worley and Harder (1996), Svensson<br />

et al. (1993), Kull and Zobel (1991), Karlsson et al.<br />

(1990), Karlsson 1988), Karlsson and Carlsson (1984),<br />

and Aldenius et al. (1983).<br />

Conservation/management: Several large butterwort<br />

populations are protected on public lands, including<br />

several sites within Isle Royale National Park, and also<br />

via a number of private nature preserves, including<br />

large exemplary areas managed by the <strong>Michigan</strong> Nature<br />

Conservancy in the Straits region. Habitat loss through<br />

shoreline development and recreation is the most<br />

critical threat to butterwort populations, and as for many<br />

coastal areas, the prevalence and widespread use of<br />

off-road-vehicles (ORVs) remains a constant and ever<br />

present threat to sites. Conservation strategies should<br />

focus on the identification and preservation of shoreline<br />

ecosystems that encompass known and potential

habitat. Equally important is the education of private<br />

landowners as well as federal, state, and local land<br />

managers to provide guidance on how to identify and<br />

steward important coastal systems and their associated<br />

rare species.<br />

Comments: The word <strong>Pinguicula</strong> is derived from the<br />

Latin word pinguis, meaning ‘fat’, and refers to the<br />

leaves being ‘greasy’ or ‘buttery’ to the touch. It is<br />

reported that the leaves were once used by farmers to<br />

coagulate milk.<br />

Research needs: The principal need at present, given<br />

the extensive research that has been conducted to<br />

date, is perhaps the identification of viable colonies<br />

and conducting monitoring to determine population<br />

dynamics, trends, changes in status, and the presence of<br />

natural and artificial threats.<br />

Related abstracts: Coastal fen, northern fen, interdunal<br />

wetland, sand and gravel shore, limestone bedrock<br />

lakeshore, limestone cobble shore, volcanic bedrock<br />

lakeshore, cherrystone drop, Eastern massasauga, Hine’s<br />

emerald, incurvate emerald, crested vertigo, six-whorl<br />

vertigo, tapered vertigo, alpine bluegrass, calypso,<br />

English sundew, Franklin’s Phacelia, Hill’s thistle,<br />

Houghton’s goldenrod, prairie Indian plantain, ram’s<br />

head orchid, Richardson’s sedge, rock whitlow-grass,<br />

and numerous additional animal and plant species.<br />

Selected references:<br />

Aldenius, J., B. Carlsson, and S. Karlsson. 1983.<br />

Effects of insect trapping on growth and nutrient<br />

content of <strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong> L. in relation to the<br />

nutrient content of the substrate. New Phytologist<br />

93: 53-59.<br />

Eckstein, R.L. and P.S. Karlsson. 2001. The effect of<br />

reproduction on nitrogen use-efficiency of three<br />

species of the carnivorous genus <strong>Pinguicula</strong>. J.<br />

Ecol. 89: 798-806.<br />

Heide, Fr. 1912. Medd. Om Gronland. 36:441-47.<br />

Kull, K. and M. Zobel. 1991. High species richness in<br />

an Estonian wooded meadow. J. Veg. Sci. 2: 715-<br />

718.<br />

Karlsson, P.S., B.M. Svensson, B.Ǻ, and K.O. Nordell.<br />

1990. Resource investment in reproduction and its<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Features</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong><br />

P.O. Box 30444 - Lansing, MI 48909-7944<br />

Phone: 517-373-1552<br />

butterwort, Page 3<br />

consequences in three <strong>Pinguicula</strong> species. Oikos<br />

59: 393-398.<br />

Karlsson, P.S. 1988. Seasonal patterns of nitrogen,<br />

phosphorous and potassium utilization by three<br />

<strong>Pinguicula</strong> species. Functional Ecology 2: 203-209.<br />

Karlsson, P.S. and B. Carlsson. 1984. Why does<br />

<strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong> L. trap insects? New<br />

Phytologist. 97: 25-30.<br />

Lesica, P. and B.M. Steele. 1996. A method for<br />

monitoring long-term population trends: an<br />

example using rare arctic-alpine plants. Ecological<br />

Applications 6: 879-887.<br />

Lloyd, Francis E. 1942. The Carnivorous Plants.<br />

Chronica Botanica, Waltham.<br />

Méndez, M. and P.S. Karlsson. 2005. Nutrient<br />

stoichiometry in <strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong>: nutrient<br />

availability, plant size, and reproductive status.<br />

Ecology 86: 982-991.<br />

Méndez, M. and P.S. Karlsson. 2004. Betweenpopulation<br />

variation in size-dependent reproduction<br />

and reproductive allocation in <strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong><br />

(Lentibulariaceae) and its environmental correlates.<br />

Oikos 104: 59-70.<br />

Méndez, M., D.G. Jones, and Y. Manetas. 1999.<br />

Enhanced UV-B radiation under field conditions<br />

increases anthocyanin and reduces the risk of<br />

photoinhibition but does not affect growth in<br />

the carnivorous plant <strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong>. New<br />

Phytologist 144: 275-282.<br />

NatureServe. 2006. NatureServe Explorer: an online<br />

encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version<br />

6.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available<br />

http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Accessed:<br />

December 15, 2006).<br />

Slack, A. 1979. The Carnivorous Plants. MIT Press,<br />

Cambridge, MA<br />

Thorén, L.M. and P.S. Karlsson. 1998. Effects of<br />

supplementary feeding on growth and reproduction<br />

of three carnivorous plant species in a subarctic<br />

environment. Journal of Ecology 86: 501-510.

utterwort, Page 4<br />

Thorén, L.M., P.S. Karlsson, and J. Tuomi. 1996.<br />

Somatic cost of reproduction in three carnivorous<br />

<strong>Pinguicula</strong> species. Oikos 76: 427-434.<br />

Svensson, B.M., B.Ǻ. Carlsson, P.S. Karlsson, and<br />

K.O. Nordell. 1993. Comparative long-term<br />

demography of three species of <strong>Pinguicula</strong>. J. Ecol.<br />

81: 635-645.<br />

Voss, E.G. 1996. <strong>Michigan</strong> Flora. Part III. Dicots<br />

(Pyrolaceae-Compositae). Bull. Cranbrook Inst.<br />

Sci. 61 and Univ. of <strong>Michigan</strong> Herbarium. xix +<br />

622 pp.<br />

Worley, A.C. and L.D. Harder. 1999. Consequences<br />

of preformation for dynamic resource allocation<br />

by a carnivorous herb, <strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong><br />

(Lentibulariaceae). Amer. Jour. Bot. 86: 1136-<br />

1145.<br />

Worley, A.C. and L.D. Harder. 1996. Size-dependent<br />

resource allocation and costs of reproduction in<br />

<strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong> (Lentibulariaceae). J. Ecol. 84:<br />

195-206.<br />

Abstract citation:<br />

Penskar, M.R. and J.A. Hansen. 2009. Special Plant<br />

Abstract for <strong>Pinguicula</strong> <strong>vulgaris</strong> (butterwort).<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Features</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong>, Lansing, MI.<br />

4 pp.<br />

Copyright 2009 <strong>Michigan</strong> State University Board of Trustees.<br />

MSU Extension is an affirmative-action, equal-opportunity<br />

organization.<br />

Funding for abstract provided by the <strong>Michigan</strong> Department of<br />

Transportion.<br />

<strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Features</strong> <strong>Inventory</strong><br />

P.O. Box 30444 - Lansing, MI 48909-7944<br />

Phone: 517-373-1552