Common Buzzard Buteo buteo Scientific name definitions

Revision Notes

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Bruinjakkalsvoël |

| Albanian | Huta |

| Arabic | حوام شائع |

| Armenian | Մեծ ճուռակ |

| Asturian | Buzacu comñn |

| Azerbaijani | Adi sar |

| Basque | Zapelatz arrunta |

| Bulgarian | Обикновен мишелов |

| Catalan | aligot comú |

| Chinese | 歐亞鵟 |

| Chinese (SIM) | 欧亚鵟 |

| Croatian | škanjac |

| Czech | káně lesní |

| Danish | Musvåge |

| Dutch | Buizerd |

| English | Common Buzzard |

| English (United States) | Common Buzzard |

| Faroese | Músvákur |

| Finnish | hiirihaukka |

| French | Buse variable |

| French (France) | Buse variable |

| Galician | Miñato común |

| German | Mäusebussard |

| Greek | (Κοινή) Γερακίνα |

| Hebrew | עקב חורף |

| Hungarian | Egerészölyv |

| Icelandic | Músvákur |

| Italian | Poiana |

| Japanese | ヨーロッパノスリ |

| Korean | 대륙말똥가리 |

| Latvian | Peļu klijāns |

| Lithuanian | Paprastasis suopis |

| Malayalam | പുൽപ്പരുന്ത് |

| Mongolian | Ойн сар |

| Norwegian | musvåk |

| Persian | سارگپه معمولی |

| Polish | myszołów |

| Portuguese (Angola) | Bútio-comum |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Águia-d'asa-redonda |

| Portuguese (RAA) | Águia-d'asa-redonda |

| Portuguese (RAM) | Manta |

| Romanian | Șorecar comun |

| Russian | Канюк |

| Serbian | Mišar |

| Slovak | myšiak hôrny |

| Slovenian | Kanja |

| Spanish | Busardo Ratonero |

| Spanish (Spain) | Busardo ratonero |

| Swedish | ormvråk |

| Thai | เหยี่ยวทะเลทรายตะวันตก |

| Turkish | Şahin |

| Ukrainian | Канюк звичайний |

Revision Notes

Nárgila Moura, Shawn M. Billerman, and Paul G. Rodewald revised the account and standardized the content with Clements taxonomy. Peter Pyle contributed to the Plumages, Molts, and Structure page.

Buteo buteo (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- BUTEO

- buteo

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

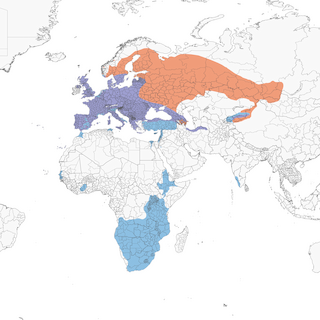

The Common Buzzard is a compact, medium-sized raptor that is widespread in the Palearctic, where it breeds from Atlantic islands (Canary, Azores, and Cape Verde Islands), across most of Europe to south-central Russia, and south to northwestern China and northern Iran. Its overwintering range includes the western Palearctic, eastern and southern Africa, and the Indian subcontinent. The species has highly variable plumage (among individuals and subspecies) and is therefore often confused with other raptors, such as European Honey-buzzard (Pernis apivorus), Rough-legged Hawk (Buteo lagopus), and Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufinus). It is often encountered soaring for longer periods over open ground, but is also associated with woodland habitats. The Common Buzzard is an opportunistic predator, adapting its diet according to local and seasonal availability, with rabbits and rodents being typical prey, but it also frequently takes birds and other vertebrates, and is often encountered foraging on the ground for large insects or earthworms. In lowland areas, it typically nests in woodlands whilst in highland areas often nests on cliffs. Insular subspecies are resident whilst mainland population can be resident, partial or full migrants of either short or long-distances.

Field Identification

A medium-sized raptor (length 40‒52 cm), compact, short-headed with a thick neck coupled with broad rounded wings and tail. The plumage is extremely variable but is generally dark brown above and on most of underbody and underwing coverts; from below, wingtip and trailing edge of wing dark, flight feathers barred, pale area in outer primaries.

Similar Species

Data from Cramp and Simmons (1) and Walls and Kenward (2).

Easily confused with the European Honey-buzzard (Pernis apivorus) which has a weaker bill, longer more protruding neck, longer wings and longer and fuller tail. Has very different soaring silhouettes in holding its wings flat or slightly drooped, whilst Common Buzzard soars with wings generally slightly raised (but also can be held flat). The resemblance between both species has been considered a case of mimicry in which juvenile European Honey-buzzard has evolved to mimic Common Buzzard and therefore is less prone to predation by Eurasian Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) (3).

Rough-legged Hawk (Buteo lagopus) is a little larger and longer winged with usually prominent dark carpals and pale uppertail. Can recall some individuals of the Common Buzzard subspecies vulpinus/menetriesi (Steppe Buzzard), but Rough-legged Hawk has a paler head and darker belly and lacks the fine bars on the under tail and also hovers persistently.

The Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufinus) is easily confused with the subspecies vulpinus, but the Long-legged Buzzard is considerably larger with longer wings and more eagle-like proportions with more contrast between the dark belly and pale breast, also the primaries and tail are more translucent.

In the dark morph of Booted Eagle (Hieraaetus pennatus), the primaries and secondaries are mostly dark (apart from a few inner primaries) and not pale as in Common Buzzard; Booted Eagle also has a longer tail and soar with flat wings (not raised).

The much larger Short-toed Snake-Eagle (Circaetus gallicus) can be confused with paler morphs of the Common Buzzard at a distance, but shows a spotted underwing, long broad wings a large protruding owl-like head and a square tail.

The Western Marsh Harrier (Circus aeruginosus) can look similar from a distance, but the harrier in flight holds a more distinguished V-shape than the Common Buzzard.

Plumages

Common Buzzard has 10 functional primaries (numbered distally, from innermost p1 to outermost p10), usually 15 secondaries (numbered proximally, from innermost s1 to outermost s12 and including three tertials numbered distally, from t1 to t3), and 12 rectrices (numbered distally on each side of the tail from innermost r1 to outermost r6). Accipitrine hawks are diastataxic (see 4) indicating that a secondary has been lost evolutionarily between what we now term s4 and s5. Wings are broad and rounded (wing morphology usually p7 > p8 ~ p6 > p9 > p5 > p4 > p10 > p3 and with p8‒p10 notched and p5‒p9 emarginated; 1); tail is squared. Geographic variation in appearance and molt strategies slight to moderate; see Systematics: Geographic Variation for differences among populations. See Molts for molt and plumage terminology. Following based primarily on plumage descriptions in Cramp and Simmons (1), Forsman (5, 6), and images in the Macaulay Library; see these references and Broekhuysen and Siegfried (7), Baker (8) and Zuberogoitia et al. (9) for ageing and sexing criteria for Common Buzzard, and Pyle (10) for criteria of similar Buteo species.

Common Buzzard exhibits polymorphism, with morphs often grouped in 3 categories based primarily on coloration of underparts, pale, intermediate, and dark, with intermediate the most common. However, variation is almost continuous from lightest to darkest individuals, making the morph categories convenient but somewhat arbitrary. Sexes generally similar in appearance; definitive appearance is usually assumed at the Third Basic Plumage, occasionally the Fourth Basic Plumage.

Natal Down

Present primarily June‒August. Hatchlings covered with thick white protoptile (first) down at birth, white to brownish gray with white nape patch and darker around eye; mesoptile (second) down shorter and of same color (1).

Juvenile (First Basic) Plumage

Present primarily September‒May. Similar to Definitive Basic Plumage except underparts longitudinally streaked or spotted as opposed to barred; rectrices and to a lesser extent secondaries with more distinct barring and the dark subterminal bar about the same width as other bars. Primaries, secondaries, and rectrices are uniform in wear and narrower than basic feathers, not showing mixed generations of remiges or molt clines (see Definitive Basic Plumage). Morphs are similar in flight-feather characters; but differ in the density of streaking to the underparts, from little or no streaking in the palest individuals to dense streaking in the darkest individuals.

Formative Plumage

A Preformative ("Post-juvenile") Molt of scattered body feathers in December‒March, prior to commencement of the Second Molt, is unrecorded (9) but possibly may exist in some Common Buzzards, as occurs in other Accipitrid and Buteo hawks (11). Formative feathers may occur at scattered locations on upperprats and breast and would be fresher and intermediate in appearance between those of Juvenile and Definitive Basic plumages, the feathers of chest perhaps with tear-drop or bar-like markings. Uniformly juvenile wing and tail feathers are retained.

Second and Third Basic Plumages

Often equated with "First Post-breeding" and "Second-Post-breeding" plumages, respectively, of life cycle terminology. Present primarily September‒August. Similar to Definitive Basic Plumage but 3‒4 juvenile outer primaries (among p7‒p10) and 1‒5 juvenile secondaries (among s3‒s4 and s7‒s10) retained during the Second Prebasic Molt, contrastingly worn, narrower and paler (more bleached) and the secondaries with even-width barring (9; see also 6, 12, 10). Look also for some birds to have retained juvenile rump feathers and rectrices in Second Basic Plumage. Occasional individuals may retain 1‒2 primaries or secondaries (among p9‒p10, s4, and s8‒s9) during the Third Prebasic Molt and be identifiable in Third Basic Plumage, but most birds in this plumage likely have replaced all juvenile remiges and become indistinguishable from birds in Definitive Basic Plumage.

Definitive Basic Plumage

Often equated with "Adult Post-breeding Plumage" of life cycle terminology. Present primarily October-September. Plumage variable. Intermediate morph most common: Crown and upperparts brown, some feathers fringed pale brown or rufous. Rectrices highly variable in pattern, grayish to rufous, usually with indistinct basal bars and with a subtermnial band that is wider and/or more distinct than the basal bars. Sides of head can be same color as crown or, often, with an indistinct paler supercilum and auriculars and darker postcular feathers among auriculars. Breast variably entirely dark brown but often whitish to buff with tear-drop shaped marks, paler lower breast and ventral region, row of dark marks are bars across abdomen, and darker flanks. Underwing coverts whitish to buff with variable dark bars or marks, the primary coverts usually tipped dark forming a crescent-shaped patagial mark. Paler morphs can have whiter sides of head with more distinct supercilium and eyeline, whiter breasts with fewer markings, and distinct abdominal band. Some subspecies can be largely rufous (see Systematics: Geographic Variation). Darker morphs are blacker above and can vary to showing entirely blackish plumage with indistinct pale barring to flight feathers.

Following incomplete molts remiges can show 2‒4 sets of feathers in Staffelmauser (or stepwise) patterns (see Molts), the number of sets signifying minimum age (see 5, 6, 12, 13, 10, 9).

Molts

General

Molt and plumage terminology follows Humphrey and Parkes (14), as modified by Howell et al. (15). Under this nomenclature, terminology is based on evolution of molts along ancestral lineages of birds from ecdysis (molts) of reptiles, rather than on molts relative to breeding season, location, or time of the year, the latter generally referred to as “life-cycle” molt terminology (16; see also 17). In north-temperate latitudes and among passerines, the Humphrey-Parkes (H-P) and life-cycle nomenclatures correspond to some extent but terms are not synonyms due to the differing bases of definition. Prebasic molts often correspond to “post-breeding“ or “post-nuptial“ molts (the Second Prebasic Molt often equating to the "first post-breeding molt," etc.) and preformative molts often correspond to “post-juvenile“ molts. The terms prejuvenile molt and juvenile plumage are preserved under H-P terminology (considered synonyms of first prebasic molt and first basic plumage, respectively) and the former terms do correspond with those in life-cycle terminology.

Is in other Buteo hawks, Common Buzzard appears to exhibit a Complex Basic Strategy (cf. 15, 18), including incomplete-to-complete prebasic molts and a limited preformative molt (11), but no prealternate molts (7, 1, 6, 9, 10).

Prejuvenile (First Prebasic) Molt

Complete, primarily May–August, in the nest. No detailed information on this molt in Common Buzzard. In similar Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) of North America, primary sheaths begin erupting at 13–15 d, primaries and secondaries at 17–19 d, and rectrices at 21–23 d. At 29–31 d, head is 90% downy (white occipital spot evident), dorsal wing is 90% feathered, and breast is 50% feathered; legs beginning to feather, upper tail coverts are well-developed. By 33–35 d, head is 50% feathered, dorsal body feathering is 95% complete, and breast is 90% feathered. Juvenile plumage well developed at time of first flight.

Preformative Molt

Only recently recognized in Buteo hawks as separate from commencement of the Second Prebasic Molt (11); in Common Buzzard, this molt has not been confirmed (7,9), but a limited molt appears to occur in some (but not all) individuals in November–March (cf. 1, 5) as occurs in Red-tailed Hawk (11, 10). In that species, the Preformative Molt can include up to 40% of body feathers and is absent in some individuals; based on examination of Macaulay Library images it appears to occur less frequently and less extensively in Common Buzzard (P. Pyle, unpublished data). No wing coverts or flight feathers replaced during Preformative Molts in other Buteo hawks.

Second Prebasic and Third Prebasic Molts

Incomplete (to possibly complete), primarily May–October in the Northern Hemisphere but can extend into winter months for birds migrating to southern Africa (7). Replacement of juvenile body feathers and rectrices often complete but some rump and scattered other body feathers, upperwing coverts, and or rectrices (among r2 and r5) may sometimes be retained, as in other Buteo hawks. Sequence of flight-feather replacement as in Definitive Prebasic Molt but outer 1–5 (often 3–4) juvenile primaries (among p6–p10) and corresponding primary coverts, 1–6 juvenile secondaries (among s3–s4 and s6–s9) are typically retained, to commence Staffelmauser (stepwise) replacement patterns (19, 12, 13, 10). Third Prebasic Molt commences where Second Prebasic Molt arrested and new sequences can commence at p1, the tertials, s1, and s5 prior to replacement of all juvenile feathers. Occasionally 1–2 outer primaries (among p9–p10) or 3–4 juvenile secondaries (among s3–s4 or s8–s9) may be retained following the Third Prebasic Molt, as occurs in other large Accipitrid raptors. See images under Plumages.

Definitive Prebasic Molt

Incomplete to complete, primarily April–October in the Northern Hemisphere but can extend into winter months for birds migrating to southern Africa (7). Molt may sometimes commence with one to a few remiges during incubation (especially in females), suspend for chick feeding, and resume following chick fledging as in other diurnal raptors (12); study needed in Common Buzzard. Primaries are replaced distally (p1 to p10), secondaries replaced proximally from s1 and s5 and distally from the tertials (often bilaterally from the middle tertial, t2) , and rectrices may typically be replaced in sequence r1–r6–r3–r4–r2–r5 on each side of tail. Molt pattern among primaries and secondaries exhibits Staffelmauser (19, 20, 12, 13, 10) whereby incomplete molts result is a series of commencement points, beginning with termination points of previous prebasic molt and also initiating new series commencing at p1, s1, s5, and/or the tertials. Replacement thus typically proceeds in 2–4 (rarely 1 or 5) waves through the wing. Staffelmauser appears to be a product of insufficient time to undergo a complete wing-feather molt but has adaptive benefits in producing multiple small gaps in the wing during molt, which retains wing integrity and ability to fly and forage (21, 22, 12).

Bare Parts

From Cramp and Simmons (1):

Bill and Cere

In adults, bill horn-black, tinged blue at base; cere yellow. In nestlings, cere pinkish, rapidly becoming yellow.

Iris

In adults, iris color variable, from dark brown to brownish yellow to yellow or occasionally whitish; appears to be related somewhat to plumage morph, averaging paler and grayer in pale morph and darker and browner in dark morph. Iris averages paler in juvenile than adult, probably changing gradually over first year as occurs in other Buteo hawks.

Tarsi and Toes

Legs and feet are yellow (paler in nestling and juvenile); claws are horn, paler or darker related to corresponding plumage morphs.

Measurements

Linear Measurement

Data from Cramp and Simmons (1).

Wing length

- B. b. buteo male 368‒404 mm (mean 387 mm, n = 42); female 374‒419 mm (mean 398 mm, n = 39)

- B. b vulpinus and B. b. menetriesi combined male 341‒387 mm (mean 360 mm, n = 27); female 352‒400 mm (mean 375 mm, n = 38)

- B. b. insularum male 352‒389 mm (mean 371 mm, n = 7); female 370‒380 mm (mean 376, n = 4)

- B. b. bannermani female 375‒385 mm (mean 380 mm, n = 2)

- B. b. rothschildi male 343‒365 mm (mean 352 mm, n = 13); female 362‒380 mm (mean 369 mm, n = 10)

- B. b. arrigonii male 343‒382 mm (mean 360 mm, n = 20); female 352‒380 mm (mean 370 mm, n = 18)

- B. b. menetriesi male 370‒385 mm (mean 377 mm, n = 15); female 390‒413 mm (mean 396 mm, n = 12)

Tail length

- B. b. buteo male 194‒223 mm (mean 387 mm, n = 42); female 193‒234 mm (mean 215 mm, n = 39)

- B. b vulpinus and B. b. menetriesi combined male 174‒207 mm (mean 189 mm, n = 28); female 178‒210 mm (mean 192 mm; n = 19)

Bill length

- B. b. buteo male 20‒23.6 mm (mean 21.6 mm, n = 41); female 19.3‒24.9 mm (mean 23 mm, n = 37)

- B. b vulpinus and B. b. menetriesi combined male 18.8‒22 mm (mean 20.4 mm, n = 27); female 19.2‒24.1 mm (mean 22 mm, n = 21)

Tarsus length

- B. b. buteo male 69‒80 mm (mean 75 mm, n = 26); female 72.5‒83 mm (mean 76.5 mm, n = 27)

- B. b vulpinus and B. b. menetriesi combined male 70‒75 mm (mean 72 mm; n = 14); female 71‒79 mm (mean 74 mm, n = 13)

Mass

B. b. buteo

- Februrary‒March male 525‒980 g (mean 762 g, n = 76); female 625‒1,176 g (mean 915 g, n = 92)

- April‒May male 552‒846 g (mean 732 g, n = 17); female 486‒1,197 g (mean 881 g, n = 19)

- June‒July male 600‒813 g (mean 692 g, n = 10); female 727‒946 g (mean 865 g, n = 5)

- August‒September male 427‒850 g (mean 706 g, n = 11); female 800‒988 g (mean 911 g, n = 15)

- October‒November male 620‒985 g (mean 828 g, n = 24); female 710‒1,327 g (mean 1,052 g, n = 48)

- December‒January male 620‒1,183 g (mean 818 g, n = 76); female 770‒1,364 g (mean 1,018 g, n = 82)

Systematics History

Taxon bannermani of the Cape Verde Islands has a complex taxonomic history, where it is sometimes treated as specifically distinct from Buteo buteo, as conspecific with Buteo buteo, as here, or as a subspecies of Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufinus). The Cape Verde Islands were likely colonized during the Pleistocene, and perhaps prior to the split of Mountain Buzzard (Buteo oreophilus) (23). Hartert (24) and, much later, Vaurie (25), James (26), and Ferguson-Lees and Christie (27) all considered bannermani too similar in morphology to nominate Buteo buteo to even recognize as a subspecies, and Bannerman (28) noted that "it is so similar in appearance to our British Buzzard." Nevertheless, major checklists such as Peters (29, 30, 31) continued to treat bannermani as a valid taxon. De Naurois (32) was first to draw attention to the apparently analogous situation of the (then unnamed) Buteo population on the island of Socotra (now Socotra Buzzard (Buteo socotraensis)), on the opposite side of Africa, at a similar latitude. Subsequently, Hazevoet (23) elected to treat bannermani as a phylogenetic species, but Snow and Perrins (33) retained it as a subspecies of Buteo buteo, as did del Hoyo and Collar (33), whereas others have treated it (and Buteo socotraensis) as a subspecies of Buteo rufinus (34); see also Related Species (below).

In addition to bannermani, the taxonomy of other Buteo taxa in Eurasia and Africa has a complicated history, and Buteo buteo has also been considered conspecific with Buteo oreophilus, Forest Buzzard (Buteo trizonatus), Madagascar Buzzard (Buteo brachypterus), and until recently also Eastern Buzzard (Buteo japonicus) and Himalayan Buzzard (Buteo refectus); it is closely related to all five, and possibly also to Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) and Rufous-tailed Hawk (Buteo ventralis). Buteo japonicus is weakly distinct morphologically from Buteo buteo and Buteo refectus (35, 36), more so vocally (36), and strongly so genetically (35). Buteo refectus (under the name burmanicus; confusion over correct name now resolved, see 37 and 34) separated from vulpinus of Buteo buteo on account of size, plumage, and vocal differences (36), and this supported by molecular evidence (35). Subspecies vulpinus may be approaching species threshold (in which case with menetriesi as a subspecies).

Geographic Variation

Extensive geographic variation, partly clinal and confounded by individual variation; subspecies separated on size, coloration, and plumage pattern. Nominate subspecies is highly variable in amount of brown, black, and white in plumage, but generally with little rufous.

Subspecies

Seven subspecies recognized here; up to 9 subspecies recognized by other authorities. Some island subspecies poorly defined and possibly better rejected; thus, rothschildi often subsumed within insularum, harterti within nominate, and arrigonii within pojana. Suggested separation of Spanish population as hispaniae (25) generally not accepted.

Common Buzzard (Western) Buteo buteo buteo Scientific name definitions

Systematics History

Falco Buteo Linnaeus, 1758, Systema Naturae 10(1):90. Type locality originally given as "Europe" but later restricted to Sweden by Hellmayr and Laubmann (38).

Distribution

Western Palearctic region and Madeira; winters to western Africa

Identification Summary

Highly variable in amount of brown, black, and white in plumage, but generally with little rufous. See Plumages.

Buteo buteo buteo (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- BUTEO

- buteo

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Common Buzzard (Corsican) Buteo buteo arrigonii Scientific name definitions

Systematics History

Buteo buteo Arrigonii Picchi, 1903, Avicula 7:40. Type locality Sardinia.

Distribution

Corsica and Sardinia.

Identification Summary

B. b. arrigonii is medium-brown above and with heavy streaking below.

Buteo buteo arrigonii Picchi, 1903

Definitions

- BUTEO

- buteo

- arrigonii

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Common Buzzard (Azores) Buteo buteo rothschildi Scientific name definitions

Systematics History

Buteo buteo rothschildi Swann, 1919, A Synoptical List of the Accipitres. Part II. pg. 43. Type locality Terceira, Azores (39).

Distribution

Azores.

Identification Summary

Medium-brown upperparts and dark-brown underparts.

Buteo buteo rothschildi Swann, 1919

Definitions

- BUTEO

- buteo

- rothschildi

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Common Buzzard (Canary Is.) Buteo buteo insularum Scientific name definitions

Systematics History

Buteo insularum Floericke, 1903, Mitteilungen des Österreichischen Reichsbundes für Vogelkunde und Vogelschutz in Wien, p. 64. Type locality listed as Grand Canaria.

Distribution

Canary Islands.

Identification Summary

Rather similar to subspecies arrigonii, but slightly larger.

Buteo buteo insularum Floericke, 1903

Definitions

- BUTEO

- buteo

- insularum

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Common Buzzard (Cape Verde) Buteo buteo bannermani Scientific name definitions

Systematics History

Buteo buteo bannermani Swann, 1919, A Synoptical List of the Accipitres, pt. 2:44.—Near Mindello Bay, Sao Vicente, Cape Verde Islands.

The holotype is an adult female, collected by D. A. Bannerman on 26 September 1913, and held at what is now at the Natural History Museum, Tring (NHMUK 1919.8.15.148) (40). Being the only record for the island (23), Robb and Pop (41) pondered whether the type specimen might have been brought from nearby Santo Antão and purchased at the port town of Mindelo on São Vicente.

Distribution

Identification Summary

Buteo buteo bannermani Swann, 1919

Definitions

- BUTEO

- buteo

- bannermani

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Common Buzzard (Steppe) Buteo buteo vulpinus/menetriesi

Distribution

Finland and European Russia east to Yenisey River, and south to northern Caucasus and central Asia (Altai, Tien Shan); overwinters mainly in eastern and southern Africa, and also southern Asia.

Identification Summary

B. b. vulpinus normally smaller, often with rusty underbody , underwing coverts and upperside of tail, generally separable from rufinus by darker head and faintly barred tail.

Buteo buteo vulpinus (Gloger, 1833)

Definitions

- BUTEO

- buteo

- vulpinus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Distribution

Southern Crimea and Caucasus south to eastern Turkey and northern Iran.

Identification Summary

Rather similar to vulpinus, but larger.

Buteo buteo menetriesi Bogdanov, 1879

Definitions

- BUTEO

- buteo

- menetriesi / menetriesii

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Related Species

The relationships of Buteo buteo are complicated, and some evidence suggests that it might not be monophyletic, with bannermani, formerly considered a distinct species (Cape Verde Buzzard, sensu lato), possibly being sister to the recently described Socotra Buzzard (Buteo socotraensis) (46), or as part of a monophyletic group with Buteo socotraensis and Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufinus) (35). Londei (47) conducted field observations on bannermani, which he believed confirmed a close relationship between this species and Buteo rufinus. Outside of bannermani, the relationships of nominate buteo are no clearer; it may be most closely related to a clade of Buteo rufinus and Upland Buzzard (Buteo hemilasius) (35), or it may be sister to Mountain Buzzard (Buteo oreophilus), with Buteo rufinus in turn sister to these two species (48). Further work is needed to clarify the relationships of these Buteo taxa.

Has hybridized with Rough-legged Hawk (Buteo lagopus) in Norway (49) and Finland (50), with Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufinus) in Strait of Gibraltar region (southern Spain) (51), and with Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) (escaped captive) (52).

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Common x Long-legged Buzzard (hybrid) Buteo buteo x rufinus

Fossil History

Information needed.

Distribution

Breeding population is widespread in the Palearctic from Atlantic islands (Canary, Azores, and Cape Verde Islands), across most of Europe, with its northern limits in central Scandinavia and northeastern Russia, extending east to south-central Russia (River Yenisey) and northwestern Mongolia, and south to Kyrgyzstan and northwestern China, northern Iran, southern Turkey, and central Israel. Overwintering range includes much of western Palearctic (north to southern Scandinavia), eastern and southern Africa, and also Indian subcontinent.

Historical Changes to the Distribution

Information needed.

Habitat

Highly variable, but almost always with some degree of tree cover that is required for nests and roost sites. Prefers edges of woods and areas where cultivation, meadows , pastures, or moors alternate with coniferous or deciduous woods, or at least clumps of trees. In overwintering range, extends into areas with very few trees, such as open fields, steppe, or wetlands (53). Mainly flat terrain or gentle slopes at low or moderate elevations (sea-level to 2000 m) (27); also in mountains, where in summer may forage above tree line. Regularly perches on trees, poles, posts, rocks, and pylons.

Dispersal and Site Fidelity

Information needed.

Migration Overview

Migratory in Scandinavia (wintering in southern Sweden), and in most of Russia; partially migratory in central Europe (increasingly so with latitude); mostly sedentary in Britain, southern Europe, Turkey, Caucasus, and in island populations . Overwinters in Africa, Israel and Arabia; easternmost breeding populations winter in central Asia and southern India; part of central European population moves south and southwest in autumn, with some migrants reaching northwest or even western Africa. Large numbers enter the Iberian peninsula to winter but very few continue south as far as northwestern Africa, although several thousand used to do so in the 1970s (54).

<em>vulpinus</em> completely migratory, traveling up to 13,000 km, to winter in southern Europe and southwest Asia, but mainly in sub-Saharan Africa , particularly in south; crosses over to Africa mainly via Bab al Mandab Strait (between Yemen and Djibouti) in autumn, and returns by Suez in spring; e.g., 465,827 birds recorded at Eilat, Israel in spring 1986 (55). B. b. menetriesi apparently non-migratory.

Length of migrants' absence from breeding grounds increases with latitude. Twelve birds equipped with satellite transmitters on their nesting grounds in central Sweden departed for the wintering grounds from late September–late October; 8 wintered in Denmark (425–692 km distant) and 1 each in southern Sweden (452 km), Germany (702 km), Netherlands (1,187 km) and Belgium (1,449 km); 4 adults whose transmitters functioned all winter returned to their nesting grounds from mid-March to early April the following spring, moving at an average speed of 51–148 km/day (56).

Feeding

Main Foods Taken

Variable, adapts its diet according to local and seasonal availability (57). Mainly include small mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, large insects, and worms (1).

Microhabitat for Foraging

Hunts in clearings and open areas near edges of woods; almost always captures prey on ground.

Food Capture and Consumption

Spends long periods perched , scanning or loafing; also spots prey from gliding or soaring flight; sometimes hovers or hangs on wind; also walks on ground when stalking invertebrates.

Diet

Major Food Items

Essentially a hunter of small mammals which often constitute up to 90% or more of prey; particularly rodents, with voles main prey over much of range; also mice, rats, hamsters, shrews, moles, young rabbits and hares; where abundant, rabbits can be locally important. At a study area in Ireland where voles were absent, diet consisted mostly of European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus), and medium-sized birds (especially corvids) (58).

Birds can be important by mass, particularly when mammals are scarce; occasionally, species up to size of pigeon, pheasant, partridge, and Barn Owl (Tyto alba) (59) are taken, but during summer diet mostly includes nestlings and fledging, sporadically adults; the species recorded are European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris), thrushes, crows, tits, finches, buntings, larks, and woodpeckers; also young of Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), Gray Partridge (Perdix perdix), and domestic chicken (1).

Reptiles mostly include lizards (Lacerta) and slow-worm (Anguis fragilis), occasionally snakes such as grass snake (Natrix natrix), ladder snake (Elaphe scalaris) and vipers (Vipera). One case of a bird capturing a live European eel (Anguilla anguilla) (60). Amphibians can be important prey items and include frogs (Rana) and toads (Bufo, Pelobates, Bombina) (1).

Sometimes invertebrates dominate prey items by number, such as beetles, crickets, locusts and earthworms. At times scavenges carrion, including medium-sized mammals, such as sheep, but also rabbits (2). In one instance, observed eating an apple of the dessert variety, "slightly bruised but not rotten" (61).

Quantitative Analysis

During winter, one study on a Scottish grouse moor, showed in the first year of data collection, that of 409 pellets collected, the most frequent items were small mammals 88%, followed by invertebrates (predominately beetles) 34.7%, lagomorphs (European rabbit and brown hare [Lepus europaeus]) 21.8 %, Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) 5.4%, Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus) 2.9%, other birds (Corvidae and other passerines, Columbidae), and unidentified bird remains 9.3% (62).

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Main call a loud plaintive mewing squeal “kyaaah” , about 0.5–1 second long and quickly dropping in pitch, sometimes with a notably wavering voice. Main call has many slight variations, all possibly used in a specific context (sharper, more ringing in aggression, drawn-out and wavering when chasing intruder, sharper, more yelping when approaching nest, and shorter, more explosive in alarm) (27) . Also a faster series of yelping squeals.

Phenology

Pair Formation

Sky dancing (courtship) is most frequent in March‒April and July‒October (1).

In Netherlands one study recorded onset of pair formation by late February (63).

Nest Building

Starts two months before laying (1). In the Netherlands, a pair were seen repairing a Eurasian red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) drey which took place from late February to mid-April, and built two new nests from early March to early April and mid-April (63). In New Forest, England, pairs start to add new material to the nest by the end of February, finishing by mid-March (64)

First Brood

One brood per season, however replacement clutches are smaller and normally laid after the first clutch is lost (1). Eggs laid late March and early April in southern Europe, in northern range late May and early June (1).

Nest Site

Selection Process

Both male and female seems to share the selection of the site. Pair usually occupies the same area for multiple seasons, repairing old nests or reusing nests built by other species (e.g., dreys of Eurasian red squirrel) (63).

Site Characteristics

In lowlands, breeds in woodlands, often at edges, building its nests on taller and more mature trees, whereas in highland areas where taller trees are scarce, the nest might be built on cliff ledges (65, 2). Others unusual nesting places has also been recorded such as in an abandoned building in Spain (66) and Scotland (2), and on the ground at the edge of a drainage ditch in Scotland (2).

In woodlands, preferred nest sites are usually large mature trees and also those that can provide natural cover such as individuals covered in ivy or evergreen species, but according to Walls and Keeward (2) the site selection is more dependent on what choices are available locally. In does not appear to show a preference for certain tree species; in Poland (n = 54 nests) 56% of nests were built mixed-deciduous forest and 44% in pine forest (67), pairs also showed preference for larger and older nest trees and for nests to be closer to forest openings and alder woods. In central Italy (n = 15 nests), 33% of nests were sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa), 20% in black pine (Pinus nigra), and 13% in turkey oak (Quercus cerris).

In northern areas such as Norway where the snow lasts longer during the spring, Common Buzzard showed preferences for areas with south-facing slopes and in steep terrain where they are snow free and voles might be available for hunting (68).

In Scotland, 50 nests studied were placed 4.6–21.4 m (mean 11 m) above ground (69). Within the nest tree, the nest is generally located 3–25 m above ground, usually near the main trunk (1).

Nest

Construction Process

Built by both sexes. In the New Forest, England, the material used to build the nest was probably taken from the vicinity of the nest tree (64). Within the nest tree, the nest is normally placed close to the main trunk at 3–25 m above the ground (1), but lateral branches can also be used. One study in Poland found that 87% (n = 15) of nests in a deciduous forest were built in the fork of the main trunk, whilst in coniferous forests 39% of the nests (n = 18) were placed in the fork, 17% were built on lateral branches, however, 22% of the nests were built at least 1 m from the main trunk (70).

Structure and Composition

Nest is a bulky platform of sticks and twigs, lined with greenery (1). At nests in the New Forest, England, materials used were mainly dead plant material, with a lining of branches and twigs collected from living trees such as Scotch pine (Pinus sylvestris), birch (Betula), larch (Larix), oak (Quercus), beech (Fagus), and ash (Fraxinus) (64).

Dimensions

In Scotland, 50 nests studied averaged 1 m in depth and diameter (69).

At the New Forest, England, a nest used for 13 consecutive years was 1.5 m diameter and 0.7 m in depth (64).

Maintenance or Reuse of Nests

A nest can be used for many years, even if new nests are built. The nest maintenance is continuous throughout the breeding period (2)

Nonbreeding Nests

The pair keep a number of nests built in their territory and even if only one nest is used consecutively, the others nests are repaired and fresh material is added during the breeding period (2).

Eggs

Data from Cramp and Simmons (1).

Shape

Rounded and oval.

Size

- B. b. buteo 50–64 × 39–48 mm (mean 55 × 44 mm, n = 600).

- B. b. vulpinus 48–63 × 39–48 mm (mean 54 × 43 mm, n = 303).

- B. b. rothschildi 53–58 × 42–44 m (mean 56 × 43 mm, n = 12).

- B. b. arrigonni 51–57 × 39–45 mm (mean 53 × 43 mm, n = 8).

- B. b. menetriesi 51–56 × 40–44 mm (mean 53 × 42 mm, n = 12).

Mass

- B. b. buteo 47–55 g (mean 51 g, n = 26); 46–61 g (mean 55 g, n = 32).

Color and Surface Texture

Not glossy, white with variable red and brown.

Clutch Size

Normally 2–4 eggs (range 1–6).

Egg Laying

The interval between eggs is typically 3 days.

Incubation

Onset of Broodiness and Incubation in Relation to Laying

Incubation begins with the first egg laid, the male may incubate, but most of the time the eggs are incubated by the female (1).

Incubation Period

At the New Forest, England, the average incubation period is 33 days per egg (64). The average in United Kingdom is 36–38 d and elsewhere in Europe 33–35 d (see in 1).

Parental Behavior

Both parents share in incubation, however the female spends more time incubating whilst the male brings food for her (64).

Hatching

Hatching is asynchronous; at New Forest, England, there was an interval of 48 hours between eggs (64).

Young Birds

Condition at Hatching

Down long and sparse, with white or brown-gray upperparts and white underparts, darker around the eyes (see 1).

Growth and Development

In New Forest, England, the chicks at day 1 weighed 40‒45 g, by the third week the chicks were reported to weight ten times more and by the fifth week the chicks were reported to have doubled their weight, and therefore almost reaching an adult weight (64).

Parental Care

Brooding

Brooding is carried out by the female, continually for about 7 days, but when the chicks are around 14 days old the female will leave the nest for longer periods (64, 1).

Feeding

The male will feed the female and chicks for the first 2 weeks after hatching, but by the time the chicks are about 4 weeks old, the female will be responsible for the majority of food brought to the nest (64).

Nest Sanitation

Carried out by the female for at least the first 2 weeks after hatching (2 ).

Fledgling Stage

Departure from the Nest

In the New Forest, England, chicks were estimated to fledge at 49‒60 days old (64). In Dorset, United Kingdom, another study recorded that chicks fledged at 43‒54 days old (71).

Growth

In Dorset, the primaries molt was completed around 65 days after hatching (71).

Association with Parents or Other Young

Both parents will feed the young until 6‒8 weeks later, although sporadically (64).

Ability to get Around, Feed, and Care for Self

In Dorset, United Kingdom, one study found the fledglings would increase their distance from the nest after they were 65 days old, after the complete molt of the primaries (71).

Population Status

Among the most common and widely distributed of Palearctic raptors. Increasing population trends since at least the 1980s, perhaps 800,000–850,000 pairs in western Palearctic, including 500,000 pairs in European Russia and 140,000 pairs in Germany (27). B. b. insularum of Canary Islands increased from around 425–450 pairs in 1988 to around 500 pairs in 2001, despite continued threats from poisoning, nest-robbing and illegal shooting (72). At study area near Avon, England, the number of nesting pairs rose from 13 in 1982 to 105 in 2012, the increase in part resulting from a generally positive attitude toward raptors that began in the late 1970s (73).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Thought to be the second or third most common raptor in Europe, with increasing population trends since at least the 1980s.

Effects of Human Activity

Historically, important causes of declines were direct persecution; populations also affected by use of poisoned baits and pesticides, habitat loss and increasing rarity of prey.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding