Since violets don’t usually bloom here until the end of April, I was surprised to find them so early. I was doubly surprised to see that they were white wood violets (Viola sororia albiflora) because I see maybe one white one for every hundred blue / purple ones. I’ve read that the American Violet Society says that the white ones are just white versions of the common blue violet (Viola sororia.) A kind of natural hybrid, I suppose. They’re prettier in my opinion, with their dark guide lines that help insects find the prize.

That ancient plant the Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas) has bloomed. They are members of the dogwood family but you would never know it by the tiny flowers, each one about an eighth of an inch across. The entire flower cluster seen here is barely an inch across. Though I’ve never seen it they say that each flower will become a small red fruit.

It is the fruit of the Cornelian cherry that is the reason it has been used since ancient times. Man has had a relationship with this now little-known shrub for about 7000 years, and we know that from finding remains of meals from the early Neolithic period that included cornelian cherry fruit. They usually bloom at about the same time Forsythias do, but they are seen in the form of small trees rather than the shrubby form of Forsythias. From a distance it might be easy to mistake one for a dwarf crab apple when it wasn’t in bloom.

So far, I’ve seen just two magnolia blossoms, this one and a white one that had been nipped by frost. So far it seems like spring is moving very slowly because of the still cool nights. Days are running in the high 50s F. lately and showery to partly sunny for the most part.

Hyacinths have come along now, and they always seem to me to mark the midway point of the flowering bulb season. They’re very beautiful and one of the most fragrant of all the spring flowering bulbs.

All of the sudden there are daffodils everywhere. In the last flower post I did I showed some that had been hurt by frost but these were untouched. According to the National Trust in the U.K. the daffodil’s drooping flowers are said to recall the story of Narcissus bending over to catch his image in a pool of water.

The local college has some very early tulips. They stay small but after a while will have yellow along with the red in the blossoms, if I remember correctly.

Striped squill (Puschkinia scilloides, var. libanotica.) is a scilla size flower that is one of my very favorite spring flowering bulbs. I tried to find them years ago and had a hard time of it but I just looked again and they now can be easily found through most spring bulb catalogs. Still, even though they’re easy to find now I never see them. I know of only this one place to find them and they are very old, coming up in the lawn of a local park. Though the catalogs will tell you that the blue stripes are found only on the inside of the blossom they actually go through each petal and show on the outside as well. I think they’re very beautiful.

Johnny jump ups (Viola) are blooming by the hundreds now. I chose this as my favorite on this day.

The cool weather is being good to the coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara) plants. I see more and more blossoms but not a single seed head yet.

This dandelion blossom was just waking up, and I put it here so those of you who don’t know could see the difference between it and the coltsfoot blossom in the previous photo. In truth the only thing they have in common is the color. Size, shape and growth habit are different but the easiest way to tell the two apart is to look at the flower’s stem. Coltsfoot stems are scaly and dandelion stems are smooth.

Bleeding hearts (Dicentra spectabilis) are growing about an inch per day when the sun shines, and if you look closely, you can see tiny flower buds all ready to get started. These are the tall, old fashioned bleeding hearts that die back in the heat of summer.

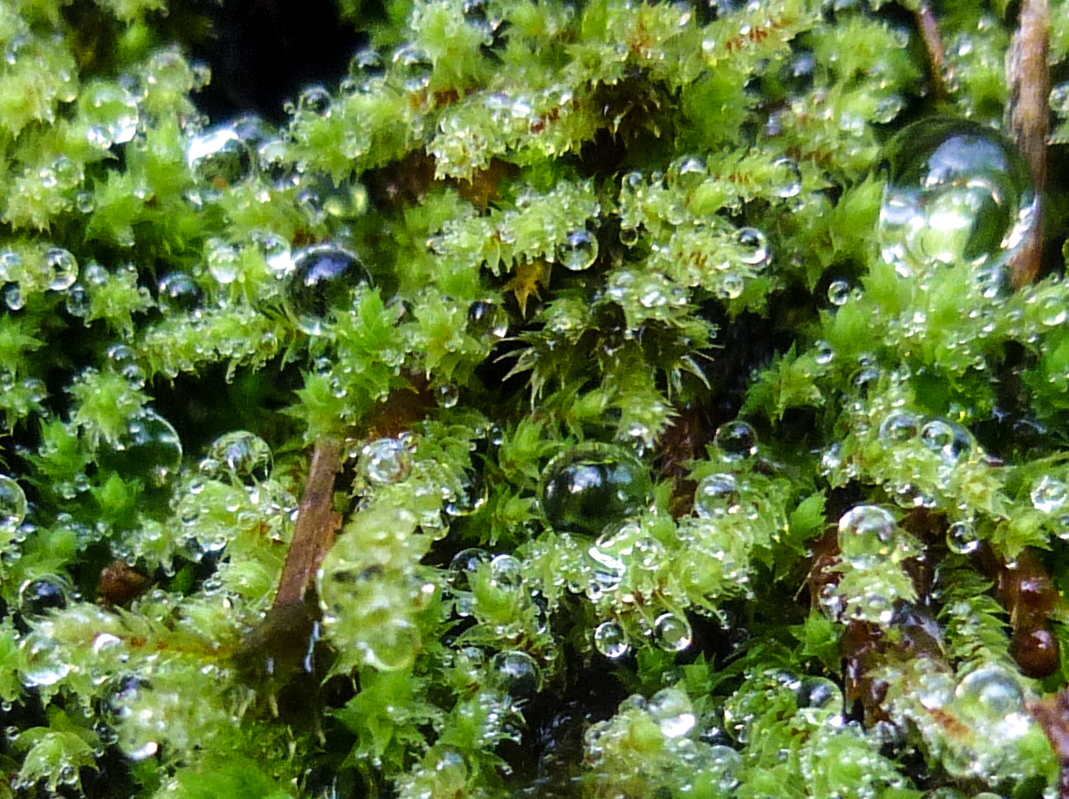

Raindrops were being cradled lovingly by the new growth.

Skunk cabbages (Symplocarpus foetidus) are looking more cabbage like each day, but you wouldn’t want to eat them.

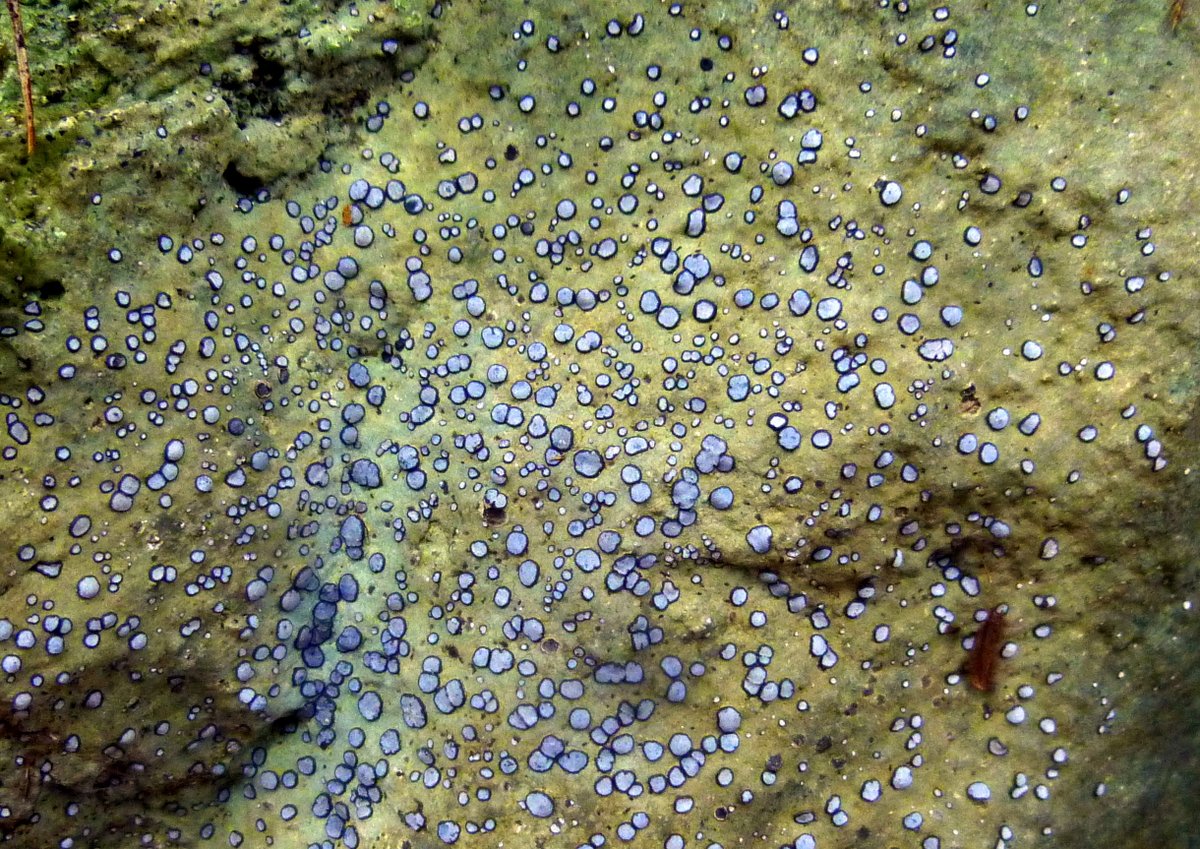

I’ve been looking for some moss spore capsules to try out my new camera on and apple moss (Bartramia pomiformis) obliged with its tiny round capsules, fresh out for spring. Reproduction actually begins in the late fall for this moss and immature spore capsules (sporophytes) appear by late winter. When the warmer rains of spring arrive the straight, toothpick like sporophytes swell at their tips and form tiny green globes, so their appearance is a good sign of spring.

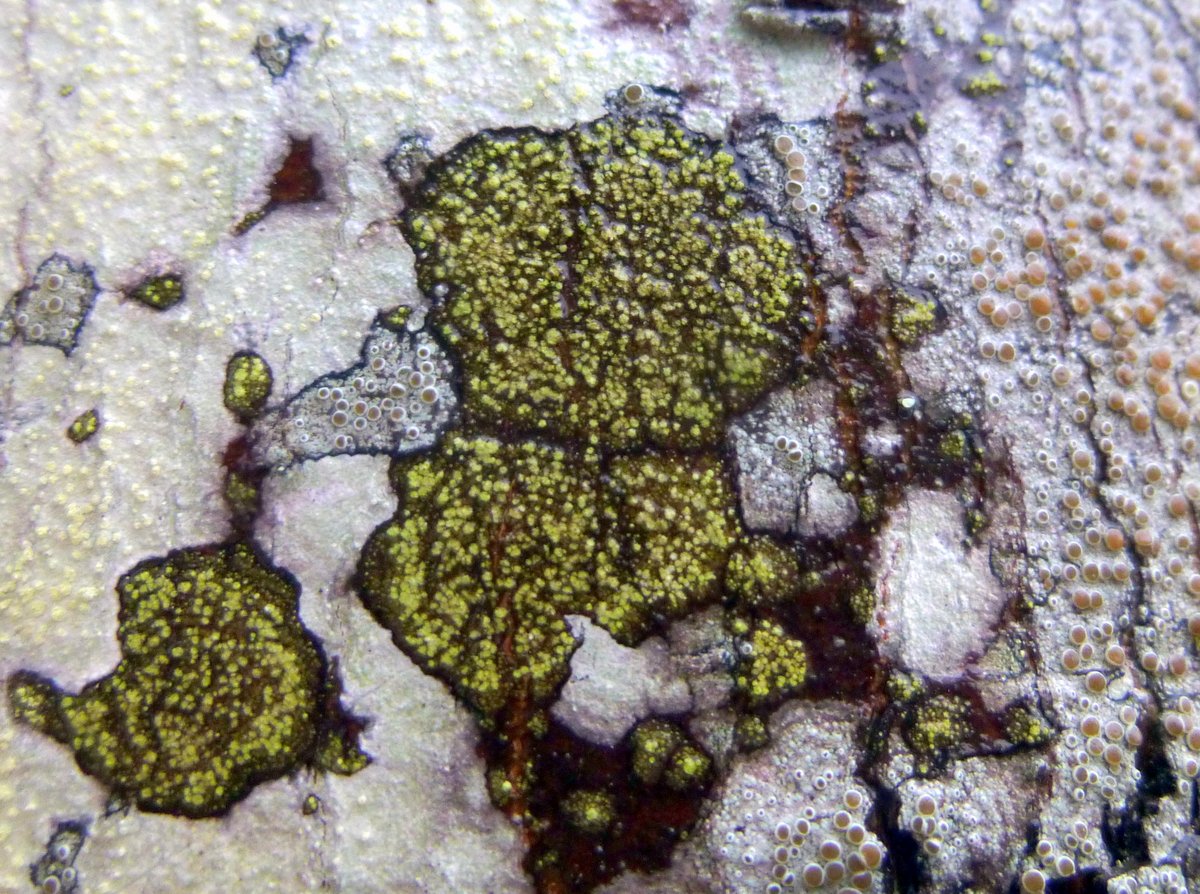

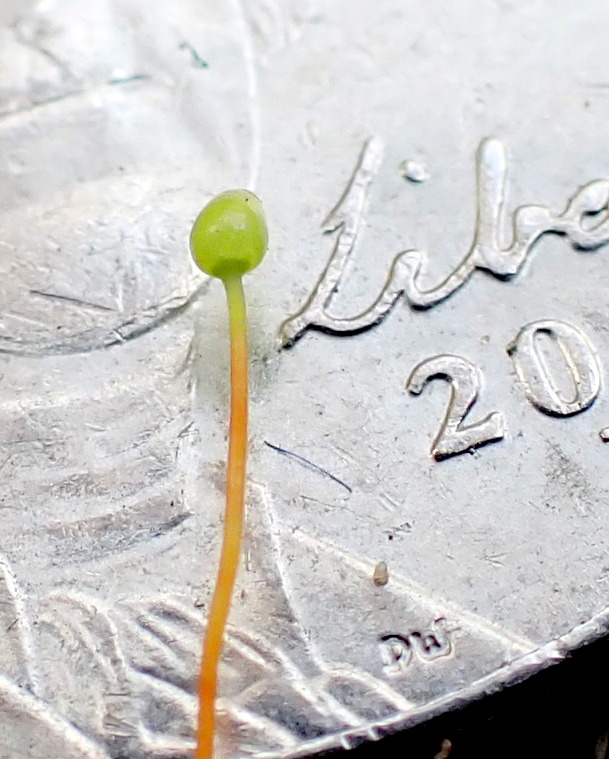

Each spore capsule is about 1/16 of an inch in diameter. Tiny, but after a few failed tries the new camera was able to do the job. The pointed part seen is the calyptra, which is a hood or cap which covers the lid-like operculum. The calyptra falls off first as time passes and the spores ripen, and finally when the spores are mature the operculum comes off and the spores are released to the wind.

Here is an apple moss spore capsule against a U.S. nickel. I tried to find the height of the date text on a nickel but had no luck. It is safe to say that it’s very small.

Though the male catkins are looking a bit tired the female flowers of American Hazelnuts (Corylus americana) are still going strong.

Hobblebush buds (Viburnum lantanoides) are opening but you’d never know it unless you had watched the hard mass that was there in winter slowly soften and begin to expand. Still, even at this stage it isn’t much to look at, and it might be hard to believe that in about a month it will be one of our most beautiful native wildflowers.

It is indeed hard to believe that the unshapen mass in the previous photo will become something as beautiful as this, but come mid May the woods will be full of wonderful blossoms like this one. Hobblebush flower heads are large-often 6 or more inches across, and are made up of small, fertile flowers in the center and larger, sterile flowers around the outer edge. All are pure white. I can’t think of a better reason to walk through the woods in spring.

I haven’t seen any of the feathery female flowers of the elms (Ulmus americana) yet but I’ve seen plenty of the male flowers like those shown here. Male flowers have 7 to 9 stamens with dark reddish anthers. Each male flower is about 1/8 of an inch across and dangles at the end of a long flower stalk (Pedicel.)

Male (staminate) box elder flowers (Acer negundo) are just showing in the recently opened buds. Once they begin to show like this things happen fast, so I’ll have to watch them.

Trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens) buds are showing color, so it won’t be too long before I can smell their wonderful fragrance again. It was my grandmother’s favorite wildflower because of that scent. Several Native American tribes considered the plant so valuable it was said to have divine origins, and I think she must have thought so too.

Trout lilies are up but so far leaves are all I’ve seen. The leaves always appear before the small yellow, lily like blooms. It won’t be long.

I was lying on my stomach at the edge of the woods trying to get this photo, just a few yards from one of the busiest highways in Keene, when I heard “Sir, is everything all right?” I looked up and found a young Keene Police officer looking down at me. I assured him everything was fine, thanked him for his concern, showed him the first spring beauty blossoms he had ever seen, and off he went. I thought afterwards that he had closed his car door, walked down an embankment full of crunchy oak leaves and stood right there beside me, and I hadn’t heard a thing. This, I thought, is a good example of becoming lost in a flower. I could imagine by his look of genuine concern what must have been going through that young officer’s mind. It can’t be every day that a policeman sees someone lying motionless in the weeds beside the road. At least, I hope not.

If you are lost inside the beauties of nature, do not try to be found. ~Mehmet Murat ildan

Thanks for coming by.