My best memories of Bird Cherry are from springtime visits to the Scottish Highlands in our beaten-up Voltswagen van. I would stop at any signs of spring blossom to try to identify the flowers using my every-ready and much-thumbed copy of Fitter et al. (1974). I have always found spring flowers of Prunus confusing as there are several species and many horticultural introductions, but once you realise that Bird Cherry has its flowers arranged in racemes1 the identification becomes easier.

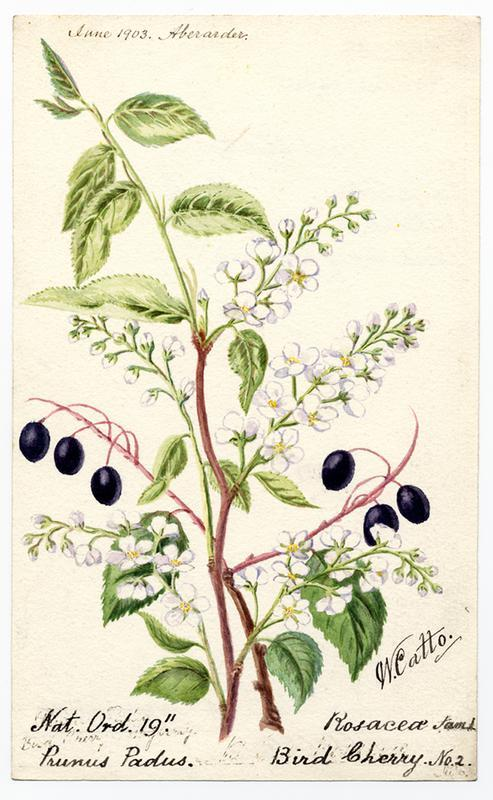

Original book source said by Wikipedia to be by Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé from Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz 1885, Gera, Germany. However, the signature, heading and handwriting suggests this has been a mistake and that the real artist was an Aberdeen man William Catto. Aberdeen Art Gallery, via Wikimedia Commons

This is a common tree in Scotland, and I had thought of it as a Scottish tree. However, the recent botanical atlas (Stroh et al. 2023) shows that it is now widespread over much of Britain, having been planted in parts of England and Wales where it had rarely been recorded. In Ireland, it is still predominantly northern.

It is truly native. In the north of Britain, fruit stones have been found in deposits dating from the Pleistocene epoch (Leather 1996). There are also historical records. Gerard recorded it in his 1597 Herbal2. He found that in Lancashire it was “in almost every hedge”. These hedges are, I fear, long-gone (and he may have exaggerated). Arthur Tansley, in his classic 1965 book British Islands and their Vegetation says it is “quite frequent in the woods at higher altitudes in some parts of the north and west, but does not occur wild in the south..”

Prunus padus growing wild along the River Kelvin, Glasgow. Photo: Chris Jeffree.

The tree reaches 3-15 metres in height and tends to form thickets or scrub, owing to its tendency to produce ‘suckers’ in the same way as its relative, Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa). It tolerates shade and can form the understory of oak woodlands, as it does at Loch Lomond in Scotland. Often, it is associated with upland woodlands of ash (Fraxinus excelsior). It prefers fairly nitrogen-rich and calcium-rich soils, avoiding acidic sandy soils.

Prunus padus showing general arrangement of a branch, festooned with racemes of white flowers. Photo: Chris Jeffree.

It has the typical flower of the rose family, Rosaceae: fragrant, cup-shaped with five petals and sepals, hermaphrodite, many stamens and pollinated mostly by flies and bees. The ripe fruit is a pea-sized black cherry, extremely bitter for humans although made into tarts in some countries. However, birds don’t seem to mind the bitterness, especially thrushes, robins and warblers. Some beetles like the cherries (Leather 1996) and I have read that mammals such as badgers and mice will eat them; however, there are also records of livestock being poisoned by the cyanogenic glycosides found especially in the bark and seeds.

Prunus padus raceme (left) and detail of individual flower (right). Photo: Chris Jeffree.

The glycosides prunasin, prulaurasin and amygdalin are part of the plant’s defence against herbivores and pathogens. These compounds are stored within the vacuoles of plant cells but when tissues are crushed (as in chewing) they come into contact with enzymes which break them down and release the toxic gas cyanide (it smells of almonds). Despite this formidable defence, twenty-eight species of insect have been recorded as feeding on P. padus in the British Isles (Leather 1996).

Prunus padus leaves. Underside of leaf with hairs mostly on the veins. Photos: Chris Jeffree.

Another defence system involves attracting ants by producing nectar from special glands on the leaf stalks. Nearly all Prunus species have ‘extrafloral nectaries’ excreting sweet-smelling odours that ants head for. The ants will also attack any insects that may be around, including hungry caterpillars and aphids. The most remarkable aspect of this phenomenon is described in an article by Pulice and Packer (2008). Working with Prunus avium in a greenhouse they simulated caterpillar attack by damaging leaves using a hole-punch or scissors. The plants responded by producing more of these extrafloral nectaries. Sending for an ant-army, and paying the soldiers well, is a good way to defend plant-tissues against herbivores.

Examples of Prunus nectaries. Left: P. padus, right: P. cerasifera. Photos: Chris Jeffree.

Despite being bitter, and having toxic stones, Bird Cherry has long been used to flavour spirits. Today, distillers all over Scotland are making ‘botanical’ gin. The characteristic flavour of gin comes from Juniper berries but other ingredients may be added to make a craft gin. The Speyside Distillery, in its Byron’s Gin range, have a gin called Bird Cherry. This is what their publicity says:

“To select the botanicals for this boutique gin, head distiller and master craftsman Sandy Jamieson sought the help of Andy Amphlett, County Recorder for the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland and Byron’s Gin is now the official gin of the Botanical Society.

The resulting collaboration infused their professional skills, expertise in their respective fields and most importantly their deep passion and produced two expressions of Byron’s Gin – Bird Cherry and Melancholy Thistle – creating a unique and new gin experience for the more sophisticated palate”.

Do I have ‘the more sophisticated palate’? Not really. The last time I purchased gin I was asked “which one” and I said “one that tastes of gin, please”. Call me old-fashioned but I like mine to taste of unadulterated juniper.

In former times Bird Cherry was valued by humans much more that it is today. Nestby (2020) describes its use for ‘minor forest products’ in Europe and Asia:

“..people still collect berries to make syrup, jam and liquor. Moreover, the wood is attractive for wood carving and making cabinets, and has value as firewood. More importantly, it is concluded that bird cherry fruits, leaves and bark may be valuable sources of powerful natural antioxidants for use in food, medicine, cosmetics and other fields currently processing antioxidants”.

My search for Prunus padus on the Web of Science confirms the last sentence: many of the articles published in the last two decades relate to the chemistry and possible pharmaceutical value of extracts from flowers, fruit and bark. A good review of the huge body of literature is here. In former times the bark of bird cherry was used as a pesticide. Its medicinal uses were for a cough medicine and to treat conjunctivitis, kidney stones, bronchitis and anaemia.

A possible future use, taking full advantage of its ‘suckering’ tendency, is to bind soil and therefore to stabilize alpine slopes that are prone to erosion.

Distribution in Britain and Ireland. Left: up to the year 2000; right: since 2000. From BSBI/maps.

The name of the species causes confusion. Prunus avium (Wild Cherry) sounds as if it should be the one called Bird Cherry. We can blame Linneaus, who named and described most of the European cherries in his Species Plantarum of 1753. I have not discovered why the specific name of Bird Cherry is padus, the Latin name for the River Po in Italy. Did Linneaus have a nice holiday in Lombardy? Making matters worse, Russian taxonomists call Bird Cherry Padus racemosa.

The English name Bird Cherry is definitely ‘old’ (used by Gerard and very descriptive as birds consume the berries). It is called Hagberry in the northern parts of Britain as it was supposed to be a witch’s tree (‘witch’ and ‘hag’ are almost synonyms). If you are interested in languages to can find a list of its vernacular names for Bird Cherry in other regions of the world here. I was intrigued to see the Swedish vernacular name is Hägg but that isn’t the same as ‘hag’. Possibly the association with witches comes from a misunderstanding of what Hägg means in Swedish – there, it’s merely a common surname.

Prunus padus, native to Europe and Asia; introduced to Alaska, Argentina South, Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, Montana, New Brunswick, New Jersey, New York, Ontario, Pennsylvania, Utah, Uzbekistan, Washington.

The freshness and beauty of spring flowers often inspire poetry and song. Cherries of various kinds often appear but I found only one poem about Bird Cherry. Here is the poem by Roshni Gallagher, a young poet from Leeds who now lives in Edinburgh.

Notes

1raceme is a common type of inflorescence where the flowers are on short stalks coming from a spike. Bird Cherry is a good example.

2Gerard’s description of the locations of the species was especially long, and unusually for him, he mentions sites in the north of England. The species was then called Cerasus avium, Bird Cherry or Black Cherry. He says: “..that bringeth forth very much fruit upon one branch (which better may be understood, by sight of the figure, than by words) springeth up like an hedge tree of small stature, it groweth in the wild woods of Kent, and are there used for stocks to graft other Cherries upon, of better taste, and more profit, as especially those called the Flanders Cherries: this wild tree grows very plentifully in the North of England, especially at a place called Heggdale, neer unto Rosgill in Westmorland, and in divers other places about Crosby Ravenswaithe, and there called Hegberry tree: it groweth likewise in Martome Park, four miles from Blackburn, and in Harward near thereunto; in Lancashire almost in every hedge: the leaves and branches differ not from those of the wild Cherry tree: the flowers grow alongst the small branches, consisting of five small white leaves, with some greenish and yellow thrums in the middle: after which come the fruit, green at the first, black when they be ripe, and of the bigness of sloes; of an harsh and unpleasant taste”.

References

Fitter A et al. (1974) Wild Flowers of Britain and Northern Europe. Collins.

Leather SR (1996) Prunus padus L. Journal of Ecology 84, 125.

Nestby RDJ (2020) The Status of Prunus padus L. (Bird Cherry) in Forest Communities throughout Europe and Asia. Forests 11, 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11050497

Pulice CE and Packer AA (2008) Simulated herbivory induces extrafloral nectary production in Prunus avium. Functional Ecology 2008, 22, 801-807 doi: 10.1111/j.l365-2435.2008.01440.x

©John Grace