Thistles are much-maligned and misunderstood. ‘Much-maligned’ because some are prickly garden weeds hated by most gardeners and farmers, and ‘misunderstood’ because of the loose meaning of the word ‘thistle’. However, we have often deployed stylised images of ‘thistles’ to symbolise pain and suffering, or protection and pride (as for example the floral emblems of Scotland and the Encyclopedia Britannica).

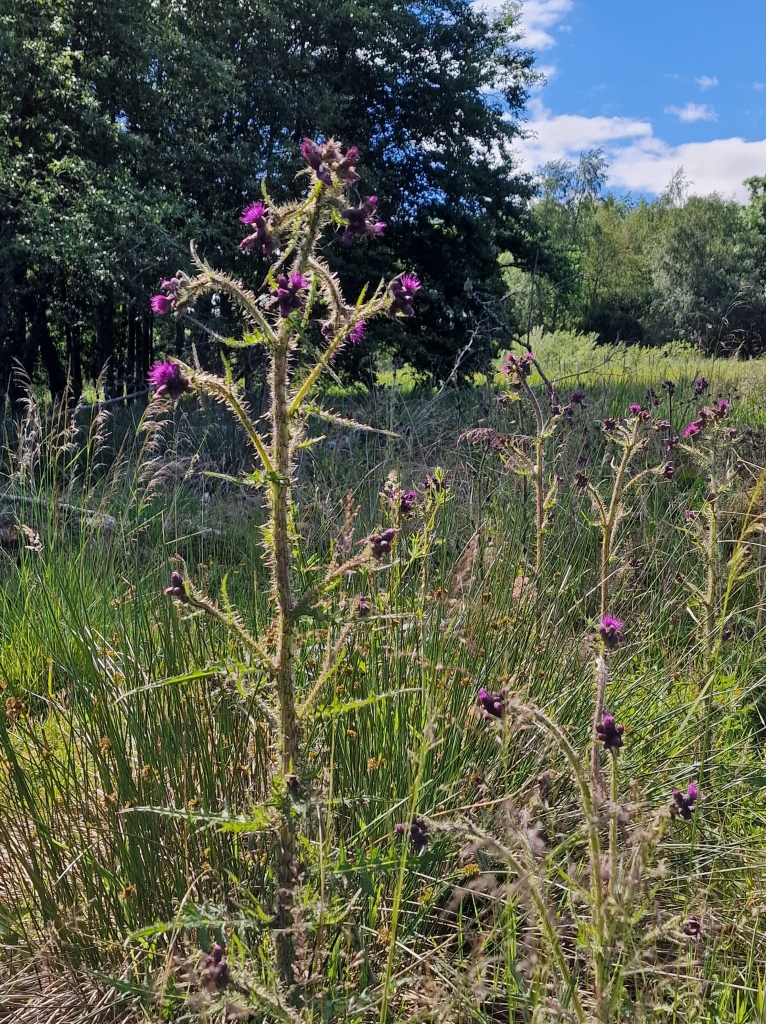

Cirsium palustre on marshland, Alyth, Perthshire. Photo: John Grace.

What about definitions? In the broadest sense, a thistle can simply be a hardy flowering plant with prickly leaves. But for botanists, thistles in the strict sense are members of just one branch of the Daisy Family (Asteraceae). They may be Cirsium (nine species of Cirsium in Britain) or Carduus (five species). But John Gerard in his 1597 Herbal clearly struggled with the definition: his ‘thistles’ include Acanthus (Bear’s Breeches) which is not even a daisy-flower. It is hard to decide which of his various thistles might have been what we know today as C. palustre.

C. palustre in bud, with buds ‘looking like young hedgehogs’. Photo: Chris Jeffree.

Among the Cirsiums, I do have my favourites. One of them is the Marsh Thistle. I first learned to recognise this one in my late teens when I visited Upper Teesdale in County Durham. My rambles in the uplands included peaty landscapes where the mighty River Tees is not-yet-mighty. This juvenile part of the river cuts through deep peat and is bordered by marshy ground with Agrostis-Fescue grassland. Two thistle species fascinated me: the Melancholy Thistle (Cirsium heterophyllum) and the Marsh Thistle (C. palustre).

Dense population of C. palustre in full flower. Photo: Chris Jeffree.

C. palustre thrives in wet places and Upper Teesdale is indeed a wet place (annual rainfall at Moor House is 1239 mm). But it doesn’t need high rainfall, just wet soil. Its habitats are stated by Strohl et al (2020) as: mires, fens, marshes, damp grassland, rush-pastures, wet woodland, montane springs and flushes, and tall-herb vegetation on mountain ledges. In fact, it is a common plant throughout the British Isles because even the driest parts of Britain have some wet areas.

The plant is a native of Europe (including Britain) and Western Siberia, first described in Britain by botanist Thomas Johnson (1600 – 1644) in 1634. When well-grown it is described as a biennnial, growing as a rosette in its first year and producing its flowering stem in year 2. However, some authors regard it as a ‘monocarpic perennial’ as it can take two years or much more before it produces flowers (after that it dies, so it isn’t a true perennial). The flowering stem is tall (0.5-2 metres) straight and only sparsely branched. The whole plant has very prickly leaf margins, the prickles being the main means of defence against grazing animals. The stem is described as ‘winged’, meaning that photosynthetic tissues extend outward from the stem to some extent.

Flower-heads when flowering has almost finished. The mass of ‘parachutes’ (each achene has a ‘pappus of hairs’) is called thistledown and has been used traditionally to stuff pillows. Photo: Chris Jeffree.

The plant is generally tinged red/purple as shown in the images. There are however albino forms with white flowers, frequent in some populations. Mongford (1974) described the typical purple flowered morph, a white flowered morph, and two intermediate morphs. He reported the white form to be more common at higher elevations, an unexpected result as the pigment anthocyanin usually develops more strongly in stressed situations (see Richard Milne’s discussion here).

David Valentine, a former President of the BSBI, argued that such morphs, although they differ from each other by only one or two genes, ought to be formally recognised in the taxonomic system at the level of forma (Valentine 1975). In practice, this is seldom done.

Detail of the stem, showing red pigmentation, and spiny ‘wings’ on the stem. Photo: Chris Jeffree.

In the British context, recent research on thistles is dominated by their importance as sources of pollen and nectar for pollinating insects. I was astonished to read that only four species of plant, Trifolium repens, Calluna vulgaris, Cirsium palustre and Erica cinerea, together produce over 50% of nectar nationally (Baude et al 2016). I would like to see how the rather few actual measurements were extrapolated to the national scale (have some rather wild assumptions been made?). From my own casual observations I would expect Cirsium arvense (the Creeping Thistle) would exceed C. palustre as a nectar resource simply because it is more frequent and forms dense populations which bees love. Notwithstanding my objection, the fact remains that thistles are of national importance in the fight to conserve our threatened populations of wild bees (Hicks et al. 2016). Thistles are also of importance as a food source for butterflies, moths, and some small birds.

Apart from the several publications on pollination and pollinators, and a good summary in Grime et al (1987), rather little work has been done on the ecology of Cirsium palustre in Britain. But in North America there is much more interest, as C. palustre (called the European Marsh Thistle) is an invasive alien (see here). It was introduced into New Hampshire and Newfoundland in the early years of the 20th Century, and has spread. The accounts suggest it is not especially serious as a pest, but a ‘concern’ with the potential to become another one of those ‘noxious European weeds’. The authors focus on control measures using various pests brought from Europe including the European seedhead fly, Terellia ruficauda and the seed-eating weevil, Rhinocyllus conicus. The weevil lays about 100 eggs on the flower-heads of thistles and covers them with masticated plant material. Later, the larvae emerge and feed voraciously on the flowers. The trouble is, native North American thistles are attacked as well, and so the use of imported European control agents has become controversial (Rose et al. 2005).

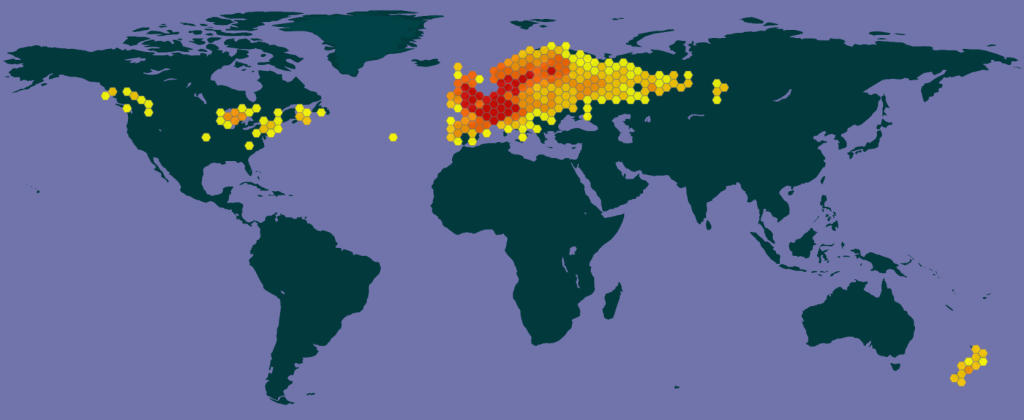

The Marsh Thistle has spread to many parts of the world, as shown in the maps that are freely available from GBIF. Its appearance in New Zealand was not until 1930 and, strangely, it hasn’t yet been recorded in Australia.

Global distribution of C. palustre according to GBIF.

Thistles have symbolic meaning, and If you are Scottish, you might like to look at Maria Chamberlain’s 2021 blog where she attempts to identify which species of thistle is the National Flower. For me, it doesn’t really matter because no-one knows which thistle defeated the gang of sea-faring Danes when they trod on it with their sandalled feet (silly boys for wearing inappropriate footwear in Scotland).

A fine poem about thistles was written by Ted Hughes (poet laureate from 1984 to 1998). Hughes was raised in the harsh surroundings of the Calder Valley in West Yorkshire, and that harshness often emerges in his work. His poems are not ‘easy’ but I think the ‘decayed Viking’ must be the Nordic invader who trod on a thistle. In the final verse of this poem the thistle becomes a metaphor for the ordinary working man.

References

Hicks DM et al. (2016) Food for Pollinators: Quantifying the Nectar and Pollen Resources of Urban Flower Meadows. PLoS One. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0158117

Baude M et al. (2016) Historical nectar assessment reveals the fall and rise of floral resources in Britain. Nature 530, 85–88. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16532

Grime JP et al. (1988) Comparative Plant Ecology: A Functional Approach to Common British Species. Chapman & Hall..

Mogford D J (1974). Flower colour polymorphism in Cirsium palustre. Heredity 33, 257–263https://www.nature.com/articles/hdy197490

Rose KE et al. (2005) Demographic and evolutionary impacts of native and invasive insect herbivores: a case study with Platte thistle, Cirsium canescens. Ecology 86: 453-465.https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/56704.pdf

Strohl PA et al. (2020) Cirsium palustre (L.) Scop. in BSBI Online Plant Atlas

Valentine DH (1975) The taxonomic treatment of polymorphic information. Watsonia 10, 385-390.https://archive.bsbi.org.uk/Wats10p385.pdf

©John Grace