Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix Scientific name definitions

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Albanian | Gjeli i egër bishtlirë |

| Bulgarian | Тетрев |

| Catalan | gall cuaforcat |

| Chinese (SIM) | 黑琴鸡 |

| Croatian | tetrijeb ruševac |

| Czech | tetřívek obecný |

| Danish | Urfugl |

| Dutch | Korhoen |

| English | Black Grouse |

| English (United States) | Black Grouse |

| Faroese | Orri |

| Finnish | teeri |

| French | Tétras lyre |

| French (France) | Tétras lyre |

| German | Birkhuhn |

| Greek | Λυροπετεινός |

| Hebrew | שכווי שחור |

| Hungarian | Nyírfajd |

| Icelandic | Orri |

| Italian | Fagiano di monte |

| Japanese | クロライチョウ |

| Latvian | Rubenis |

| Lithuanian | Tetervinas |

| Mongolian | Хар хур |

| Norwegian | orrfugl |

| Polish | cietrzew |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Tetraz-lira |

| Romanian | Cocoș de mesteacăn |

| Russian | Тетерев |

| Serbian | Ruševac |

| Slovak | tetrov hoľniak |

| Slovenian | Ruševec |

| Spanish | Gallo Lira Común |

| Spanish (Spain) | Gallo lira común |

| Swedish | orre |

| Turkish | Orman Horozu |

| Ukrainian | Тетерук євразійський |

Lyrurus tetrix (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- LYRURUS

- lyrurus

- tetrix

- Tetrix

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

Male c. 60 cm, 1100–1250 g (up to 2100 g); female, c. 45 cm, 750–1100 g. Glossy black , with blue or green reflections, contrasting with white in rounded carpal patch, prominent wingbar and undertail-coverts; peculiar lyre-shaped tail , with outer feathers long and curved outwards ; scarlet combs . In late summer, feathers on head and neck mottled or barred brown, and some white on throat. Female largely brown , heavily barred black; darker than Tetrao urogallus, with thin white wingbar and shorter tail, slightly forked when closed. First-winter like adult, but male browner and duller, with outer tail feathers less curved; in both sexes, two outermost primaries more sharply pointed and more vermiculated at tips. Males only achieve full size when three years old, but females at two. Races vary clinally in size, colour of gloss in male and general coloration of female: race britannicus is overall darkest and smallest, with the smallest area of white in the wing; viridanus has most white in wing, the tail feathers have white bases in 50% of males and 60% of females, metallic gloss on breast is more green than violet, males have brown streaks on upperparts, while most females have an obvious white gular patch, a red-brown breast and black-brown patch on central belly; race baikalensis is a large race, with males having a pale blue gloss and females having paler, cross-barred underparts than mongolicus; race mongolicus is more dark brown above and are darker grey and streaked below; and male of race ussuriensis is smaller than baikalensis and lacks streaks on upperparts, and females are darker and more intensely red-brown.

Systematics History

Editor's Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Often placed with closely related L. mlokosiewiczi in genus Tetrao. Commonly hybridizes with Tetrao urogallus, and quite often with Lagopus lagopus, both hybrids even receiving vernacular names; also occasionally with Lagopus muta and Bonasa bonasia. Geographical variation clinal: race tschusii often included in viridanus, but likely an intergrade; baikalensis sometimes subsumed within ussuriensis. Proposed race fedjuschini (from NW & N Ukraine) included in nominate. Review of subspecies required. Seven subspecies currently recognized.Subspecies

Lyrurus tetrix britannicus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Lyrurus tetrix britannicus Witherby & Lönnberg, 1913

Definitions

- LYRURUS

- lyrurus

- tetrix

- Tetrix

- britanica / britanniae / britannica / britannicus / brittanica

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Lyrurus tetrix tetrix Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Lyrurus tetrix tetrix (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- LYRURUS

- lyrurus

- tetrix

- Tetrix

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Lyrurus tetrix viridanus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Lyrurus tetrix viridanus (Lorenz, 1891)

Definitions

- LYRURUS

- lyrurus

- tetrix

- Tetrix

- viridana / viridanum / viridanus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Lyrurus tetrix tschusii Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Lyrurus tetrix tschusii (Johansen, 1898)

Definitions

- LYRURUS

- lyrurus

- tetrix

- Tetrix

- tschusii

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Lyrurus tetrix baikalensis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Lyrurus tetrix baikalensis (Lorenz, 1911)

Definitions

- LYRURUS

- lyrurus

- tetrix

- Tetrix

- baicalensis / baicalicus / baikal / baikalensis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Lyrurus tetrix mongolicus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Lyrurus tetrix mongolicus (Lönnberg, 1904)

Definitions

- LYRURUS

- lyrurus

- tetrix

- Tetrix

- mongola / mongolica / mongolicus / mongolus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Lyrurus tetrix ussuriensis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

Lyrurus tetrix ussuriensis (Kohts, 1911)

Definitions

- LYRURUS

- lyrurus

- tetrix

- Tetrix

- ussuriana / ussurianus / ussuriensis

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Western Capercaillie x Black Grouse (hybrid) Tetrao urogallus x Lyrurus tetrix

Distribution

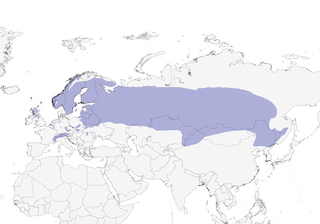

Editor's Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the 'Subspecies' article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Highly variable throughout wide range, but typically found in transition area between forests and open environments , e.g. steppes, heaths, moors , bogs and marginal cultivation (e.g., hayfields occasionally used for brood-rearing) (1), and seasonal changes in habitat use only appear to occur at S edge of range. From N edge of boreal forest to brushwood steppe zone or locally semi-desert, e.g. in W Kazakhstan; in lowlands and mountains, up to 2000 m in Alps, 3000 m in Tien Shan. In N Europe, deciduous or mixed forests preferred to coniferous ones, and sparse, young stands to older, denser ones; but in S mountains, e.g. Alps, mainly occupies moderately dense forest of spruce and fir, or larch. In many areas appears to select birches (Betula pubescens, B. verrucosa). Good breeding habitat usually contains a high diversity of plants; a study in SE Norway that compared present species and Tetrao urogallus found that broods of the latter were more frequently recorded in bilberry-dominated forest types, whereas those of L. tetrix preferentially used pine bog forest (2). In Scotland, wet habitats are important for young chicks, brood-rearing females selecting relatively tall field-layer vegetation comprising heather (Calluna vulgaris), sedges and grasses over a layer of Sphagnum mosses (3).

Movement

Largely sedentary, although apparently eruptive in some N areas at long intervals, when large flocks (females heavily outnumbering males) may move hundreds of kilometres, provoked by potential food shortages; furthest recovery > 1000 km, in Sweden, and overall the species is distinctly more mobile than other forest-dwelling grouse within the Palearctic. Elevational movements in winter reported in some parts of range, in response to food shortages or to escape snowbound regions (4). Regular winter migrations reported in parts of Siberia (Ussuri, Amur). In Norway, males recovered at 1·6 km on average, females at 4·4 km, with similar patterns recovered elsewhere in range (see also Breeding), and evidence from some parts of range that such greater female dispersal is important for preserving gene flow (5). In general, daily movements limited, but in steppes of N Kazakhstan, regular flights of up to 30 km said to occur and there are also reports of 25 km-long flights over open water. However, individual territories of males in parts of W Europe can be very large, up to 90–120 ha in Alps and even 303–689 ha in Scotland and the Netherlands, whereas females, at least those with broods, can be confined to much smaller areas, e.g. just 2–4 ha in W Russia, though in general, e.g. Scotland, females have seasonal ranges > 70 ha (6).

Diet and Foraging

In many places, favourite winter food is birch catkins, followed by birch buds and shoots, and needles, cones and male flowers of conifers, e.g. Pinus sylvestris and P. mugo, with daily dry weight of 100–120 g of food being taken. In less snow-covered areas in S of range, e.g. England (7, 1), Scotland and Netherlands, greater winter use of shrubs (Calluna, Rhododendron, Vaccinium) and grasses, while in European Alps (where birch is rare) evergreen stems of blueberry, larch twigs and rhododendron leaves are often main constituents of diet (though mountain pine Pinus montana uncinata needles are locally very dominant) (8), while pine needles and cones are principal foods on Kola Peninsula, in N Urals, W Siberia and Transbaikalia. During spring , importance of birch declines in favour of berries, stems and shoots of Vaccinium myrtillus, V. uliginosum, V. vitis idaea, Empetrum nigrum, Calluna vulgaris, Juniperus communis, Polygonum viviparum, Eriophorum vaginatum (9), etc., but in forest zone winter foods remain prominent in diet until as late as Jun. Chicks of < 100 g eat mostly insects, especially ants, with much smaller quantities of tender green grass, seeds and berries; older ones switch to berries, drupes, nutlets, etc., thus while insects comprise 76% of diet in 12-day-old chicks in W Europe, they represent just c. 6% at age two months, and in Finland by Sept insects compromise 15–22% of diet of juveniles; in Norway, insects dominated diet of young until 14–15 days old, whereas young Tetrao urogallus in same region continued to be heavily reliant on such prey for twice as long (2). In France, insects included hymenopterans, orthopterans, coleopterans and larvae (10), with sawfly larvae being especially favoured in parts of Britain (11, 1). Autumn diet in Italy, most frequently included shoots of Vaccinium myrtillus, buds and leaves of Rhododendron ferrugineum, shoots of Larix decidua, fruits of Sorbus spp., and stems, leaves, fruits, and seeds of herbaceous species (e.g. Geum spp., Galium spp., Anemone spp.) (12), while in N England leaves and stems of Calluna vulgaris formed bulk of diet of both sexes (9). Shift to tree-feeding in winter is probably related to amount of food on ground, leaf conditions of trees and weather and snow conditions. Year-round study in N England found that plant fragments represent 98% of diet and include 53 plant species or taxa, with invertebrates comprising other 2%, but diet varies significantly between seasons and sexes, with both sexes consuming more ericaceous shrubs in autumn/winter, especially by females, while plant parts eaten vary seasonally, thus in summer, fruits, flowers and seeds are favoured over leaves, whereas latter dominate in winter (13). Forms flocks from mid autumn, with extent and nature of flocking varying regionally, in W Russia numbering up to 300 birds of both sexes, whereas in W Europe flocking is generally restricted to young males and females of all ages, yet in S Urals most flocks comprise adult males.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

During display at communal leks , males emit a resonant, dove-like rhythmic phrase starting with a bubbling trill that increases in volume and is typically followed by two double coos , e.g. “bububububrrru!..curr-curr..curr-curr”, repeated continuously for long periods and audible at distances of up to 3·5 km, with some regional variations reported, e.g. song is longer in parts of Russia than in Sweden, and quieter in the Tien Shan than the plains. Male also give drawn-out hissing screeches, “khahweeee” or similar, in different contexts, including a low, guttural “ghuk...ghuk...ghuk” in presence of terrestrial predator, or “tiutt-tiutt-tiutt-tiutt ... tiut” when danger is aerial. Female utters short resonant clucks, “kwuk..kwuk..kwuk…” to reassure brood of chicks, or low , guttural “krruagg” in alarm, when together in flocks.

Breeding

Lays May–Jun. Promiscuous or polygamous; males form leks , which are maintained between the start of the breeding season (typically Mar) and hatching (but also in autumn/early winter) (14, 15), and sited in open areas but never far from forest, or tall thickets in forest-steppe zone; formerly attended by up to 200 individual males , but generally much smaller numbers now, and regularly even lone males (16, 17, 18); sites generally change in no more than ten years. Apparently rare for females to mate with more than one male (19). Strong natal philopatry is suspected for males alone (20) as, for example in French Alps, 81% of females nested 5–29 km from their site of capture the previous autumn (21), with dispersal of young often occurring in two separate waves, in autumn and spring (22). Nevertheless, despite male philopatry, genetic studies have recorded no evidence of relatedness among males attending a given lek (23). Nests amongst scrub or tall vegetation, often at base of tree, between roots, under low branches or against a boulder, exceptionally in an old nest beloning to a raptor or corvid, 7 m above ground; nest a shallow scrape, 23–28 cm wide by 10–11 cm deep, usually lined with some plant material and feathers. Replacement clutches are typically laid further from the first nest than nests in the following season by a female that had been successful (24); in N England, females typically nested within 0·25 km of the previous year’s site, irrespective of success (25). Mean eight eggs (6–11) in Finland, but repeat clutches typically substantially smaller, laid at intervals of 1·5 days; eggs yellow to pale ochre spotted brown, size 46–58·4 mm × 33·2–42·8 mm, mass 28·8–40·9 g; incubation 23–28 days by female alone; downy chick has brown cap surrounded by black line, reminiscent of Lagopus, hatch weight 24–25 g; flight feathers develop from first day, and chicks capable of flight at 10–14 days; first primary shed at c. 15 days. Recorded parasitizing nests of Tetrao urogallus and Lagopus lagopus, while Perdix perdix has been reported egg-dumping in nests of present species (26). In two studies in Finland, 71% clutches hatched and 62% chicks survived until late Aug, with other studies in both Finland and France reporting that first-year females generally fared less well than adults (27, 28). Reproductive success to some extent determined by prevailing weather conditions (17) (with low temperatures being especially negative) (29), while unusually harsh winters (e.g. with prolonged snow cover) can have strong negative consequences for survival (30). Sexual maturity in first year, but males probably rarely mate even during second. Annual survival rate 40–60% (Finland) or 52–68% (French Alps), with most deaths due to predation, especially by Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), Northern Goshawks (Accipiter gentilis), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), pine martens (Martes martes), stone martens (M. foina) and stoats (Mustela erminea) (31, 32, 33, 22, 34, 35, 36); one ringed female survived at least 5·5 years. Predation accounts for c. 75% of total deaths in W Russia (37).

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). Major declines and range contractions reported throughout Europe, except in Alps and N, although even in former decreases have been reported in Switzerland (38) and N populations generally follow 4–10-year cycles (39), or did, as recent evidence suggests that these no longer exist in NE Finland (40). Following some expansion during 19th century, species presently very scarce in most of W & C Europe, especially in lowland areas: e.g. in Denmark from c. 2500 birds in 1964 to 280–360 in 1977 and the species became extinct there in mid 1990s (39); in Netherlands from c. 3000 birds in 1964 to 280–360 in 1977, with < 50 at present (39, 41). In Britain, declines of up to 93% suspected in N England and Scotland since 1900s (42), with an estimated population of 6510 males in 1995/96 (43), just 773 males in England in 1998, where a conservation recovery programme was established in 1996 (44), then 5078 displaying males in 2005 (at which point numbers in Scotland were declining, but those in Wales were increasing) (45), while 1029 males were registered in N England in 2006 (thus also increasing) (46) and, most recently, 1437 males in 2014 (47). In Alps , where typical densities appear to be 1·5–7 males/km², population may be stable: < 1000 pairs in France, c. 40,000 birds at end of summer in Italy, c. 14,000 birds in Austria and 850–1400 territories in Germany, where population was until recently in decline (48, 49, 50). Much commoner, although also decreasing, in Fennoscandia, with possibly 500,000 birds in Norway (where numbers estimated to have decreased 20% since 1971) (51), c. 300,000 pairs in Sweden , and c. 900,000 pairs in Finland, where densities may average 1–3 males/km² (see also below). In Russia, numbers and range diminishing in S, but apparently increasing in N. In Ukraine, now scarce, occurring only in Poles’ye zone and Carpathians; protected in many areas, and species not hunted. Maximum densities of up to 30 birds/km² in autumn reported in S Finland and W Russia in mid-20th century, but now much lower. Status in E Asia poorly known, e.g. in China, where it is protected in some areas, including Sanjiang Nature Reserve, Heilongjiang (52), although numbers wintering in Hebei are apparently declining (53) due to hunting pressure and low breeding success (54); species has only recently (2002) been discovered in South Korea (39). Logging in mature woodland tends to favour present species, but increased cultivation, afforestation of heathlands, removal of birch stands and imposition of coniferous monocultures have negative effects, and declines in parts of UK have been strongly linked to forest maturation (55). Locally, species also suffers from excessive hunting, disturbance at leks and other factors; for example, in Scandinavia, collisions with high-tension powerlines may kill > 26,000 birds annually in Norway (39). In the Italian Alps, winter sport disturbance has been shown to increase stress hormone levels, what may reduce resistance to disease (56), and conflicts between this species and winter sports have also been reported in Germany (57). Climate change represents a newly recognized threat in some regions; for example, in Finland, the species has responded to spring warming by advancing both egg-laying and hatching, but chicks now face colder post-hatching conditions and are increasingly suffering higher mortality as a result of hatching too early, with the net result that breeding success and population size have both severely declined over the past four decades (58); however, climate warming does not appear to be having such negative affects in the Alps (59). Hunting figures, mostly from late 1970s, include annual bags of 1200–1500 males in Switzerland, 1700 males in Austria, 1200–1600 males in Poland, 19,000 birds in Norway, 21,600 in Sweden and 54,000–171,000 in Finland, with a Swiss study revealing that permit issuance has greatest effect on numbers taken (60). In C Europe mainly hunted in spring. Predation accounts for c. 75% of total deaths in W Russia (37).

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding