Common Snipe Gallinago gallinago Scientific name definitions

Text last updated August 31, 2015

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Shapka e ujit |

| Arabic | شنقب شائع |

| Armenian | Մորակտցար |

| Asturian | Gacha comñn |

| Azerbaijani | Adi tənbəlcüllüt |

| Basque | Istingor arrunta |

| Bulgarian | Средна бекасина |

| Catalan | becadell comú |

| Chinese | 田鷸 |

| Chinese (Hong Kong SAR China) | 扇尾沙錐 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 扇尾沙锥 |

| Croatian | šljuka kokošica |

| Czech | bekasina otavní |

| Danish | Dobbeltbekkasin |

| Dutch | Watersnip |

| English | Common Snipe |

| English (United States) | Common Snipe |

| Faroese | Mýrisnípa |

| Finnish | taivaanvuohi |

| French | Bécassine des marais |

| French (France) | Bécassine des marais |

| French (Haiti) | Bécassine des marais |

| Galician | Aguaneta común |

| German | Bekassine |

| Greek | (Κοινό) Μπεκατσίνι |

| Hebrew | חרטומית ביצות |

| Hungarian | Sárszalonka |

| Icelandic | Hrossagaukur |

| Indonesian | Berkik ekor-kipas |

| Italian | Beccaccino |

| Japanese | タシギ |

| Korean | 꺅도요 |

| Latvian | Mērkaziņa |

| Lithuanian | Perkūno oželis |

| Malayalam | വിശറിവാലൻ ചുണ്ടൻകാട |

| Marathi | सामान्य पाणलावा |

| Mongolian | Шөвгөн хараалж |

| Norwegian | enkeltbekkasin |

| Persian | پاشلک معمولی |

| Polish | kszyk |

| Portuguese (Brazil) | Common Snipe |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Narceja |

| Romanian | Becațină comună |

| Russian | Бекас |

| Serbian | Barska šljuka |

| Slovak | močiarnica mekotavá |

| Slovenian | Kozica |

| Spanish | Agachadiza Común |

| Spanish (Spain) | Agachadiza común |

| Swedish | enkelbeckasin |

| Thai | นกปากซ่อมหางพัด |

| Turkish | Suçulluğu |

| Ukrainian | Баранець звичайний |

Gallinago gallinago (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- GALLINAGO

- gallinago

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

25–27 cm; 72–181 g; wingspan 44–47 cm. Small to medium-sized snipe , with rather long bill and white belly; plumage variable, and melanistic morph occurs (e.g. in Ireland); flight generally faster and more erratic than other snipes of similar size. Differs from very similar but wholly allopatric G. paraguaiae normally by neck, breast and flanks more heavily marked, and, in flight, wings more pointed; from G. stenura, G. hardwickii and G. megala by prominent white trailing edge to wing, and supercilium narrower than eyestripe at base of bill. Separation from very similar, and formerly conspecific, G. delicata potentially very difficult and will require prolonged and detailed views to establish a vagrant of either species within the range of the other; see G. delicata. Sexes alike, differing only in measurements of body and feathers, especially total length of outer tail feather. No significant seasonal variation. Juvenile very similar to adult , but wing-coverts more neatly but narrowly fringed pale buff (versus more prominent oval spots, separated by a dark shaft-streak in adults), rectrices lack dark shaft-streak distally, secondaries and tertials have narrower white tips, edges to outer edge of scapulars also white (yellowish and broader in adults) and primaries worn (fresh in adults); ageing impossible following post-juvenile moult (1). Race faeroeensis darker and more rufous above, with narrower, less contrasting, back stripes.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Until recently, considered conspecific with G. delicata. Also sometimes lumped with G. nigripennis, G. paraguaiae and G. andina, but differences in size, outer tail feathers and quality of aerial “winnowing” suggest separate species status; G. macrodactyla may also be close relative. Has hybridized with G. media (2). Two subspecies currently recognized.

Subspecies

Gallinago gallinago faeroeensis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Gallinago gallinago faeroeensis (Brehm, 1831)

Definitions

- GALLINAGO

- gallinago

- faeroeensis / faeroensis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Gallinago gallinago gallinago Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Gallinago gallinago gallinago (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- GALLINAGO

- gallinago

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Great x Common Snipe (hybrid) Gallinago media x gallinago

Distribution

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Open fresh or brackish marshland with rich or tussocky vegetation, grassy or marshy edges of lakes and rivers, wet hay fields, swampy meadows and marshy tundra, in forest tundra and northernmost taiga zones; in general, found in areas providing combination of grassy cover and moist soils , rich in organic matter, and prefers relatively heterogeneous vegetation structure at breeding sites (3). On Yamal Peninsula, N Russia, snipes reach highest densities in lowland flooded tundra (4), while in S Iceland, wetlands are the most important habitat type during the breeding season (5). Outside breeding season, generally occupies similar habitats, with more use of anthropogenic habitats, e.g. sewage farms and rice fields; also upper reaches of estuaries , sometimes on coastal meadows. Recorded to at least 2800 m in Himalayas (6).

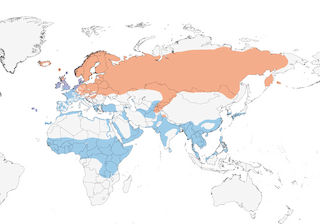

Movement

Mostly migratory, wintering S to N tropics; some populations sedentary or partially migratory, e.g. British Is (which also receives visitors from further N & E in winter, as well as race faeroeensis) (7), with small numbers also wintering as far N as Iceland, Faeroes, W Norway, Denmark and W Germany (8). Race faeroeensis moves S to Ireland and westernmost Britain, S to Scilly, in winter (with passage of Icelandic birds through Orkney, Shetland and Outer Hebrides also suspected) (7). Analysis of snipe ringed in Poland revealed that birds migrating along Baltic coast tend to winter further N than those that pass through S Poland on migration, while snipe moving through the country at the beginning of autumn migration (originating from near breeding areas) overwinter further N than later migrants (from more northern areas), i.e. a leap-frog migration pattern (9). Moves quickly from breeding grounds to moulting areas, and after few weeks quickly migrates to wintering grounds. High degree of site fidelity at staging sites and at least some evidence that individuals re-use same wintering areas (10). Birds wintering in Afrotropics presumably from Russia, crossing Sahara on broad front. European and Atlantic birds move to S & W Europe; species seems to have shifted main moulting grounds from continental (particularly Netherlands) to Britain since late 1950s. Autumn passage from late Jul to Nov, with arrival in N Africa mainly late Sept to early Oct, S of Sahara mainly Oct to early Nov; most birds leave Africa in Mar; crosses Europe Mar to early May, males typically arriving on breeding grounds 10–14 days earlier than females; detailed study of spring migration across N Poland found that numbers at five sites peaked in first and second weeks of Apr (11), while investigation of autumn passage through C Europe has found that it has become later over the last c. 40 years, presumably in response to climate change (12). Vagrant to Spitsbergen, Bear I, Jan Mayen and Mauritania (8), as well as on Palau (Feb 2003) and Yap (Nov 2008) in Micronesia (13), and in the New World in Newfoundland (Feb 2011) and California (Dec 2011), while the species is fairly common to rare in spring on W Aleutians (much less common on C Aleutians, Pribilofs and St Lawrence) (14).

Diet and Foraging

Diet includes larval insects (10–80%), adult insects, earthworms , small crustaceans, small gastropods and spiders; plant fibres and seeds consumed in smaller quantities, once of teasel (Dipsacus fulonum) (15), whose seeds are rarely exploited by birds. In NE England, diet during Apr–Jun consisted mainly of earthworms and tipulid larvae, which accounted for 61 ± 7% and 24 ± 6% of dry weight of prey items ingested, respectively, but a wide variety of surface-active and aquatic prey were also taken, especially in Apr (16). Feeds by vertical, rhythmic probing in substrate, often without removing bill from soil. Feeds typically in small groups, although may exhibit antagonistic behaviour towards conspecifics (17); essentially crepuscular.

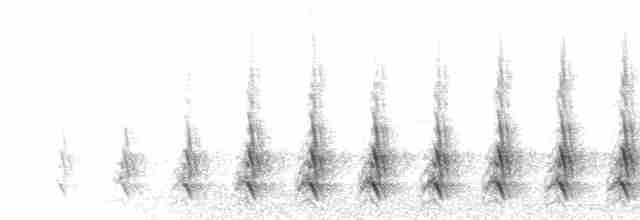

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Male's "winnowing" song (drumming) is a slightly accelerating and rising “w-w-w-w-w-w-w-w-w-w” or “huhuhuhuhuhuhuhuhuhu”, lasting between 1·5 and two seconds, given during display flight (produced by airflow over outstretched outermost rectrix either side of spread tail, modulated by beating of wing), which commences with wide curve over 80–120 m rising at angle of c. 10º, before increasing angle of ascent to 30º, reaching c. 50 m above ground, before diving down at 40–45º (during which drumming sound is produced), then pulls out into brief glide, whereupon the process is repeated. Most frequently heard call , often in rapid escape flight or migratory flights at night, given either singly or in rapid series, is a hoarse or grating “schkape” or sightly more disyllabic “ska-ip”; also heard during pursuit flights. Also heard are a hard, sharp “djugg”, often given in extended series, both on ground or in flight, by either sex, during breeding season, as well as a yakking, clockwork-like “CHIP-per-CHIP-per-CHIP-per...”, with a hollow quality and also often given for prolonged periods, most frequently given at dawn and dusk both before and after drumming flights, but also during day or by night (if moonlit).

Breeding

Laying Apr–Jun (later at higher latitudes), exceptionally Mar (18). Monogamous, but both sexes show high degree of promiscuity. Pairs occasionally form on passage, but generally males arrive on breeding grounds 10–14 days before females (8). Territorial; densities up to 10–38 (even 110) pairs/km². Nest (constructed by female) (18) usually on dry spot, covered by grasses, rushes, sedges or sphagnum, lined with fine grasses, scrape 10–15 cm wide and 2–5 cm deep (8). Typically single-brooded (8), exceptionally double-brooded (18). Four eggs (2–5), with laying interval one day, pale green to olive or darker buff, blotched blackish to red-brown, violet or grey, mean size 39·3 mm × 28·6 mm (18); lays replacement clutches; incubation 17–21 days (8), by female alone, starting with third or fourth egg (18); chick mahogany red, more hazel-brown or tawny on sides of head and underparts, with black and white bands on head; both parents care for young, but male entices oldest 1–2 from nest to tend; young initially fed bill-to-bill; fledging 19–20 days. Success 2·2 hatchlings per nest, 3·5 per successful nest. High proportion of eggs may be predated or trampled by cattle. Mean annual mortality 52%.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Global population recently estimated at more than 4,000,000 birds (19), but that in Europe numbers 2,670,000–5,060,000 pairs (2000–2014), with 2,000,000–4,000,000 pairs (77%) in W Russia alone, where breeding range is reportedly extending N in recent decades (8, 20); possibly more than 1,000,000 birds winter in SW & SC Asia, and 100,000s in E & SE Asia. Elsewhere, in Europe, some 92,000–180,000 pairs nest in Finland, 72,000–197,000 in Sweden, 70,000–90,000 in Belarus, and 80,000 pairs in UK (20). Westernmost outpost is Azores, where seven islands support breeding populations and densities of up to 6·8–8·5 breeding pairs per km² have been reported; despite reasonably common presence of G. delicata in non-breeding season (21), there is no evidence to date that the latter breeds in the archipelago (22). Total of 180,000 pairs (faroeensis) breed in Iceland, with perhaps c. 105,000 individuals in S of island (5) (versus 200,000–300,000 pairs in late 1980s), with another 800–2000 pairs in Faeroes (8). Common to very abundant on African wintering grounds (c. 1,500,000 in Sudan). Decline noted in many breeding populations of Europe (e.g. 30% decrease in Northern Ireland between 1987 and 1999 (23), and French population most recently estimated at just 37–62 pairs) (24) and W Siberia (though has apparently colonized Slovenia (25) and numbers reportedly stable in Norway, Estonia, Hungary, Spain, Croatia and Russia) (8), probably chiefly due to habitat changes, especially drainage; in Schleswig-Holstein, N Germany, decline from 13,000 pairs in 1970 to 1500 in 1992, and total population in Germany most recently estimated at 5500–8500 pairs (26); 99–100% decline after improvement of marginal grasslands in N England, where mean breeding density on moorlands was 2·28 ± 0·25 birds/km² during surveys in early part of present century (16), and overall decline of 67% across the British Isles during final quarter of 20th century, despite significant local increases (27). Beyond S edge of breeding range, formerly nested in Armenia and Bulgaria (8), probably breeds in parts of Turkey (28), and there are summer records from Azerbaijan (8). Low water levels shorten period of food availability in pastures, due to lower penetrability of soil, and thereby strongly influence length of breeding season; careful manipulation of water levels may allow improvement of breeding success, but general habitat management designed to improve conditions for grassland-breeding waders often leads to only short-term gains for present species (29) and it is now generally believed that declines are probably not exclusively driven by changes in habitat conditions (27), although increases have been registered on former grouse moors after management was discontinued (30). Changes in habitat structure and food abundance, which already negatively affect this (and many other) species might also lead to increased predation risks for nestlings (31). Estimated 1,500,000 birds hunted annually in Europe (notably France).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding