European Golden-Plover Pluvialis apricaria Scientific name definitions

Text last updated February 1, 2016

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Gjelaci pikalosh ngjyrë ari |

| Arabic | زقزاق ذهبي اوروبي |

| Armenian | Ոսկեփայլ քարադր |

| Asturian | Pilordu dorñu europñu |

| Azerbaijani | Qızılı qonurqanad |

| Basque | Urre-txirri europarra |

| Bulgarian | Златиста булка |

| Catalan | daurada grossa |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 歐金鴴 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 欧金鸻 |

| Croatian | troprsti zlatar |

| Czech | kulík zlatý |

| Danish | Hjejle |

| Dutch | Goudplevier |

| English | European Golden-Plover |

| English (UK) | European Golden Plover |

| English (United Arab Emirates) | European Golden Plover |

| English (United States) | European Golden-Plover |

| Faroese | Hagalógv |

| Finnish | kapustarinta |

| French | Pluvier doré |

| French (France) | Pluvier doré |

| Galician | Píllara dourada europea |

| German | Goldregenpfeifer |

| Greek | (Ευρωπαϊκό) Βροχοπούλι |

| Hebrew | חופזי זהוב |

| Hungarian | Aranylile |

| Icelandic | Heiðlóa |

| Italian | Piviere dorato |

| Japanese | ヨーロッパムナグロ |

| Latvian | Dzeltenais tārtiņš |

| Lithuanian | Dirvinis sėjikas |

| Norwegian | heilo |

| Persian | سلیم طلایی اروپایی |

| Polish | siewka złota |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Tarambola-dourada |

| Romanian | Ploier auriu |

| Russian | Золотистая ржанка |

| Serbian | Zlatni vivak |

| Slovak | kulík zlatý |

| Slovenian | Zlata prosenka |

| Spanish | Chorlito Dorado Europeo |

| Spanish (Spain) | Chorlito dorado europeo |

| Swedish | ljungpipare |

| Turkish | Altın Yağmurcun |

| Ukrainian | Сивка звичайна |

Pluvialis apricaria (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- PLUVIALIS

- pluvialis

- apricaria / apricarius

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

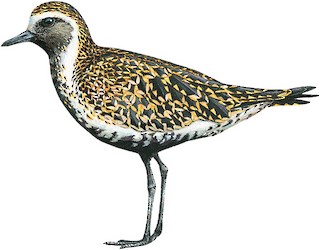

26–29 cm; 140–312 g (1); wingspan 67–76 cm. Largest and bulkiest of golden plovers , with underwing white, as opposed to brownish grey; also differs in shape and plumage colour; wings equal in length to tail or slightly longer. Female less extensively black, with some brown markings below. Non-breeding adult lacks black on face and underparts; upperparts less distinctly spotted with yellow, can turn greyish. Juvenile as non-breeding adult, with faint grey fringes on flanks and belly. In race <em>altifrons</em> male more uniformly black below, whereas nominate male has cheeks, throat, breast and belly infused with white; female altifrons has yellowish cheeks with black marks, whereas nominate female very variable, can have very pale head, but is sometimes virtually identical to male.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Owing to considerable variation within local populations and no apparent differences in measurements, validity of subspecific division regularly debated. Birds of British Is to N Germany formerly considered a separate race, oreophilos. Two subspecies normally recognized.Subspecies

Winters from British Is through Mediterranean to S Caspian Sea.

Pluvialis apricaria altifrons Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Pluvialis apricaria altifrons (Brehm, 1831)

Definitions

- PLUVIALIS

- pluvialis

- apricaria / apricarius

- altifrons

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Pluvialis apricaria apricaria Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Pluvialis apricaria apricaria (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- PLUVIALIS

- pluvialis

- apricaria / apricarius

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

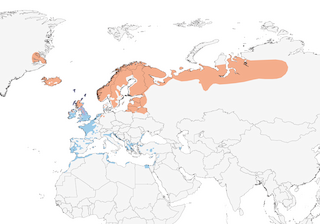

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Race altifrons breeds in humid moss, moss-and-lichen and hummock tundra , shrub tundra, open bogs in forest tundra and alpine tundra; nominate race breeds on highland heaths and peatlands. Breeds up to c. 1200 m. On migration and in winter , occurs on pastures and open agricultural land, such as stubble and fallow fields, preferring larger open areas (2), and regularly feeds on intertidal flats. Often roosts on ploughed land or amongst low crops, increasingly using arable farmland, over pastures, in E England in recent decades (3); sometimes roosts on flats and saltmarshes in shallow bays and estuaries, and has recently joined Vanellus vanellus (with which it frequently associates outside breeding season) in using large roof spaces for roosting in parts of N England (4).

Movement

Migratory, but only partially so in Britain and Ireland, and also well known for cold spell-induced movements; of seven individuals breeding in Scandinavia tracked using geolocators, three spent the winter in NW Europe and the other four left NW Europe to spend the rest of the winter in Iberia or Morocco (one that was tracked during two migration cycles moved to Iberia in the first winter but remained in NW Europe during the second), with the four winter departures all associated with a cold spell in NW Europe (5). Icelandic population leaves late Sept to early Nov, probably wintering mainly in Ireland, and in W Britain, W France and Iberia; birds from Scandinavia to Siberia winter from Britain and Netherlands to N African fringe, but mainly in S Britain, France, Iberia and Maghreb; birds from Taymyr possibly fly across W Siberia and Kazakhstan and also S along R Yenisey across taiga, towards Caspian Sea and Mediterranean, irregularly reaching as far S as Macaronesia, Mauritania and Senegambia (occurrence elsewhere in W Africa unproven) (6, 7), as well as the Middle East (to Saudi Arabia and Oman) (8). Occasionally overshoots breeding areas in spring, to reach Spitsbergen, Jan Mayen and Bear I. Adults leave breeding areas late Jul to early Sept, juveniles Oct–Nov. N extremes of wintering distribution vacated as soon as frost starts, but soon reoccupied as weather improves, with evidence for earlier arrivals in N Norway over last half-century (9). Ringing recoveries suggest more E route during return migration. In Netherlands and W Germany numbers grow in Apr and early May, and breeding areas reoccupied in May or early Jun on N tundra. In Britain, birds do not generally move far from breeding areas, which are abandoned Jul–Feb. Exceptional vagrant to S & E Asia (Indian Subcontinent (10), at L Baikal (11), as well as in China (12) and Japan) (13, 14) and North America (in Atlantic Canada and Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, especially in spring, in SE Alaska in winter and in autumn in Maine and Delaware) (15).

Diet and Foraging

Mainly invertebrate prey, especially beetles (including pupae and larvae) and earthworms; sometimes plant material, e.g. berries, seeds and grass; all kinds of insects and their larvae, spiders, millipedes and snails; on intertidal flats polychaete worms. In N England, diet of younger chicks, assessed by dry weight of prey, comprised c. 30% each of adult and larval tipulids, whereas for chicks older than 16 days, c. 70% was tipulid larvae, while beetles, spiders and caterpillars each comprised 5–20% of diet, depending on age, with older chicks taking larger prey (16). Pecks from surface or probes up to 1–2 cm; evidently also detects prey by sound. Sometimes feeds at night, irrespective of moon phase (17); for example, in N England off-duty incubating birds commute to feed on fields, females by day and males at night, with adults flying 6·6–7·2 km from nest to feed in daylight hours, while at night they commute 2·4–2·7 km (18). Moves in flocks of tens to 1000s; during breeding, flocks are smaller. During breeding season, Dunlins (Calidris alpina) often mix with off-duty birds, benefiting from vigilance of present species.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Most-frequently heard call away from breeding grounds a mellow, drawn-out, pure whistle, “puuuu”, on same pitch and monosyllabic, or similar but preceded by a short higher-pitched first syllable, “tle-oooo”. Several other variants, distinguished by differences in first syllable, varying length, etc., but typically lacks under-slurred modulation of P. squatarola. On breeding grounds, song during butterfly-like display flight (given most frequently during pair formation but continues until late Jul) a repeated plaintive double piping note, “puuuu-wheeeuw... puuuu-wheeeuw…”, the second note drawn-out and over-slurred. Also a much faster rhythmic “rut-wee-ooo....rut-wee-ooo…”.

Breeding

Lays late Mar to mid May in Britain, mid May to late Jul further N; also generally earlier at lower altitudes. Monogamous, with lifelong pair-bond, although three confirmed cases of polyandry recorded in Scotland (19). Solitary, with nests sometimes only few hundred metres apart; 1–4 pairs/km in linear survey, and 2–10·9 pairs/km² in Taymyr, but very variable between years and just 0·2 pairs/km² on Yamal Peninsula (20); in Britain, up to 16 pairs/km² on fertile soil and 0·1–0·5 pairs/km² in montane zone; in lower alpine zone of Sweden, mean 3–4 pairs/km² (21); strong breeding-site fidelity and natal philopatry. Territorial; adults feed mostly outside territory. Breeds in flat and openly vegetated areas , strongly selecting against slopes and sometimes favouring heather burnt within two years (versus older stands) (22). Nest a shallow scrape (12–14 cm wide by 3–5 cm deep), constructed by male, variably lined with moss and plant material. Usually four eggs, occasionally three , two or five, laid at intervals of 48–60 hours, colour greenish olive, red-brown or cream heavily marked with red or black-brown, mean size 52·1 mm × 35·5 mm (23); incubation 27–31 days; chick has mottled black and bright yellow upperparts, whitish underparts; fledging 25–33 days, but 34–42 days in N England (24); young independent soon after fledging. Hatching success 81% in Lapland, with a mean 0·57 fledglings/pair raised in N England (success depressed by chick starvation or exposure, rather than predators) (25). Many broods subject to predation, with stoats (Mustela erminea) responsible for many losses in NE England (22). Breeds first at two years old. Oldest ringed bird 12 years, two months. Some evidence that timing of breeding in western birds may have advanced in recent years: primary moult scores of adults staging post-breeding in pastures in The Netherlands during 1978–2011 showed no changes until 1990, but primary moult advanced by eight days between 1990 to 2011; the species starts to moult during breeding and it is suggested that advancement of moult marks an earlier start to breeding (26).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Breeding population of race apricaria estimated at 1,800,000 birds (1994), and is declining; no overall population estimates available for race altifrons, but range in Russia has been expanding in recent years and > 89,000 individuals were recently estimated to be present in S Iceland during breeding season (27), where perhaps 200,000–300,000 pairs throughout the island in late 1980s. In W Europe c. 609,000 breeding pairs, with 300,000 in Iceland (1985), 130,000 in Norway (1981), 50,000–80,000 in Finland (late 1980s) and 50,000–75,000 in Sweden (late 1980s). Contraction of S limit of range in NW Europe since mid-19th century, mainly due to habitat changes, notably cultivation and afforestation of heathland, but climate change is now seen as a new threat (28): numbers have decreased in Ireland and Britain , with 22,600 pairs in 1987; breeders from former range of Belgium to Denmark to Poland have practically disappeared (29), with scarcely ten pairs in Denmark by mid 1990s and similar numbers in Germany in 2005–2009 (30); in Norway recovered somewhat after decline in late 19th and early 20th centuries; in S Sweden decreased dramatically since mid-20th century, possibly due to climatic amelioration, but some recovery now in Sweden; major increase in Finland from 26,000 pairs in 1950s to 258,000 pairs in 1973–1976, but apparently followed by more recent decrease. Until 1950s, large numbers, probably up to 80,000 birds per year, caught in Netherlands by specialized plover-netting. Also frequently taken by hunters on wintering grounds, especially in France. Counts of Dutch wintering birds suggest marked decrease in population since 1978; maximum numbers present in winter, up to 250,000 birds in Britain (31) (85,000 in 1992, 144,000 in late 1990s) (32, 33), 400,000 in Netherlands (1978), 200,000 in Denmark, and 170,000 in Germany.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding