The Raphidioptera is a small order of winged, holometabolous insects. Adults (Fig. 1) have an elongate pronotum and two pairs of subequal wings of about 5-20 mm in length. Females have an elongated ovipositor. Larvae (Fig. 2) are terrestrial, living under bark or in detritus, and have biting mouthparts. Pupae are decticous (with articulated mandibles).

FIGURE 1 Female adult of Turcoraphidia acerba (Raphidioptera: Raphidiidae) from Anatolia. Length of forewing 8.5 mm.

Raphidioptera is presumed to be the sister group of Megaloptera + Neuroptera and comprises two families: the Raphidiidae with 200 described species and the Inocelliidae with 25.

The Raphidioptera is distributed throughout the Holarctic region, except for the northern and eastern parts of North America; the southernmost records are from Mexico, northwest Africa, northern India, Indochina, and Taiwan. They are restricted to woodland habitats and occur in almost all Holarctic types of forests and forestlike habitats. In southern parts of their distribution, they live mainly at high altitudes, up to about 3000 m.

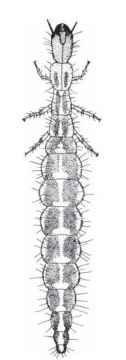

FIGURE 2 Larva of Indianoinocellia mayana (Raphidioptera: Inocelliidae) from Mexico. Length of body 22.5 mm.

HISTORY OF RESEARCH

Snakeflies first appear in the literature in 1735, when Linnaeus described an insect that he called Raphidia. By 1800 only three species had been described; in the 19th century, snakeflies were known from southern Europe, Anatolia, and North America and, by the beginning of the 20th century, also from northern and central Asia and from northern Africa. By 1900, 31 species were known; in 1950, there were 60. At the beginning of the 1960s, a worldwide search for snakeflies and revision of the order was started and more than 150 species were discovered and described between 1960 and 2008. Many species were reared from the egg, so that preimaginal stages and biologies of the majority of species are documented.

CHARACTERIZATION

An extremely flexible head characterizes the adults. It is prognathous, elongate, flat, and strongly sclerotized and may be broad or tapering basally. The large compound eyes are situated laterally. Inocelliidae lack dorsal ocelli. The mouthparts are of the biting type. The prothorax is remarkably elongated, particularly in Raphidiidae, and very mobile (hence the common names snakeflies and camel-neck flies). All three pairs of legs are similar and cursorial. Both pairs of the elongate subequal wings are membraneous, and the venation is simple with few crossveins. The abdomen consists of 10 (visible) segments. Terminal sclerites constituting the external genitalia are extremely complex in males; in females they are equipped with a long ovipositor.

The larvae are elongate and flattened, with a prognathous head, biting mouthparts, and five to seven lateral stemmata. The head and the only moderately elongate prothorax are strongly sclerotized, and the 10-segmented abdomen is of soft consistency.

BIOLOGY

Adult Raphidiidae are day-active entomophagous insects, preying on soft-bodied arthropods and pollen; the natural food of Inocelliidae is virtually unknown, but in captivity they feed on artificial diets and pollen has very rarely been found in their gut. All stages of larvae of both families are entomophagous, feeding on a variety of soft-bodied arthropods; the spectrum of prey is, however, considerably different in bark-inhabiting larvae on one hand and in larvae living in the soil on the other.

There is a long courtship before mating, including a highly sophisticated cleaning behavior with legs and antennae. Two positions of copulation have been observed: a “dragging position” in Raphidiidae, in which the male hangs head first from the female and is carried by her, and a “tandem position” in Inocelliidae, in which the male crawls under the female attaching his head in fixed connection to the fifth sternite of the female. Copulation lasts from a few minutes to 1.5 hours in Raphidiidae, but up to 3 hours in Inocelliidae. Spermatophores have been observed and studied only in Raphidiidae.

The egg stage lasts a few days to 3 weeks. The number of instars varies around 10 to 11 and may reach 15 or more. The larval period lasts 1 year in a few species, in most species it is 2 or 3 years, and under experimental conditions it may be up to 6 years. The prepupal stage lasts a few days. In the majority of species, pupation takes place in spring and lasts a few days to 3 weeks. In some species pupation starts in summer or autumn and the pupal stage lasts several (up to 10) months; in a few others pupation starts in summer and adults hatch in late summer after a short pupal stage. Hibernation thus usually takes place in the last larval stage, the penultimate stage, or the pupa, but never as eggs, prepupae, or adults. The pharate adult (the active pupa) is very mobile.

Snakeflies need a period of lowered temperature (usually around >0°C) to induce pupation or hatching of the imago. Larvae that are continuously kept at room temperature will usually not pupate but become prothetelous, i.e., they develop pupal or imaginal characters, such as compound eyes, wingpads, and appendages on the abdomen, and may live for years.

Parasites, parasitoids, and hyperparasites are a frequent phenomenon among Raphidioptera. Hymenoptera are of considerable significance as parasitoids of larvae, and species of the genus Nemeritis (Ichneumonidae) comprise 90-95% of them; other ichneumonids, braconids, and chalcidids contribute about 1%.

Snakeflies are effective predators; all larval stages of all species of both families, and at least the adults of Raphidiidae, feed on (mainly soft-bodied) arthropods. Snakeflies are believed to be rare insects. This is true for many species and many regions, but a number of species often occur in large numbers. There have been several attempts to use snakeflies as biological control agents: an unidentified North American species was introduced in Australia and New Zealand 100 years ago, but did not become established. The use of snakeflies for future biological control efforts is, however, hampered by the long developmental period and narrow food preference of these insects.

DISTRIBUTION AND BIOGEOGRAPHY

Extant Raphidioptera are confined to the Northern Hemisphere and almost exclusively to the Holarctic region. In Central America the southernmost records are from high altitudes at the Mexican-Guatemalan border. In Africa snakeflies have been found only in arboreal regions north of the Sahara, and in Asia the southernmost records are from altitudes above 900 m in transition areas from the Palaearctic to the Oriental region in northern India, Myanmar, and northern Thailand. The northern and eastern parts of North America lack snakeflies. Almost all species are restricted to very limited areas of a refugial nature. Only three species represent a Eurosiberian type of distribution occurring throughout northern Asia to central and northern Europe, and a few Nearctic species with distribution centers in the southwest have reached Canada.

SYSTEMATICS, TAXONOMY, AND FOSSILS

The order Raphidioptera is a relic group of “living fossils” that comprises two extant families and 225 described species.

Taxonomy of adults has been well established. Because shape and coloration of body structures and of wing venation are highly variable, the most powerful and reliable tool is the morphology of the genital sclerites, in particular of the males. Taxonomy of larvae, mainly based on patterns and coloration of the abdomen, still remains difficult because of the similarity of related species.

The fossils lead to the conclusion that there was an enormous biodiversity of Raphidioptera in the Mesozoic. The majority of species and genera (in several families) are known from Jurassic and Cretaceous deposits. The rich and diverse Raphidioptera fauna of the Mesozoic died out at the end of the Cretaceous, probably due to the K/T event (that is the worldwide catastrophe resulting from an asteroid of about 10 km diameter that hit our planet) 65 mya ago and its climatic consequences. In particular, all snakeflies of tropical climates disappeared and apparently only the few representatives adapted to a cold climate survived. Fossil snakeflies from Tertiary layers, as well as from Baltic amber, belong to the two extant families.