Slime

Stink blog post, 4 January 2021

Image: Fuligo septica, or Dog vomit slime.

Painting from life by William Crowder, 1926.

© National Geographic Society.

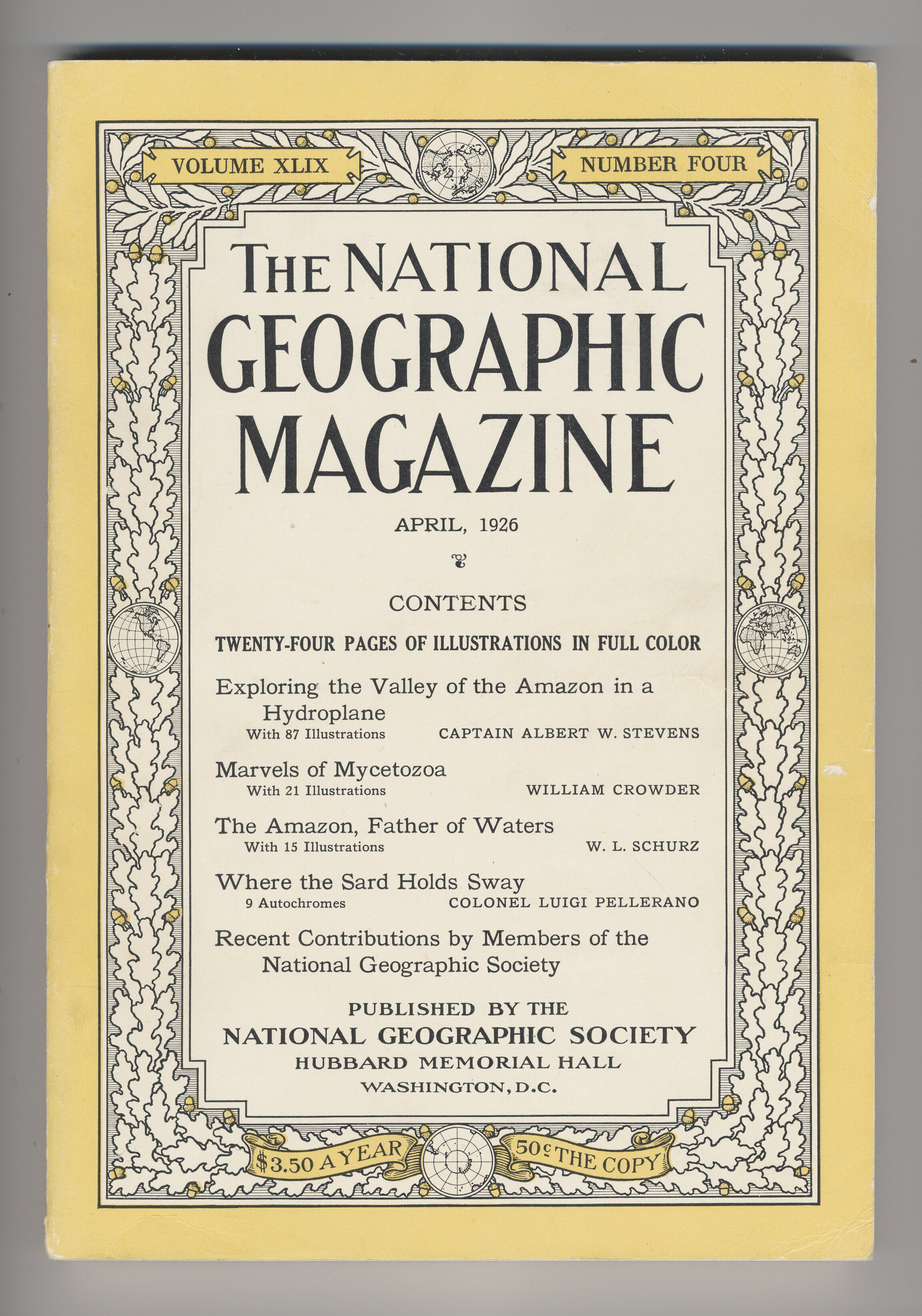

Marvels of Mycetozoa

Fifteen paintings from life of slime mould myxomycetes by marine biologist, naturalist and artist William H. Crowder.

These were first published in The National Geographic magazine, April 1926, alongside an article on ‘the secrets of the Slime Moulds, dwelling on the borderland between the plant and animal kingdoms.'[1]

Under the subtitle ‘In Search of the Oddest Living Things’, Crowder writes that: ‘Although a swamp is a paradise for plants, the sweet Elysium and land of honey for many animals, it is, in the opinion of the average man, a dark and dismal reach — wet, insalubrious, filled even with the miasmatic vapours of death. The region seems not to be the birthplace of vigorous, pulsating life, but a vast and soggy graveyard, a treacherous sink wherein death and disaster are supreme.’[2]

The images below, still under copyright of National Geographic Society until 2022, are all scanned from my own copy of the original 1926 issue of the magazine. They are freely available to buy online as reproduction art prints.

[1] Crowder, William. 'Marvels of Mycetozoa'. In: The National Geographic, April 1926, Vol. XLIX, No. 4. (Washington DC: National Geographic Society, 1926) 421 – 443.

[2] Ibid. 421

Plate I. Leocarpus fragilis [Egg-shell slime mould]. 'The delicate, fungus like organisms known as myxomycetes or mycetozoa are common in all the moist, wooded regions of the earth.' Plate I.

Plate II. Fuligo septica. [Otherwise known as Dog Vomit slime, Scrambled egg slime, or Flowers of tan].

Plate III. Spore case of Badhamia papaveracea. ‘The spore is to the slime mould what the seed is to the higher or flowering plants and the egg to the higher animals.'

Plate IV. Physarum globuliferum.

Plate V. Tirchia persimilis. 'The substance of the plasmodium [the vegetative phase of the slime] resembles the white of an egg in consistency, is slippery to the touch, tasteless and odorless.'

Plate VI. Lamproderma acryrionema.

Plate VII. Stemonitis splendens. [Otherwise known as Chocolate tube slime]. Crowder writes, it ‘has a weird charm and unearthly beauty all its own.’

Plate VIII. Physarum lateritium. In his caption to this colour plate, Crowder comments that slime mould ‘frequently surrounds soft organic substances and completely digests them.'

Plate IX. Diachea leucopoda.

Plate X. Lamproderma violaceum. Crowder is lyrical in his description of this species, writing that it ‘sparkles in the breeze like the waters of an agitated pool in strong sunlight.'

Plate XI. Comatricha pulchella.

Plate XII. Diderma testaceum.

Plate XIII. Dictydium cancellatum. Of the cinnamon-coloured spores that fill the lattice-work baskets of this species’ sporangia, Crowder writes that 'at every lightest breath of air the baskets sway and jostle, strewing their burdens, pepper-box fashion, in all directions.'

Plate XIV. Arcyria ferruginea. 'Groping, streaming, pulsating, the silvery protoplasm of the Arcyria family of slime molds shoots its ghostly threads from moisture-laden logs and wanders over the bark to its place of development into one of the loveliest of natural wonders in miniature.'

Plate XV. Arcyria denudata.

Plate XV. Physarum viride '...suggest eggs and golf balls about to peel.'

Where the Slime Mould Creeps

‘The vast majority of the animal kingdom is composed of single-celled animals, the Protozoa, but as we are not capable of perceiving them without microscopes, we do not “accept” their existence, although we know that we live thanks to them, and that we will end up being eaten and absorbed by them.’

— Vilém Flusser. Vampyroteuthis Infernalis (New York: Atropos Press, 2011) 25.

Micrographs of myxomycete sporangia (the ‘vessels’ in which slime mould spores are produced) reveal wonderfully weird lifeforms in drapes. These are taken from Sarah Lloyd Oam’s book on slime moulds detailing the microorganisms found in the woods near her home in Tasmania.

One of the few modern books on slime moulds, the book features some illuminating time-lapse photography — plus the score for slime mould song, a round, that repeats the words ‘most slimes are not slimy nor do they look like mould’ over a continuous bass singing ‘dog vomit slime, dog vomit slime’.

Sarah Lloyd Oam. Where the Slime Mould Creeps (Birralee, Tasmania: Tympanocryptis Press, 2020) 4, 41.

From top: Cibraria mirabilis, C. cancellata, C. vulgaris and C. microcarpa. All images © Sarah Lloyd Oam, 2020.

Larry Polansky. 'Two slime mould rounds: Eponymy, Empathy'. Grunt, honk, whistle or quack (Birralee, Tasmania : Tympanocryptis Press, 2012).

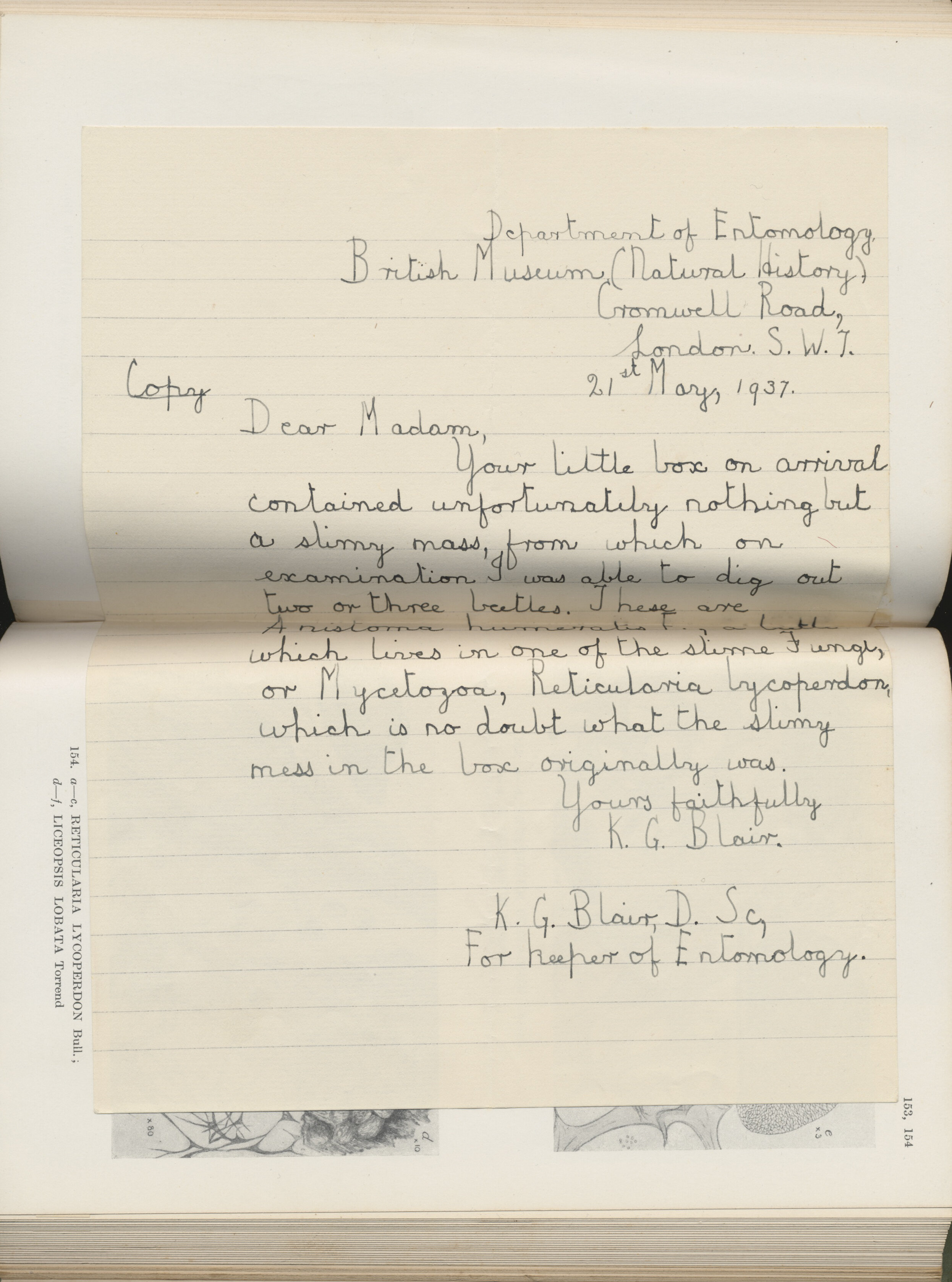

A box of slimy mess

I recently found a letter glued between the pages of an old, secondhand book I bought online. The book was A Monograph of the Mycetozoa by Arthur Lister, a catalogue of slime moulds with illustrations published in 1911. The letter, dated 21st May 1937 and addressed to an unknown woman, was from K.G. Blair, Keeper of Entomology at the Natural History Museum, then a branch of The British Museum.

The letter describes a box containing 'a slimy mass’ presumably sent to Blair in order that he may identify it. He does so by digging out a couple of beetles which he says are commonly found feeding off the slime mould Reticularia lycoperdon, later classified as Enteridium lycoperdon. Blair was a coleopterist, an expert on beetles. The beetles he identifies are Anistoma humeralis, a kind of ‘click beetle’ which commonly lay their eggs in slime moulds. As they hatch, their larvae feed off the spores and help to disperse them.

Letter glued in between pages of Lister’s Mycetozoa adjacent to an illustration of the slime mould Reticularia lycoperdon.

Plate 154: Reticularia lycoperdon; Liceopsis Lobata. In: Lister, Arthur. A Monograph of the Mycetozoa (London: British Museum, 1911).

Enteridium lycoperdon appears as a whitish glob on dead trees or fallen branches later developing a slivery skin which splits to release a cloud of brown, smoke-like spores. The slime mould is more commonly known as the False puffball, and in parts of Mexico, ‘Moon’s excrement’. It has been associated with ‘star jelly’, a strange, translucent, gelatinous substance that emerges miraculously from the earth, sometimes in staggering quantities. Since the fourteenth century, this phenomenon has variously been attributed to the remnants of a fallen star or meteor, or a gooey deposit by some extraterrestrial visitation. A more earthly explanation is that it is the swollen spawn jelly of frogs or toads having been ripped from their ovaries by a predator, though even this has not been fully confirmed.

Blair writes that he is ‘in no doubt… the slimy mess in the box originally was’ Reticularia lycoperdon. For him, the presence of a few dead beetles help confirm this. But could it be that the indistinguishable mess in the box was in fact another kind of slime: amphibian jelly sicked up by a bird, or some other vomitus from the sky?

In any case, it is a rich image: a box full of slime with a few beetles thrown in.

Enteridium lycoperdon in its sporangial stage. Note the resemblance to mollusk eggs. Glentress, October 2020. © Siôn Parkinson, 2020.

‘Star jelly’, Glentress, October 2020. © Siôn Parkinson, 2020.

Stinkhorn slime

‘The stench of death is also the stench of fertilization, of a turning over in the churning teeth of nature.’

— Ben Woodward. Slime Dynamics (Winchester, UK, Zero Books, 2012) 36.

Stinkhorn (Phallus impudicus) in its various stages of growth. Top: Stinkhorn egg, a gelatinous sac showing the tip of the mushroom poised ready to erupt. Middle: Cross-section of stinkhorn egg. Bottom: The ripened mushroom, fallen, yet still intact showing the olive-green, slime-covered glans. All images © Siôn Parkinson, 2020.

— 6 January 2021.

![Plate I. Leocarpus fragilis [Egg-shell slime mould]. 'The delicate, fungus like organisms known as myxomycetes or mycetozoa are common in all the moist, wooded regions of the earth.' Plate I.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f9c25afe1d1ce07c8e953ab/1609859616946-20R61MFUO8Q3CCNJ2Y43/Marvels+of+Mycetozoa+I+CROP.jpg)

![Plate II. Fuligo septica. [Otherwise known as Dog Vomit slime, Scrambled egg slime, or Flowers of tan].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f9c25afe1d1ce07c8e953ab/1609859702794-S0VT8B24M5YUSM53TM01/Marvels+of+Mycetozoa+II+CROP.jpg)

![Plate V. Tirchia persimilis. 'The substance of the plasmodium [the vegetative phase of the slime] resembles the white of an egg in consistency, is slippery to the touch, tasteless and odorless.'](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f9c25afe1d1ce07c8e953ab/1609859869100-PJM9YW9HOXWTA82O5QG5/Marvels+of+Mycetozoa+V+CROP.jpg)

![Plate VII. Stemonitis splendens. [Otherwise known as Chocolate tube slime]. Crowder writes, it ‘has a weird charm and unearthly beauty all its own.’](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f9c25afe1d1ce07c8e953ab/1609859945651-4DFR1SYIVOB0OYOF40C8/Marvels+of+Mycetozoa+VII+CROP.jpg)