Cerastium plants do not attract the attention of humans unless they are growing in the garden as a weed. They are rather small, their flowers are tiny and commonly shut, and they often grow entangled with other species. There are perhaps 200 species of Cerastium worldwide, and in Britain we have eleven species. Two are very common, I see them every day and they bring a smile to my face. Two others are occasionally seen but botanists need sharp eyes and a hand lens to record them. They are easily missed and and so they may be more common than they seem. The remaining seven are relatively rare – confined to specific habitats.

Representatives of the Family Caryophyllaceae. The Common Mouse-ear Cerastium fontanum is the one on the top right corner. Cerastium is derived from the Greek word for ‘horned’, referring to the shape of its fruit capsule (see item 6 in the picture). The illustration shows two Sandworts and one Stichwort, but their capsules are quite different. Note that three species have changed their names since this picture was painted in 1901 by Carl Axel Magnus Lindman – Bilder ur Nordens Flora (1901-1905). Cerastium caespitosum is now Cerastium fontanum, Alsine biflora is now Minuartia biflora (Mountain Sandwort), Alsine stricta is now Sabulina stricta (Teesdale Sandwort). Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3419869.

Mouse-ears (Cerastium) were formerly called Mouse-ear Chickweeds, as they resemble their close relatives the Chickweeds (genus Stellaria). Cerastium is like Stellaria except for its distinctly hairy tendencies and differences in its floral biology. It’s best to follow the example set by most modern authors and simply call all Cerastium species ‘the Mouse-ears’.

Cerastium belongs to the Caryophyllaceae, the Family of Carnations and Pinks, characterised by having opposite pairs of usually untoothed and unstalked leaves with petals that are often notched. And yes, the leaves look like the ears of the mouse.

Common Mouse-ear, Cerastium fontanum The most common of all is Cerastium fontanum, appropriately called Common Mouse-ear. It was first described by Thomas Johnson in 1634, a man once called “the best herbalist of his age in England,” and “no less eminent in the garrison for his valour and conduct as a soldier.” He revised Gerard’s Herbal, correcting mistakes and adding about 600 new species.

Common Mouse-ear. Note the sprawling habit and the dark green colour. Image: Chris Jeffree.

Common Mouse-ear is practically ubiquitous in Britain and Ireland but it does have a most uncommon subspecies Cerastium fontanum subsp. scoticus first described in 1967 which lives only at the head of Glen Doll in Angus. Let’s put that one aside for now – if I manage to get to Glen Doll in the coming months I’ll write about it. Common Mouse-ear is found in meadows, pastures, waysides, demolition sites, wasteland, mires, cultivated land, shingles and sometimes in woodlands. It thrives in plant-crowded habitats: Grime at al (1988) usually found it with about 20 other companion species in its own square metre.

It is a low-growing perennial that stays green in winter and tends to sprawl and creep. Vegetative shoots are mostly horizontal but it sends up flowering shoots and can produce up to 6,500 small seeds in a year according to Salisbury (1964). The same author says the seeds persist in the soil for 40 years, and they may travel around the country as contaminants of grass seed mixtures. It grows well in my allotment, behaving like an annual: it germinates in the autumn (we don’t practice ‘autumn digging’ but some plot-holders still do), and now (April) it is starting flower. I will need to remove it to make way for my beans.

Flowers of Common Mouse-ear, each on a short stalk and with rather deeply notched petals. An aphid is trying to find a feeding site on the hairy stem. Image: Chris Jeffree.

It is usually quite hairy all over, and the hairs look whitish. Macro-photography shows them to be a filaments made of several long thin cells. We will return to hairs later.

Common Mouse-ear. Enlarged image of sepals to show the hairs are simple, apparently made of a file of up to five cells with an orange-coloured septum separating the individual cells. Note also the edges of the sepals are semi-transparent and look silvery. Image: Chris Jeffree.

Sticky Mouse-ear, Cerastium glomeratum. Common Mouse-ear can be confused with Sticky Mouse-ear, Cerastium glomeratum. This one is also a native species; early botanists called it The Broader-leaved Mouse-ear-Chickweed (Pearman 2017).

Sticky Mouse-ear at the edge of a pavement, next to a wall. Note: tight cluster of flowers, upright habit and colour is yellowish-green. Photo: John Grace.

The ‘Sticky’ feel is the result of its covering with glandular hairs, quite distinct from the whitish hairs (which it also has). Each glandular hair terminates in a globular structure and secretes sticky mucilaginous substances. I have not been able to find anything published on the composition of the mucilage, but the general assumption is that stickiness is part of the plant’s defences against herbivores. The Sticky Mouse-ear is seldom visited by insects and is self-pollinated; according to Salisbury (1961) it is sometimes cleistogamous (i.e. self-pollination occurs when the flower is closed). Perhaps that’s because insects cannot climb the sticky stem. I usually see particles of soil stuck there, and I like to think that some of the plant’s nutrition is derived from wind-blown particles. It is an untested hypothesis.

There are recent suggestions that plant hairs are for sound detection. They vibrate when insects are chewing the plant’s tissues, giving the plant the opportunity to prepare chemical defences (Demey et al. 2023).

Sticky Mouse-ear to show flowers (5 notched petals, 10 stamens, clusters of almost stalkless flowers) and zooming in to show the glandular hairs that make the plant sticky. Photos: Chris Jeffree.

In contrast to the Common Mouse-ear, the plant is often pale green and its flowers are generally in a tight cluster. Earlier authors called it Clustered Mouse-ear Chickweed (Salisbury 1961).

Cerastiums are rarely used by herbalists, but perhaps they found a few uses in former times. For C. glomeratum, we are told by wikipedia: “the leaves and shoots were used as a wild food in ancient China. In Nepal, the juice was applied to the forehead to relieve headaches. It was dropped into the nostrils to treat nosebleeds”.

I see this plant in many urban settings. In the street where I live it thrives in the angle between pavements and walls, and is one of several species that seem to be resistance to the herbicide sprays of Council workfolk. Stroh et al. (2023) say that it has become more common in the last two decades, particularly in Ireland and Northern Scotland.

Little Mouse-ear, Cerastium semidecandrum. In the last two weeks we have been on our hands and knees searching for two other Cerastium species, the Little Mouse-ear C. semidecandrum and the Sea Mouse-ear C. diffusum. We think C. semidecandrum has been under-recorded, and so I was keen to see what Stroh et al. (2023) have to say on the matter in the recent 2-volume 1524-page book (it’s a magnum opus but it weighs 8 kg). They write:

“C. semidecandrum was under-recorded before the 1960s but its coverage has improved since then and new sites continue to be found across its range with the map now representing a more accurate picture of its true distribution. There have been some localized declines this century which may be due to agricultural intensification, fertilizer addition, nitrogen deposition, changes in grazing management and land development. It is restricted to coastal regions in Ireland”

Little Mouse-ear growing at Musselburgh, showing its short stature and crowded shoots, and close up to show that flowers have only 5 stamens. Photo: Chris Jeffree.

Little Mouse-ear has both glandular and non-glandular hairs. The sure way to identify it is simply to count the stamens. The clue is in the name. Those who did Latin at school will realise that semidecandrum means that it has half-of-ten stamens, i.e. 5 stamens. Also the petals are only slightly notched. Of course, there are some other characters too, well-described in Clapham et al (1987), but the stamen count immediately separates it from the Common and the Sticky which have ten. It is found on calcareous and sandy soils, including dunes.

Sea Mouse-ear, showing 4 slightly-notched petals growing by the side of a rough road less than 1 km from the coast in Ayrshire, early April 2023. Image: John Grace.

Sea Mouse-ear, Cerastium diffusum. Finally, the Sea Mouse-ear C. diffusum can be distinguished by having only 4 petals instead of the usual 5; and it has only 4 stamens. It is an annual with short glandular hairs, rarely visited by insects and it is self-pollinated. It is to be found by the seashore on sand dunes, shingle, rocks, cliffs and walls. It is small and easily overlooked. I found it at Ballantrae in South Ayrshire by the rough road leading to the TV transmitting tower, within 1 km of the sea.

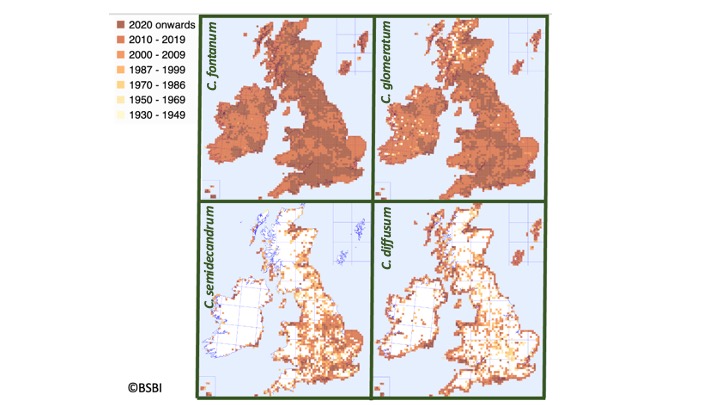

The distribution of the four species in this blog, downloaded from the BSBI/Maps site on 22/04/2023. Note that for both C. semdecandrum and C. diffusum many of the former sites are no longer occupied. Also note that C. semdecandrum is more common on the east, whereas C. diffusum has a more western distribution.

The global distribution patterns reflect the historical migration of Europeans to other parts of the world. Plant species tend to hitch a lift on boots and clothes of immigrants, and often the alien species are invasive in their new environments because natural enemies (herbivores and fungal diseases) are missing. It seems that the Sticky Mouse-ear has travelled the most.

Global distribution of the four Mouse-ears, all native the Britain and much of Europe. It is the Sticky Mouse-ear (C. glomeratum) which has travelled most. Note that the Sea Mouse-ear (C. diffusum) is by no means confined to coastal locations.

Another way to compare the species is to look at their ecological characteristics using the ratings provided by Heinz Ellenberg the German ecologist who liked to score species according to their requirements or tolerances to Light, Moisture, Reaction to acidity in the soil, Nitrogen requirement and Salt tolerance. His work was adapted for application to British conditions by Mark Hill and colleagues. The comparison shows how the Sticky Mouse-ear C. glomeratum has a preference for moister soils with a high nitrogen content.

This survey of Mouse-ears has covered only the top four species. As a group, they pose some interesting questions relating to pollination biology, the role of plant hairs, plant geography, the meaning of notched petals, the responses to nitrogen deposition from atmospheric pollution and evolutionary dead-ends brought about by cleistogamy. I’m going to pay more attention to them in future, and see whether I can find the rarer members.

References

Clapham AR et al. (1987) Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge University Press.

Demey ML et al. (2023) Sound perception in plants: from ecological significance to molecular understanding Trends in Plant Science. doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.

Pearman D (2017)The Discovery of the Native Flora of Britain and Ireland. BSBI.

Salisbury E (1964) Weeds and Aliens, Collins.

Stroh PA et al. (2023) Plant Atlas 2020 – mapping changes in the Distribution of British and Irish Flora. BSBI & Princeton University Press.

©John Grace with inputs from Chris Jeffree