Until a day or two ago, it was feeling quite springy around here – longer days, mild daytime temperatures, and I’d begun the flurry of client interviews and site assessments that typify my spring schedule. Then BAM – old man winter returns with a big dump of the white stuff. Lucky for you, this means a short reprieve from aforementioned activities, and I can work on this post. Next in the plant form series is weeping form.

Weeping Form

Weeping plants can be huge trees like Betula pendula ‘Laciniata’, or small grafted specimens like Betula pendula ‘Youngii’. The large weeping trees have less distinct form because there are countless branches, each with delicate drape – the resultant outline of form is therefore somewhat amorphous, though still quite elegant.

Large weeping trees like this weeping birch don’t exhibit a distinct outline – the weeping habit of their branches creates more textural interest, than well-defined form. Photo: Pat Gaviller

To me, they bring a sense of quiet luxuriance to a landscape, perhaps because I associate this form with the giant weeping willows that reside near still waters – the picture of both opulence and serenity.

Although these big weepers lack definitive form, their lacy texture makes them lovely feature trees – if scale and proportion allow. They are especially lovely as waterside accents and make elegant shade trees – again if the size of your house and/or property allows.

Small weeping trees offer much stronger architectural form than their larger counterparts– their arched weeping branches create an umbrella-like form. Many of the weeping specimens available at nurseries are actually low-growing creeping shrubs that have been grafted onto a standard, for example Young’s weeping birch, Walker’s weeping Caragana or Rosy Glo weeping crabapple.

This form draws the eye up … and back down again. It is strongly dominant so should always be used as a single specimen – I can’t stress this enough. Don’t try to group them in threes, or use two to frame an entry, or plant several in linear fashion – it just doesn’t work. I made the mistake of planting two in my front yard several years ago – you can read about it in my post from last year around this time: Form, Colour and Texture in the Winter Garden. The bottom line is, any more than one and they’ll just compete for dominance and create visual unrest. So one is enough – got it?

Malus ‘Rosy Glo’ makes a beautiful specimen tree as it looks spectacular any time of year – here I’ve underplanted with Juniperus sabina ‘Moor Dense’ which stages her nicely. Photos: Sue Gaviller

A weeping form makes a nice centrepiece for a symmetrical composition. Left – Caragana arborescens ‘Walker’s Weeping’ in a client’s raised planter. Right – another of those pretty scenes I periodically drive by, C. arborescens ‘Walker’s Weeping’ in winter still has strong form. Photos: Sue Gaviller

Walker’s weeping Caragana: simple repetition of line makes this tidy scene one I often stop to admire. Photo: Sue Gaviller

These small weeping trees are useful for highlighting architectural details, like arched doorways or windows – the arching form of the branches mimic the architectural line, thus bringing attention to it, and creating unity (by repetition).

Fountains too, can be ‘echoed’ in this way with the placement of a weeping tree nearby.

As well, a weeping form looks very appealing at the top of, or near a slope – the weeping branches reiterate the sloping line of the hillside.

And don’t plant one of these feature trees in the middle of an expanse of lawn where it will appear lonely and insignificant – it’s much more effective when staged and supported by the presence of other plant material.

A fine-looking specimen, Picea abies ‘Pendula’ looks splendid in this sloped front yard garden in charming Elora, Ontario. Photo: Sue Gaviller

I’ve had several clients tell me they don’t like the shape of weeping trees because it makes them feel sad (maybe it’s the name – y’know power of suggestion and all). I don’t get this. To me weeping forms are graceful and very pleasing to the eye. Indeed their appropriate use demonstrates a mature design sensibility. I guess it’s a humble reminder for me, and all you aspiring designers, that there is a degree of subjectivity in design that must be acknowledged and respected. And with that little piece of wisdom my friends, I shall bid you adieu.

More “Fun with Forms” in my next post – see ya then.

Humbly yours, SueRelated articles

- The Form of Things to Come – Part 2 (notanothergardeningblog.com)

© Sue Gaviller and Not Another Gardening Blog 2012.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sue Gaviller and Not Another Gardening Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

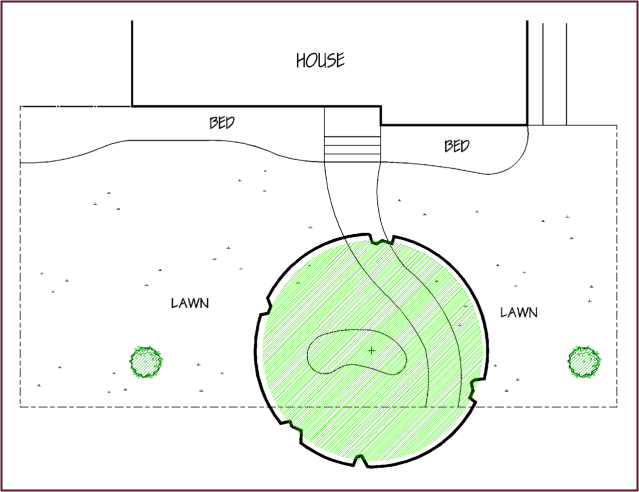

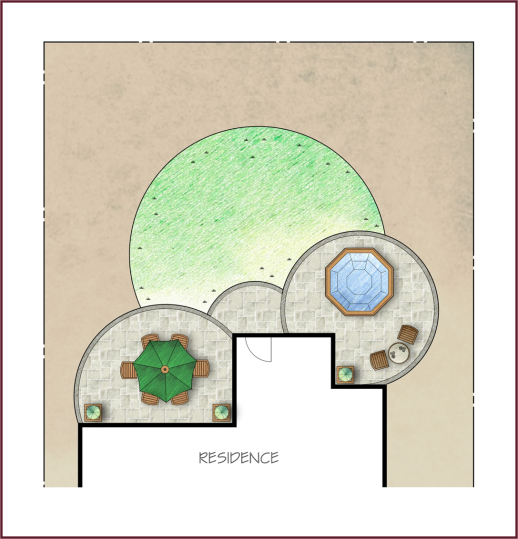

In addition each rectangle is in itself proportioned such that the shorter dimension is two-thirds the length of the longer one. The result is a design with very pleasing proportions.

In addition each rectangle is in itself proportioned such that the shorter dimension is two-thirds the length of the longer one. The result is a design with very pleasing proportions.

In the examples to the left, the top image illustrates a house that is visually overwhelmed by the landscaping – the shrubs next to the house are as tall, or taller than the house, with some even obscuring windows. And the shade trees are huge in relation to the house – this scale is too large. The middle example is the exact opposite. The trees and shrubs look like toys in comparison to the house – the scale of this landscape is too small. The bottom example is what we’re after. The landscape elements are well suited to the size of the house, hence this represents appropriate scale.

In the examples to the left, the top image illustrates a house that is visually overwhelmed by the landscaping – the shrubs next to the house are as tall, or taller than the house, with some even obscuring windows. And the shade trees are huge in relation to the house – this scale is too large. The middle example is the exact opposite. The trees and shrubs look like toys in comparison to the house – the scale of this landscape is too small. The bottom example is what we’re after. The landscape elements are well suited to the size of the house, hence this represents appropriate scale.

The other thing that happens is illustrated on the left. In the top example, the diorama represents an older home with plantings typical of the time it was built – Cotoneaster hedge, Potentilla, and little Johnny’s ‘Arbour Day’ tree, a Colorado spruce (Picea pungens). Not particularly inspired I realize, but at least it’s in scale with the house. Fast forward a few decades and the scenario depicted in the bottom photo has likely ensued. Little Johnny is forty years old now and so is this landscape. I guess nobody took into account way back when, that living things don’t remain static. They grow … and grow and grow. So what was once in scale is no longer.

The other thing that happens is illustrated on the left. In the top example, the diorama represents an older home with plantings typical of the time it was built – Cotoneaster hedge, Potentilla, and little Johnny’s ‘Arbour Day’ tree, a Colorado spruce (Picea pungens). Not particularly inspired I realize, but at least it’s in scale with the house. Fast forward a few decades and the scenario depicted in the bottom photo has likely ensued. Little Johnny is forty years old now and so is this landscape. I guess nobody took into account way back when, that living things don’t remain static. They grow … and grow and grow. So what was once in scale is no longer.