Mention silk and most people will, I guess, immediately think of spiders and cobwebs.

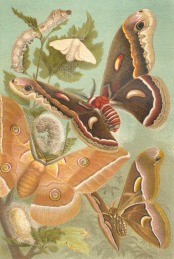

Pressed a bit further, some may mention silkworms, and some might even know the word sericulture and that the common silkworm feeds on mulberry bushes. What they may not know, is that the silk worm is the larvae of the moth Bombyx mori and that there are actually four species of lepidopteran larvae commonly used in silk production. These are pictured below in the lovely illustration from Meyers Konversations-Lexikon; next to the picture are some B. mori larvae.

Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 4th Auflage, Band 14, Seite 826a (4th ed., Vol. 14, p.826a)

Four of the most important domesticated silk moths. Top to bottom: Bombyx mori, Hyalophora cecropia, Antheraea pernyi, Samia cynthia. From Meyers Konversations-Lexikon (1885-1892

Silk production is of course not just a feature of spiders and lepidoptera. It is a widespread feature of insect life, being used for pupal cases, as a mode of transport (ballooning) as shown by larvae of the gypsy moth and other species of Lepidoptera,

protective cases as in larval caddis flies or also, by some caddis fly larvae, as fishing equipment.

But in my opinion, the most dramatic use of silk is that seen in a genus of micro-moths, belonging to the Yponomeutidae, the small ermine moths, Yponomeuta. They and their relatives, are silk-producers extraordinaire. Collectively, they are known as small ermine moths; so called because of their adult colouration which resembles the ermine worn by nobility and small, because of the existence of several larger moths with ermine in their names.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yponomeuta_evonymella-02_(xndr).jpg#file

The larvae are less attractive and are the web/silk producers.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yponomeuta.evonymella.caterpillars.jpg

My particular favourite is the bird cherry ermine moth, and not just because the bird cherry is my favourite tree. (My eldest son’s middle name is bird cherry, albeit in Finnish). The adult moths lay their eggs in August, in clusters of up to 100 or so on young twigs of the bird cherry Prunus padus, cover them with an egg shield and then die (Leather, 1986). The eggs hatch shortly afterwards and the larvae spend the winter under the egg shield until the following spring. When the buds begin to burst in spring, the larvae emerge from beneath the shield and begin to feed gregariously on the newly emerging leaves, spinning a web that protects them from natural enemies and may also help in thermoregulation and as a trail indicator (Kalkowski, 1958) http://edepot.wur.nl/201846 . It is possible to have great fun by selecting a lead larvae to act as a trail blazer and watch the rest of the colony follow them to a destination you have chosen.

Every three to four years or so, populations of the moths get so high that they exhaust their food supplies, defoliating entire trees and covering them with a tough coating of silky white webbing (Leather, 1986; Leather & Mackenzie, 1994). In fact, in Finland, I once saw three neighbouring trees totally enveloped in a silken tent caused by the bird cherry ermine moth, Yponomeuta evonymellus, that you could enter and shelter inside from the rain. Once they really get going as spring progresses, the landscape, particularly if in an area where bird cherry is common, begins to take on a somewhat wintry look, which for May is a little odd. Those of who you, who have travelled north of Perth in Scotland, on the A9, will be familiar with this phenomenon. It frequently makes the Scottish newspapers and generates headlines such as “winter wonderland” or “ghostly landscape”. As they run out of trees, the larvae begin to migrate in a desperate search for trees with leaves still on them, and by now, have become less fussy about what they eat. It is at this wandering stage of their life that the true extent

of their singlemindedness (I have seen a trail of thousands of larvae marching along a railway line; they didn’t survive the passing of the 0850 from Helsinki) and their ability to produce silk becomes startlingly apparent.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ermine_moth_larva_on_a_Swedish_army_bike.jpg

Truly, silk is not just a spider thing.

Kalkowski, W. (1958). Investigations on territorial orientation during ontogenic development in Hyponomeuta. Folia Biol Krakow 6: 79-102.

Leather, S. R. & Mackenzie, G. A. (1994). Factors affecting the population development of the bird cherry ermine moth, Yponomeuta evonymella L. The Entomologist 113: 86-105.

Leather, S. R. (1986). Insects on bird cherry I The bird cherry ermine moth, Yponomeuta evonymellus(L.). Entomologist’s Gazette 37: 209-213.

Love the pictures of what Yponomeuta can do.

LikeLike

Pingback: Silk – not just a spider thing | Science Communication Blog Network

Pingback: The Week In Science (March 4 – 10) | Science Communication Blog Network

Pingback: Sloth Moths – moving faster than their hosts | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Wow!! I didn’t know anything about these moths.

LikeLike

They are fantastic

LikeLike

Pingback: A rose by any other name – In praise of the Rosaceae | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: Planes, trains and automobiles – insect killers? | Don't Forget the Roundabouts