Lagom is a distinctly Swedish word. Like the now ubiquitous hygge, it doesn’t have a literal English translation, but essentially means “just enough”. It stands for moderation, or not going over the top. It is a defining element of Swedish culture and sums up much about the country, from its understated design and architecture to the conformism of its people. But it’s a concept that was stretched by one of the fathers of Swedish modernism, architect and designer Josef Frank.

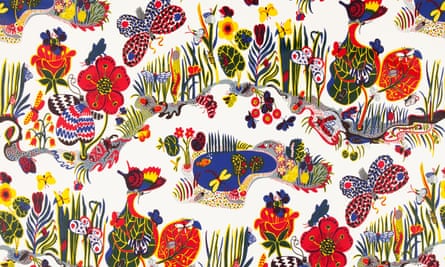

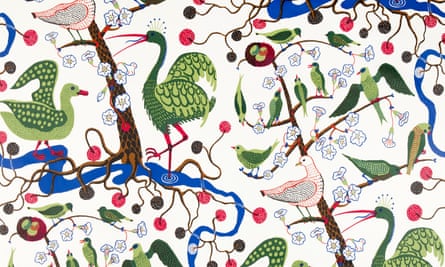

Frank is best known for his vivid textiles for Swedish firm Svenskt Tenn. He created 160 prints for the brand, almost all of them a riotous antitheses of lagom: from vibrant tropical flowers, ferns and insects to oversized leaves in emerald and blue and a now iconic hand-drawn map of Manhattan, where he lived in the early 1940s. He also designed chairs, sofas, lamps, bowls, vases, trays, tables, stool and cabinets.

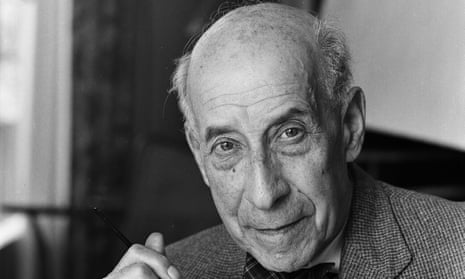

Born in Austria of Jewish heritage, Frank moved to Stockholm with his Swedish wife in 1933, aged 48, to escape growing Nazi discrimination. A committed socialist, he had a successful practice in Vienna, Haus & Garten, where he designed houses, interiors, furniture and fabrics. But when he arrived in Sweden, as an immigrant and a Jew, he couldn’t find work. “It was very difficult for him to get established,” says Svenskt Tenn creative director Thommy Bindefeld. “People didn’t want Jewish immigrants taking their work.” Svenskt Tenn founder Estrid Ericson was the exception: she had created the brand in 1924, with a focus on pewter pieces (“tenn” means pewter), but by the early 1930s her interest had shifted to interiors. Her style was functional and utilitarian, popular in Sweden at the time.

Ericson had long been an admirer, so she asked Frank if he’d consider designing for her brand. His first pieces were opulent and glamorous, using luxurious materials such as brass and velvet, and introducing pattern. “She trusted her eye and her tastes, and didn’t worry too much about what other people thought,” Bindefeld says. “She gave Frank a platform. He would have found life much harder without her, but the opposite is true, too: Svenskt Tenn wouldn’t be here today without him.”

A year after his arrival, the pair took part in a design exhibition for which they created a Hollywood-style room set, with a 2.5m curved sofa upholstered in a floral pattern, an animal-skin rug and a glamorous drinks cabinet. It caused quite a stir. Design historian Hedvig Hedqvist knew Frank when she was an intern at Svenskt Tenn in the 50s. He was, she says, probably thumbing his nose at the restrained Swedish aesthetic. “Unlike Vienna, then the cultural heart of Europe, Stockholm was a bit of a backwater. I think he was teasing the puritanical Swedes a bit.”

Frank believed in creating homes with character, that define the people who live there. His furniture was comfortable, often with rounded edges, and he used colour and pattern to add warmth and personality. Back then, this was a radical idea. “He always put people at the centre of his designs,” says Bindefeld. “Comfort was really important; and he believed you had to soften white walls with prints and pattern to be able to relax in a space.”

Following German annexation of Austria in 1938, Frank found himself stateless. He applied for Swedish citizenship – a process that required two attempts and some high-profile support – then moved to New York for the duration of the war. It proved fertile ground for his textile designs. Some of his most striking patterns emerged during his time there, including the sunflowers and watermelons of his Dixieland print, Italian Dinner with its squid, lobster and tomatoes, and the hand-drawn map of Manhattan that highlighted his favourite streets. In 1944, he sent 50 new designs to Ericson for her 50th birthday.

In 1946, Frank returned to Sweden and continued his collaboration with Svenskt Tenn until his death in 1967. In 1951, they were commissioned by sculptor Carl Milles to design the interior of a newly built house. Called Anne’s house, it was built for his secretary, Anne Hedmark.

Svenskt Tenn still owns all Frank’s designs, and they are made to his original instructions; of the 160 fabrics he created, some 45 are in production at any one time. They are seen as distinctly Scandinavian, their optimistic energy continuing today at Ikea and Marimekko. “Frank brought something to Sweden that we didn’t have,” says Millesgården Museum curator Maria Wiberg. “His work makes you happy.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion