Bedfordia salicina is a Tasmanian endemic understorey tree belonging to the Asteraceae (daisy) family. It is common in wet eucalypt forests where it attains a height of between 2 and 5 meters. It has fissured, flaky absorbent bark and is often rich in slime moulds so I regularly check the numerous standing and fallen dead trees on my study site.

On 1 October 2017 I closely inspected the log. It had several well-developed mosses and was strongly decayed in the lower part suggesting it fell some time ago.

On 30 September 2017 a patch of pure white sporangia on the underside a small slightly elevated the log first caught my eye. By the following day the sporangia had changed colour from white to a pale pink characteristic of a developing Arcyria sp. By 9 October the capillitium had completely fallen away from the calyculus and had formed a long plume, a characteristic of Arcyria affinis. ( A. denudata is scarlet or carmine red when it first appears. It has a capillitium that both retains its shape, and remains attached to the calyculus.)

I collected a few fruiting bodies on 4 October to photograph at home (with a Canon EOS 70D camera mounted on the stereo microscope) and noticed that the peridia had an unusual appearance, probably because they had experienced rain while developing. Later the same day I took another photograph of the sporangia with expanding capillitium. The dark spots on the apex of the sporangia are possibly another indication that the developing sporangia had experienced some wet weather.

Once I’d noticed the developing Arcyria and the other species on the log, I protected them from the next bout of rain with an old umbrella – an ideal thing in such situations although the shadier than normal conditions may affect developing sporangia.

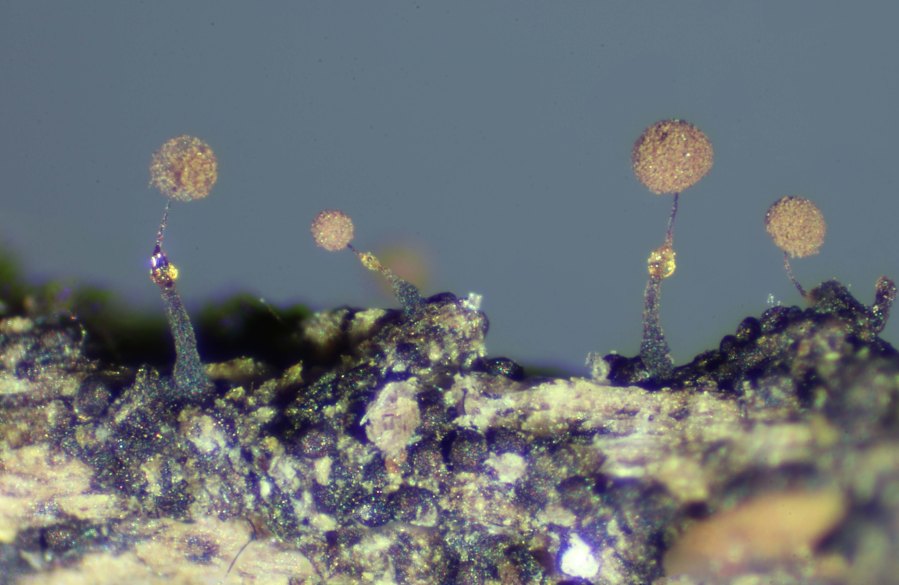

When I downloaded the photograph of the Arcyria taken on 1 October 2017, I noticed some white spherical 0.2 mm diameter dots of newly emerged sporangia of Clastoderma debaryanum. By 3 October 2017 larger groups of this tiny species started to appear on the log. I collected one to photograph at home and noticed that I’d also collected one fruiting body of Cribraria microcarpa, bringing the number of species on the log to seven—and all within one metre of each other.

There was also a small group of sporangia that were initially yellow and later brown. According to Nannenga- Bremekamp (1991), the plasmodia of T. decipiens is “white (or pink or orange)” and in the notes about T. decipiens var. olivacea, the plasmodium is described as pink.

The upper surface of the log also had small groups and scatterings of bright orange ‘beads’ of Trichia decipiens var. olivcea. The orange beads gradually went dark brown, then, as the fruiting bodies, spores and elaters dried out, they changed to olivaceous brown.

Scattered among the sporangia of the different species were numerous fruiting bodies of Clastoderma debaryanum.

Also on 1 October 2017 were three clusters of white ‘beads’ on the upper surface of the log. By the following day they had elongated and changed shape and colour (from white to rusty red) characteristic of Stemonitis axifera.

Other identifying features of this common Stemonitis is the columella that gradually tapers towards the apex of the sporangium and is wavy in the upper part where it gradually merges into the capillitium. The internal net has about 3 meshes over the radius and the surface net has angular meshes with some free ends.

On the underside of the log on 4 Oct. 2017 were several small clusters of yellow sessile sporangia of Trichia affinis. The sporangia changed from tan brown to yellow as the fruiting bodies dried out and the capillitium (i.e. elaters) started breaking through the delicate peridium. The yellow elaters have spiral bands connected by longitudinal striae and free ends with short points. The spores have a broken reticulum.

Also on the log on 4 October were numerous pale yellow sporangia above the Arcyria affinus (see photo below). They looked whiter later in the day but gradually darkened—more Trichia decipiens. Interestingly, over the past seven years the Trichia decipiens with bright orange or pink plasmodia have been much more common than the varieties with a white or pale lemon plasmodia.

On 10 October I collected what I thought was a group of C. debaryanum as I wanted to calculate the number of sporangia on the log. On close inspection, the tiny sporangia turned out to be more Cribraria cf. microcarpa.

Within the colony of the Cribraria microcarpa was one fully developed sporangium of Physarum viride, bringing the total number of species on the log to eight.

This concentration of several different species on a particular substrate is not unusual. In fact, I have observed this so often that if I find one species on a log, I usually check the rest of the log for either the same species at different stages of development or several different species as in the case of the Bedfordia log.

The location of the forest ‘hotspot’ varies from year to year. During the previous several years, a standing dead Bedfordia slightly upslope from the current log under observation was productive for several years. Like the current log, most of the species were Trichiales including Trichia decipiens (I observed white, yellow, orange and hot pink ‘beads’) and extensive colonies of Metatrichia floriformis that formed over two consecutive years. Stemonitopsis typhoides also appeared.

Five years ago a multi-stemmed Bedfordia with three small leaning trunks only meters from the current log were productive with numerous Physarum viride, Arcyria riparia and more! One of only 4 samples I have of Willkommlangea reticulata was collected from one of the trunks.

The amount of activity inside a log from which are emerging eight different species almost simultaneously is interesting to ponder. Members of the order Stemonitidales have aphanoplasmodia that feed within the log and come to the surface to form sporangia; the same is believed to be the case for the Trichiales. In contrast, Clastoderma debaryanum arise from protoplasmodia from which come one or two fruiting bodies; protoplasmodia are typical of species with minute fruiting bodies.

According to Madelin (1984)

“The protoplasmodium of Clastoderma debaryanum when first formed in culture also feeds on bacteria, but as it grows bigger it begins to ingest its own spores, myxamoebae and cysts.”

In his introductory chapter to The North American Slime Moulds (1899), Thomas Macbride states:

“… the plasmodia follow moisture … especially to follow nutritive substrata. They seem also to secure in some way exclusive possession. I have never seen them interfered with by hyphae or enemies of any sort, nor do they seem to interfere with one another. Plasmodia of two common species Hemiarcyria clavata and H. rubiformis, are often side by side on the same substratum, but do not mix, and their perfected fruits presently stand erect side by side, each with its own characteristics, entirely unaffected by the presence of each other. On the other hand, it is probable that some of the forms which … are to us distinct, may be more closely related than we suspect, and puzzling phases which show the distinctive marks supposed to characterize different species are no doubt sometimes to be explained on the theory of plasmodial crossing; they are hybrids.”

References:

Macbride, T.H., (1899) North American Slime Moulds. Macmillan, New York, NY.

Madelin, M.F., (1984) ‘Presidential address Myxomycete data of ecological significance.’ Trans. Br. Myco. Soc. 83 (1), 1-19 (1984).

Nannenga-Bremekamp, N.E., (1991) A guide to temperate Myxomycetes. Biopress Ltd, Bristol, England.