One of the commoner mosses in Sussex and readily found once you know both its habitat and what it looks like. It is likely to be in many gardens for example. It is well worth studying in detail since you will learn a lot about the genus in doing so.

A typical habitat would be on paving, either in the cracks between slabs or on the side of a step as in the photograph but it needs to be shaded for much of the day as the plant tends to avoid very open positions.

It usually forms small cushions (but can occasionally get bigger), often with slightly paler ends to the shoots that can give it a starry appearance from a small distance. When dry, the shoots crisp a little:

They don’t crisp right up like D. insulanus nor are they just appressed like D. luridus. When moist, the shoots open right up and the leaves curve away from the stem.

The moist shoot has similarities to D. fallax but the leaves look stiffer towards the tip and the habitat would be generally unsuitable for that species which prefers more open spots on chalk or gravel. The leaves are noticeably narrowed at the tip which is often brownish:

The laminal cells don’t reach the apex of the leaf but stop a short distance below so that the very tip of the leaf is composed entirely of the nerve. The upper margins of the leaf are bistratose too which, together with the excurrent nerve, provides considerable stiffness to the upper leaf and probably gives rise to the scientific name too:

In common with most members of the genus, the leaf cells can be very papillose. Below the apex, the leaf margins are recurved.

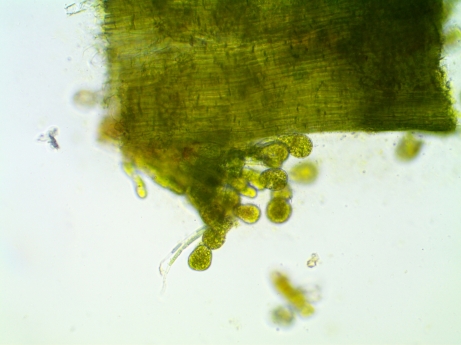

The leaves have gemmae in their axils (leaves removed from a section of stem):

The gemmae are carried on short filaments but soon detach. Occasionally they can get so numerous as to be visible with a hand-lens but usually there is too much dirt collected in the axils to make that possible.

In the field, you can tell its probably a Didymodon by the gradually narrowing leaves with recurved margins and papillose cells that aren’t obviously translucent. The short, often brownish, rigid leaf apex composed entirely of nerve is often enough then to identify it. D. luridus has shorter leaves, more triangular and more concave at the base.

Bryoerythrophyllum recurvirostrum leaves can look very similar to several Didymodon species but it has a change of taper near the leaf apex that is characteristic although subtle until understood. The lower parts of shoots are often brick-red in colour. It can certainly grow in similar habitats to D. rigidulus. The best distinction is provided by the thin-walled, hyaline, basal cells that are quite different to the often undifferentiated basal cells of Didymodon.

The really similar one in the same habitat is D. nicholsonii which is generally larger with wider leaves and usually with a hooded leaf apex but note that this latter character may be missing in some populations. The upper leaf margins are also bistratose. In such cases you have to resort to cell size to be reasonably certain as D. nicholsonii has smaller cells (6 – 8µm) than D. rigidulus (8 – 10 µm). In drier habitats such as chalk downs it would be advisable to check for D. acutus as that too has a (usually longer) excurrent nerve.

D. fallax, apart from growing in much drier habitats, is usually a browner plant and the leaves curve away from the stem more consistently when moist. The major difference is the cells on the top surface of the nerve in the upper 1/3 of the leaf (variously called ventral cells or adaxial cells). These are the exposed surface of the nerve itself and are elongate. In most other common members of the genus, the laminal cells of Didymodon rigidulus extend over the nerve which thus appears to have short, rounded-quadrate, papillose cells.

Pingback: Basic bryology | Sussex Bryophytes