A few of us went for a walk today with Tom Ottley, the county bryophyte recorder, and had a brilliant session that covered key field characters of many heath species, a good overview of the local Sphagnums, and some unexpected rarities as well. The group included some near-beginners as well as those of us who have been learning about mosses and liverworts for a few years or more, so it was nice to have a good range of expertise present.

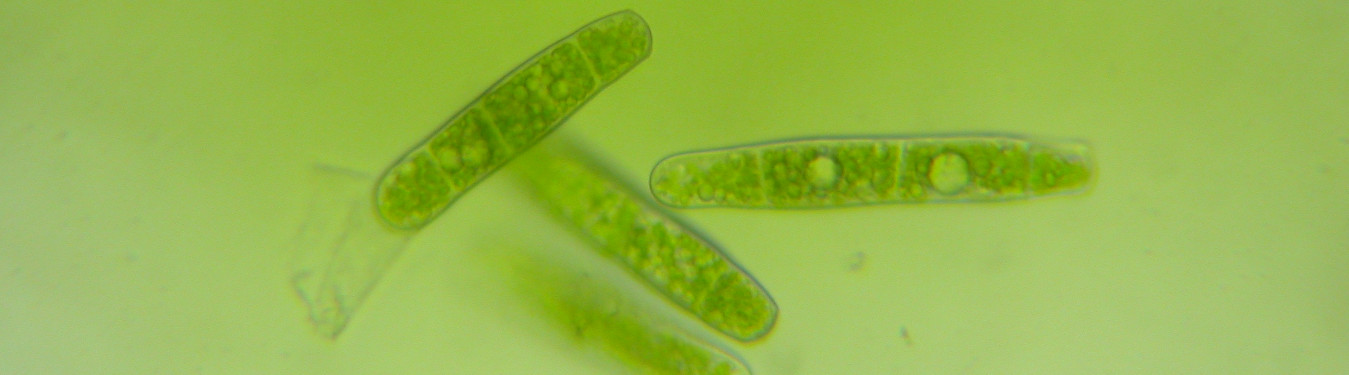

We started at the Ashdown Forest visitors centre and quickly identified some common heath plants: Hypnum jutlandicum, Dicranella heteromalla, Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus, Dicranum scoparium, Pleurozium schreberi, and also found a delightful pale green patch of Plagiothecium curvifolium growing on a stump on the edge of the wood, with its asymmetric leaves, and with large numbers of rod-like gemmae in the leaf axils (see main picture above).

Before we got too far down the hill we had the chance to compare several species in the family Polytrichaceae. First off was the common Polytrichastrum formosum on a tree stump, as well as on many of the forest banks. Its leaf margins are toothed, and the back of the leaf has a distinctive ridge just where it joins the stem.

Within a wetter part of the wood was Polytrichum commune. Its stems can be much longer than formosum and is more of a bog specialist. The back of its leaf at the leaf insertion is smoother than that of formosum and the leaves are usually narrower too.

Later on we were able to find Polytrichum juniperinum on open heath which is untoothed along its leaf margins, and has a reddish hair point to its leaves.

Once we reached an area of bog within the woodland edge we hit our first patch of Sphagnum, which contained five species. Sphagnum palustre is a common moss of woody habitats and is easy to recognise. It is quite pale and one of the relatively large Sphagnum species. Importantly, it has broad hooded branch leaves, the branches tend to be long and taper to a slender point, and if you break the stem you can see that it has an easily observable cortex in cross section. Another useful character is that, especially in winter, the centre of the capitulum is quite dark brownish.

The second, much greener species was smaller and much more slender than S. palustre. It was Sphagnum fallax. The branch leaves overlap each other in quite neat rows. They are also much narrower than palustre and not hooded. The stem leaves are pointed, and you can also see a pair of two short short hanging branches in the gaps between bunches of spreading branches when looking at the side of the capitulum.

In the same boggy area amid the birch was Sphagnum denticulatum. Like S. fallax it is often bright green in these shaded habitats, though can have more yellow and orangey tints in open spaces (or even darker brown when growing in really wet conditions), and is noticeably chunkier. From above, the branches below the capitulum tend to be curved and are often compared (somewhat tenuously) to cow’s horns. More usefully, the branches have a smooth outline as the leaves hardly project. The stem leaves are also longer and more rounded than those of S. fallax.

The fourth one was Sphagnum flexuosum, which used to be a subspecies of S. recurvum (along with Sphagnum fallax and the much rarer S. angustifolium, which we didn’t see today, though is also in the forest) before it was re-classified. Consequently, it has many features in common with its relatives being a slender species typical of boggy ground in woodland, but its stem leaves are blunt with a vaguely fringed tip. When looking at the plant as a whole the bunches (called fascicles) of two spreading branches and one or two pendant branches are noticeably well spaced out up the stem.

Then we found Sphagnum capillifolium ssp. rubellum, which is another smaller, delicate species, but with distinctive red tones. In woodland the redness may only be at the centre of the capitulum or completely missing, though in more open boggy spaces the whole plant is strikingly red. Unlike its relative (ssp. capillifolium) it has distinctively slender spreading branches projecting from the sides of the capitulum.

Heading down the hill we found some of the wetter open habitats in which other Sphagnum species occur. The chunky Sphagnum papillosum is distinctively ochre-coloured at this time of year, and the centre of the capitulum almost looks like it has a few grubs on it as the branches there are very short and blunt. It is in the same Sphagnum group as palustre, and has the similar hooded leaves and a wide cortex to the stem.

Also in the same group is the equally chunky, but much rarer, Sphagnum magellanicum. It too has very broad, hooded leaves but is another of the gorgeously red species, though is so different from S. capillifolium that the two can’t be mistaken. It is only known in Ashdown Forest in a handful of locations.

In contrast with the previous two, Sphagnum tenellum is much more delicate and fragile. It was in the wetter places, as well as among some of the spaces between the heather. It has yellow and golden coloration, and has two distinctive features: (i) the two terminal leaves of the spreading branches tend to be open like a bird’s beak; and (ii) its stem leaves are relatively massive and stick out from the stem, most species of Sphagnum having leaves which either point upwards or hang down against the stem.

Moving away from the very wet places, Sphagnum compactum is more of a species of damp heath, often growing with S. tenellum. As its name suggests, it is very tightly compact in its habit, and the leaves are so inrolled they look tubular with the ends of its leaves having almost parallel sides. It is surprisingly fragile, but if you can manage to peel away the branches it reveals a black stem (unlike the much rarer Sphagnum molle, which also lurks in the forest) and tiny, almost transparent, stem leaves.

Finally, our tenth Sphagnum of the day was Sphagnum cuspidatum, often likened to a drowned kitten in the way it looks in bog pools, the effect being produced by long narrow leaves at the ends of the branches that tend to stick together and hence appear matted.

That wasn’t a bad haul for the day, though other Ashdown Forest species which we didn’t see today include Sphagnum subnitens, Sphagnum fimbriatum and Sphagnum squarrosum, as well as the others I’ve also mentioned in passing.

Another group which we could compare over the course of the day was the genus Campylopus. The first one we saw was the common alien species Campylopus introflexus on a tree stump. It was first recorded in the UK in 1941 and has spread extensively since then. It has very distinctive white hyaline points on the leaf tips, which are often bent back (only when dry) and make the plant look like a star from above.

By contrast Campylopus pyriformis doesn’t have the white tips and was found on the path edge near the heather. It can be differentiated from Campylopus flexuosus (which also occurs in the forest) in not having orange/brown leaf bases. The final species from this genus was among the heather on the edge of the bog, and this was the much rarer Campylopus brevipilus. It was noticeably yellow with dense leaves up the stem and very small hair points.

The rest of our time was spent looking at a nice variety of liverworts, most of which were bog specialists, and the first of which was the small elongate Cladopodiella fluitans. Each leaf is well spaced from the next and has a notch between its rounded lobes.

A new record for the site was Cladopodiella francisci, which was on the heath away from the bog. Like C. fluitans it has a notch between the rounded leaf lobes, but is much smaller and the leaves are more closely packed together and tend to be pressed against the stem. Furthermore, Tom noted it has “triangular gemmae which are almost always lurking at the tip of the shoot”.

Back in the bog I was getting wetter as a result of kneeling down to take pictures of the small liverworts that grow through and alongside the Sphagnum. Kurzia pauciflora is another delicate species which, as the field guide says “resembles slightly frayed green thread” since its leaves are divided into three or four very fine lobes. The close relative Kurzia sylvatica also turned up today, higher up on the heath. Though the habitats for them tend to be different they also have microscopic differences too. Tom noted that it is important by measuring the width of the cells around the middle of the leaf lobes: “K. pauciflora is usually 17 microns or more whereas K. sylvatica is just under 15. There is a much more reliable way if you can find male inflorescences and measure their width. One other difference is that the apical cell of the lobes is acute(ish) in K. sylvatica and more rounded in K. pauciflora but that can be hard to judge.”

Another typical associate of the bog Sphagna is Odontoschisma sphagni, which has rounded un-notched leaves, and began to appear moderately commonly in one part of the bog once we knew what we were looking for.

It too has a relative which we found which was new for the site: Odontoschisma denudatum. It has much more attenuated upright shoots, typically with gemmae balls at their tip, making them look quite matchstick-like. This is a species which some of us had seen at the sandrocks of Friezland wood or Eridge rocks, though heathland is its more ‘normal’ habitat.

Even on the way back to the car park we kept finding interesting species. Lophocolea bispinosa is another alien species, first recorded in the Isles of Scilly in 1962, and has been spreading east ever since. Tom found it in the Forest a few years ago, and its bright green colonies are certainly extending rapidly and could certainly endanger some of the native liverwort species of this habitat. In some places you could see scuff marks where someone’s boot had dislodged a patch and then a few feet further down the track there would be a new colony growing. The plants are vigorous but fragile and that no doubt aids their dispersal.

One such plant it could endanger is Jungermannia gracillima, which was growing nearby, though not nearly as vigorously. Other species on sandy banks in that open part of the heath included Tritomaria exsectiformis and Lophozia ventricosa, the first of which appears to be a new record for the Forest and is a very rare liverwort in Sussex.

So, we had an extremely interesting and intense study of heaths and bogs over the course of our four-hour walk. Even though it is a spot I have walked often there was still a huge number of species I’d never noticed before. What an amazing place.

Huge thanks to Tom for leading the walk and for making some amendments and additions to this text.

[See also the post Ashdown Forest woodland bryophytes, which includes some of the species described here, as well as several others.]