Someone once said that Shepherd’s Purse is among ‘the world’s worst weeds’ (Holm et al., 1977). That’s a little unkind. Given the usual human-centric definition of a weed as ‘a plant growing where we don’t want it’ I can think of many that are much worse. Here are its credentials.

Capsella bursa-pastoris, Johann Georg Sturm, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s usually a small plant (< 40 cm), with the flowering stem growing from a rosette of leaves. It can withstand a wide range of conditions, including hard frost (temperatures down to -12 oC ). It is short-lived, and grows and flowers in both winter and summer. It produces seeds mostly by self-pollination (a few thousand seeds per plant, a modest reproductive effort for a weed). Its seeds can survive in the soil for 35 years and they are quite indifferent to passage through the guts of birds and earthworms. There is a tap root but not one that is deep and fibrous like many weeds – a child can pluck the root from the ground with ease. Many weeds require a hefty spade and strong arm to uproot.

General structure of the plant with flowers and fruits. Photo: Richard Milne.

It is quite variable in form. Because it is mostly self-pollinated, and many seeds from one plant are scattered within a metre of their source, local populations of strongly similar individuals are seen. In older books, some of these are even given names as if they were distinct species. Salisbury’s classic book Weeds and Aliens, published sixty years ago talks about ‘in some species…’ whereas today we say that Capsella bursa-pastoris is just one species, albeit a variable one.

Does it do much harm? Many of the ‘worst weeds’ are strong competitors with leaves that smother crops and reduce yields but Shepherd’s Purse is not one of those. It cannot survive in grasslands or cereal crops, and is most often seen in open conditions where land is uncultivated, neglected or abandoned. It is frequent in the urban flora, and it often found by roadsides, pavements and around car parks. Indeed, the first known description, by William Turner in 1548, said it ‘groweth by highways almost in every place’.

Shepherd’s Purse, rosette stage. Note the deeply pinnatified leaves. Photo: Chris Jeffree.

Salisbury (1961) describes the main dispersal mechanism:

“If ripe seeds be placed in water, a thin layer of mucilage can be seen under a microscope to swell up, and this, together with the flattened shape, ensures ready adhesion to the feet of birds, which also feed upon the seeds….(it is) also dispersed in mud on tools and implements, as well as on boots and motor tyres”.

Horses’ hooves and the wheels of carriages must have dispersed it rather efficiently in William Turner’s day.

In Britain you will almost certainly find it within a short walk from where you live, and it occurs in all the Vice-Counties. Globally, the centre of distribution is West Asia and Eastern Europe but it is naturalised across much of the temperate and subtropical world – apparently it is ‘an ardent follower of man’, thriving in urban areas and gardens, surviving dry conditions in the Nile Valley and reaching an elevational limit of 5900 metres in the Himalayas. It is said to be the most widely distributed of all weeds. So, rather than being the ‘world’s worst weed’ it may be dubbed ‘the world’s most successful weed’.

Flowers and fruits can be found in all months of the year, but most are seen in spring and summer. This image is from winter (December 2022): the plant can tolerate winter conditions. Photo: John Grace.

Descriptions of the ecology of this species are in Grime et al (1987) and Aksoy et al (1998). Shepherd’s Purse is a very ‘plastic’ species, living almost anywhere but avoiding water-logged soils, acid soils and thriving on disturbed fertile ground, mostly restricted to flat or gently sloping terrain.

It belongs to the Brassicaceae (the Family of cabbage and mustard) and is closely related to several other weeds of small stature including Erophila verna (Whitlow Grass) and Arabidopsis thalliana (Thale Cress), but it is hard to mistake Shepherd’s Purse for anything else. It has the characteristic fruits, triangular or heart-shaped, presumably like a shepherd’s purse from days of old (and the seeds are not unlike little coins). The flowers are white with the characteristic four petals as in all the Brassicaceae. Rarely, pinkish versions occur as it can hybridise with Capsella rubra, a pink ‘casual’ coming from southern Europe.

Detail of flowers. Photo: Chris Jeffree,

It tastes somewhat of cabbage and some people in North America grow it as a salad crop. It is a food plant in China and Korea, used especially in soups, and in Europe it is well-known to foragers. The younger leaves are eaten raw or cooked and we are told ‘The flower tips can be eaten as a snack while out walking’. I must remember that.

Fruits are shaped like a shepherd’s purse from medieval times (probably shepherds used a simple bag of leather with a draw-string). Photos: Chris Jeffree.

There is a biological peculiarity in this species, a feature that is by no means unique in the plant kingdom but worthy of mention. The chromosome number can be either 16 or 32 (diploid or tetraploid). According to Stace (2019), when the count is 16 the fruits are smaller and the leaves are more dissected. Plant evolution does often occur through polyploidy whereby the chromosome counts are doubled or quadrupled. In this case, Kasianov et al. (2017) suggest that ‘polyploidization’ in C. bursa-pastoris enhanced its plasticity of response to light and temperature, and allowed substantial expansion of its distribution range.

It has long been considered to be a medicinal plant. In my childhood I kept rabbits, and I was informed by villagers that a sure cure for the (frequent) diarrhoea of my furry friends was Shepherd’s Purse. It always worked wonders. I have also read that it is fed to young calves after they have been purchased at the market. These creatures often have diarrhoea because of the change in diet and perhaps also because they are terrified. It’s allegedly good for many human ailments. Culpeper’s Complete Herbal says it stops bleeding, ‘flux of the belly’, the ‘terms in women’ and when administered as drops to the ears, it heals ‘pains, noise and mutterings thereof’. The best description I can find of its use as a traditional herbal medicine is here. It was sometimes used to stop internal and external haemorrhaging during the Great War. It has been made into a cold tea to staunch nosebleeds.

Young shoot in a leaf axil. Note the small bristles that make the leaves feel rather rough, also note the leaf bases clasping the stem. Photo: Chris Jeffree.

It is clearly has potential in modern medicine, but it has been woefully under-researched. One example of a controlled clinical trial to see whether it can reduce bleeding is described by Ghalandari et al (2017). It was indeed effective.

If you live in Scotland or are planning a visit, please read this paragraph. Otherwise you are advised to skip it. My colleague Richard Milne has realised that CAPSELLA makes a mnemonic for remembering the coastal towns of Fife from North to South: Craill, Anstruther, Pittenweem, St. Monans, Elie, Lower Largo, All the rest.

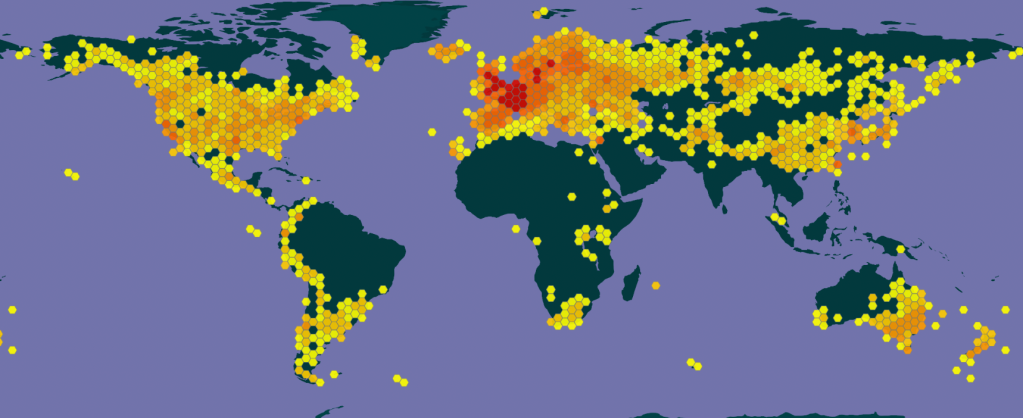

Shepherd’s Purse has a cosmopolitan distribution, having colonised all continents except for Antarctica. It thrives in all climatic regions except for desert and the humid tropics. Data from GBIF.

Shepherd’s Purse has had many names. Culpepper’s Complete Herbal has these: Whoreman’s Pharmacety, Shepherd’s Scrip (that’s a wallet), Shepherd’s Pounce (that’s a bird’s claw), Toywort, Pickpurse, Casewort.

References

Aksoy A et al (1998) Biological flora of the British Isles. Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medikus (Thlaspi bursapastoris L., Bursa bursa-pastoris (L.) Shull, Bursa pastoris (L.) Weber). Journal of Ecology 86, 171-186.

Ghalandari S et al (2017). Effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Capsella bursa pastoris on early postpartum hemorrhage: A clinical trial study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 23, 794‐799.

Grime J P et al (1988) Comparative Plant Ecology. A Functional Approach to Common British Plants and Communities. Springer.

Holm LG et al. (1977) The World’s Worst Weeds; distribution and biology. East-West Center, University Press of Hawaii.

Kasianov AS et al (2017) High-quality genome assembly of Capsella bursa-pastoris reveals asymmetry of regulatory elements at early stages of polyploid genome evolution. Plant Journal 91, 278-291.

Salisbury E (1961) Weeds and Aliens. Collins, London.

Stace C (2019) New Flora of the British Isles. 4th edition. C&M Floristics.

©John Grace