Gallus

Etymology: Rooster

First Described By: Brisson, 1760

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Pangalliformes, Galliformes, Phasiani, Phasianoidea, Phasianidae, Pavoninae, Gallini

Referred Species: G. aesculapii, G. moldovicus, G. beremendensis, G. tamanensis, G. kudarensis, G. europaeus, G. imereticus, G. meschtscheriensis, G. georgicus, G. varius (Green Junglefowl), G. sonneratii (Grey Junglefowl), G. lafayettii (Sri Lankan Junglefowl), G. gallus (Red Junglefowl and Domesticated Chicken)

Status: Extinct - Extant, Least Concern

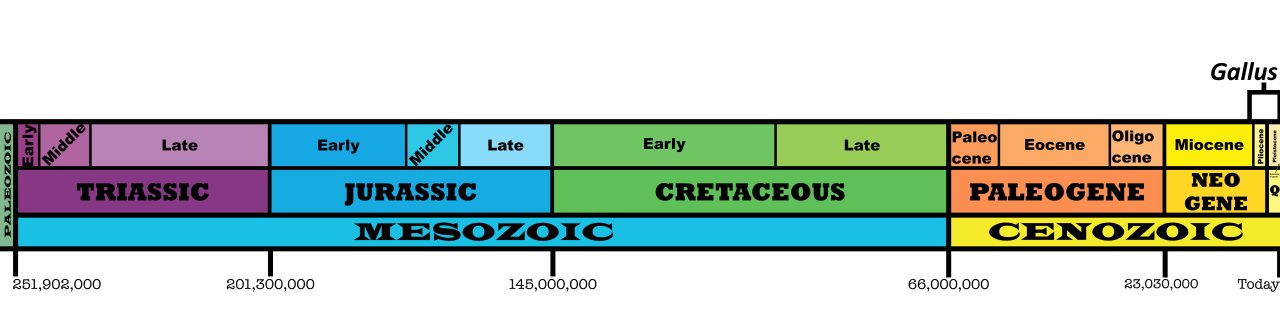

Time and Place: Since about 6 million years ago, in the Messinian of the Miocene through today

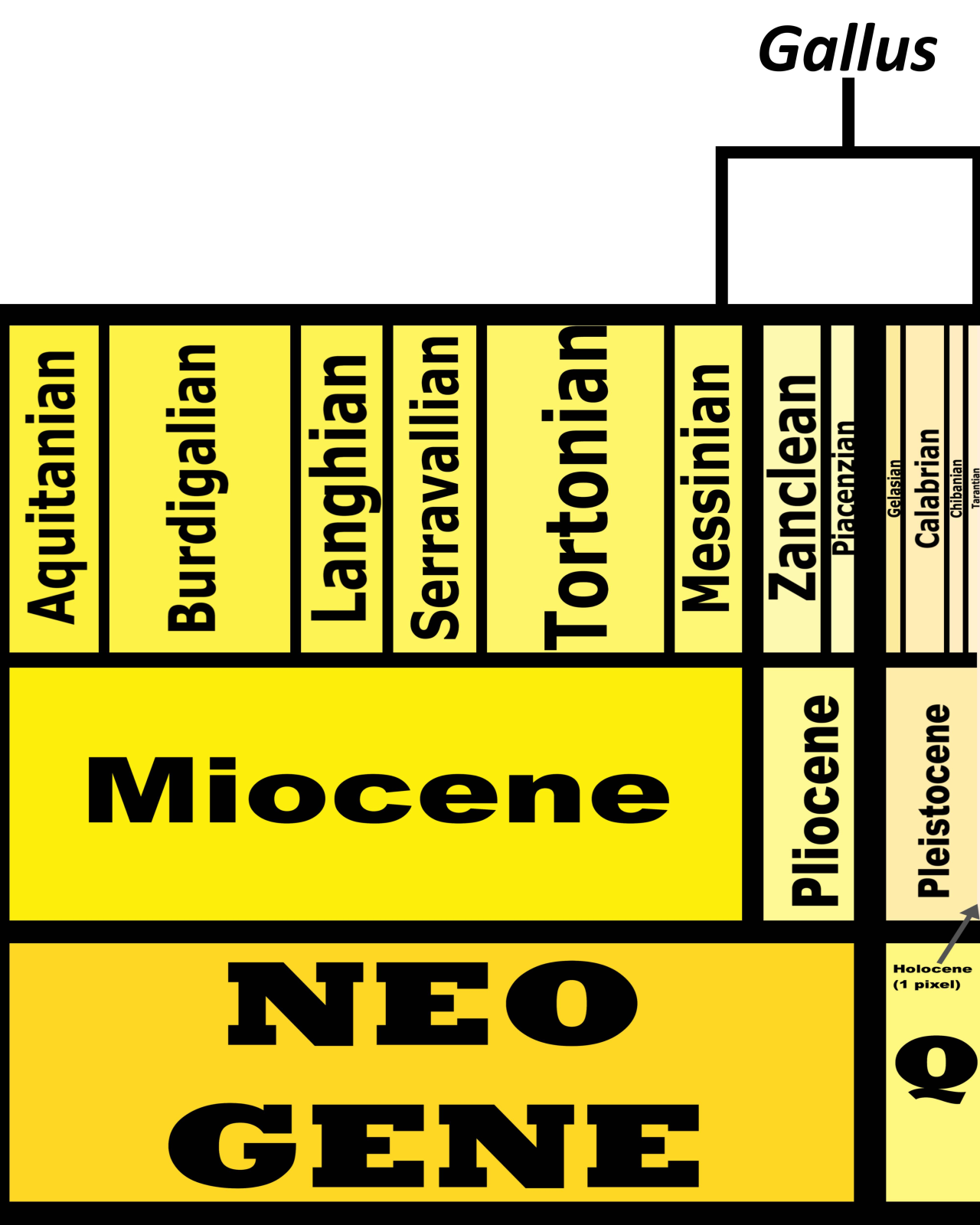

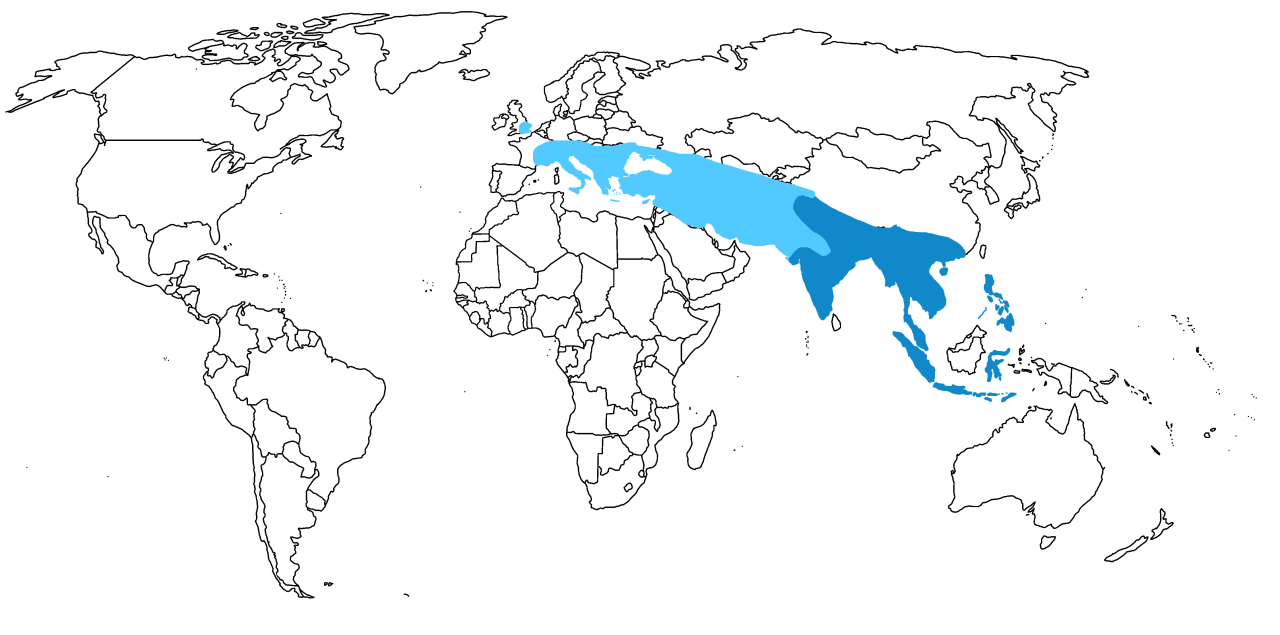

In the past, Junglefowl were found throughout Eurasia, especially across Europe. After the last glacial maximum, they were restricted to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Eurasia, as well as many Pacific islands. Of course, today, domestic chickens are found all over the world. This map below shows the current range of wild Junglefowl in dark blue, and extinct Junglefowl in light blue; please note that domesticated and feral chickens are found everywhere.

Physical Description: Junglefowl are highly ornamented, beautiful, bulky birds, with the males being decorated in brilliantly iridescent feathers all over their bodies. The females tend to be more dull in color, in order to blend in with the environment; that being said, they can also have beautiful and distinct patches of brighter feathers in certain strategic places, such as the tail. The males also have combs on the tops of their heads, made out of skin and muscle, rather than feathers; they also tend to have bare red faces, and wattles underneath their chins also made of skin and muscle. Their tails tend to have long, curved ribbon feathers, colored with iridescence and usually in a blueish-greenish shade. The tails of the females are shorter and less distinctive. These birds are squat, with short legs and bulky bodies. They also have small heads and short, pointed beaks. In general, junglefowl males can range between 65 and 80 centimeters long; the females tend to be significantly smaller, ranging between 35 and 46 centimeters long.

Sri Lankan Junglefowl by Schnobby, CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: Junglefowl are omnivorous birds, feeding on a wide variety of food such as such as insects, worms, leaves, berries, seeds, fruit, bamboo, grasses, tubers, and even small reptiles.

Grey Junglefowl by Yathin S. Krishnappa, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: Junglefowl tend to forage in small groups, but they will also scratch around the ground for food alone, using their feet to release food that might be trapped under the most shallow layer of ground or leaf litter. They peck, very distinctly, at the ground - bobbing their bodies back and forth as they move around, pecking in short spurts to gather the food they look for. They are very opportunistic feeders, switching back and forth between different food sources based on what is more available in a given season. They can even associate, happily, with other birds and even mammals of all things, using the environmental disturbance they cause in order to find food.

Green Junglefowl by Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Junglefowl make some of the most distinctive calls of any bird, though of course, each language seems to have its own onomatopoeia to describe it. They make very distinctive clucks, cackling, and even cooing sounds depending on the situation. Males do make “cock-a-doodle-do” calls, though they can vary in tone and loudness, as well as the syllables involved, from species to species. These calls are actually advertising calls, made by the males, in order to attract females! The females tend to be quieter than the males, though domesticated female chickens are not quiet animals by a longshot. Junglefowl do not migrate, and tend to stay limited within their preferred habitats (though, of course, domesticated chickens have been bred to deal with a wider variety of climate better than their wild relatives.)

Red Junglefowl by Harvinder Chandigarh, CC By-SA 4.0

Junglefowl can breed throughout the year (it’s why they were domesticated), though some populations tend to favor the dry season over the wet season (primarily due to less danger with the daily weather - these guys do hail from the monsoon lands!) As a general rule, junglefowl are polygamous - males will mate with a variety of females throughout the year, with the females doing the bulk of the work in nest construction and child care (which makes sense, since they blend in so well with the environment). Some species - such as the Grey Junglefowl - do show monogamous behavior from time to time, with males sticking with one female for long periods of time. In a classic case of sexual selection, females tend to prefer males with more brilliant combs (rather than focusing on plumage color, though this could be different in non-domesticated species). The female will lay between 2 and 6 eggs (some species laying more than others) in a depression amongst dense vegetation; the female will incubate the eggs for three weeks before the chicks hatch. The chicks are extremely fluffy and cute when hatching, usually covered in soft brown feathers (though domesticated ones are more yellowish). The chicks are able to fly after one week, and males will become sexually mature sometime between 5 and 8 months. They are not the strongest fliers, usually preferring short bursts of activity rather than sustained flight.

Domesticated Chicken Chicks by Uberprutser, CC BY-SA 3.0

Extremely social birds, chickens have a very noticeable pecking order - with individual chickens dominating over others in order to have priority for food and nesting location. This pecking order is disrupted when individuals are removed from a flock; adding new chickens also causes fighting and injury until a new pecking order is established. This family structure was exploited by early humans, in order to become the “top chicken” and domesticate the species. Interestingly enough, chickens do gang up on inexperienced predators - foxes have even been killed in such encounters! Despite stereotypes to the contrary, chickens are extremely intelligent animals - studies have shown they have higher intellectual capabilities than human toddlers - they are self aware, are able to count, and do trick one another into actions (aka, they can lie and manipulate other chickens). What’s more, despite their pecking order fights, they are very affectionate and empathetic birds - prone to cuddling with other flock members, and checking in to make sure the flock is alright. They show very rapid learning ability, and are able to grasp basic number theory only after a few weeks from hatching. In addition to being logical with numbers, they can reason out many other things - including forming teams to play kickball! Bird-brain, indeed!

Red and Green Junglefowl by Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecosystem: Junglefowl primarily live in dense, humid rainforest and wet woodland. They can also be found in savanna, scrub habitat, coastal scrub, mountain forest, and also in human plantations and farmland (as wild species spreading into human-created habitat). They do prefer lower elevations to higher ones, as a general rule. They are fed upon by a wide variety of creatures - larger birds, predatory mammals, and large lizards and crocodilians. Of course, the biggest predator of junglefowl is probably People! Just, statistically speaking.

Sri Lankan Junglefowl by Steve Garvie, CC BY-SA 2.0

Other: Junglefowl are, thankfully, not threatened with extinction. In fact, they are extremely common birds throughout their range. Domesticated chickens even regularly go feral (ie, return to wild living despite being descended from fully domesticated populations), spreading into places far from their original range such as Latin America, Hawai’i, and Africa. There are many extinct species of Junglefowl; they used to have a much wider range into Europe, but went extinct during the last Glacial Maximum, when things got too cold for them everywhere but Southeastern Asia. They then thrived in those jungle habitats, before being domesticated by people during the Holocene.

Domesticated Chicken by Berit, CC BY 2.0

Chickens were domesticated from the Red Junglefowl sometime around 5,000 years ago in Southeastern Asia. It was probably domesticated multiple times - with hybridization occurring afterwards. It spread throughout the world, reaching Greece by the fifth century BCE, though they were in Egypt potentially one thousand years earlier (or even more!!!). They were domesticated due to their frequent laying schedule - made more so by selective breeding, of course - and easily exploitable family structure. They were domesticated to breed even more frequently, leading to an abundance of adult animals - and the females even lay unfertilized eggs, giving us another source of delicious food. They also have been bred to come in many sizes, shapes, and brilliant colors of plumage. Because of their high empathetic capacity, chickens are amazingly good pets - plus, they’re domesticated, which gives them a leg up over parrots. Docile breeds, such as silkies, are great pets for children, including children with disabilities. Chickens are so fundamental to human society, that aphorisms often feature them - and they serve as symbols on heraldry, their feathers are featured in clothing, and it’s hard to escape notice of chickens wherever we go in the world today.

Chickens are the most common bird in the entire world, being bred throughout the world and able to live in harsher climates than their original range (due to domestication and specially designed coops); there are probably over 50 billion members of the genus Gallus present on the planet today. They are so common that they are a model organism - in order to understand birds as a whole, scientists do extensive studies on chickens in order to understand avian evolution. The genes and development of chickens are probably better understood than any other living kind of dinosaur. This is of special interest to members of this blog, as chicken genes have been manipulated to give them teeth (though without enamel) and longer tails - much like their non-avian dinosaur ancestors. One study even raised chickens to walk around with plungers stuck to their butts like a bony tail - and showcased how the chickens changed their head-bobbing and walking to match the redistributed weight, which makes a decent hypothesis for how non-avian dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus were able to walk (see above)!

By Scott Reid

Species Differences: Among the living species, there are distinct differences in the coloration of the males. While the females all tend to be brown and black spotted, with some patches of red on the tails and wings in some species, the males have brilliantly different colors all over. Red Junglefowl - the wild kind - are a mid sized species, and are named accordingly for their coloration. The males tend to have reddish orange heads, with green wings and bellies; their backs and back of their wings are alls reddish, though they have brilliantly green tails. Sri Lankan Junglefowl are also reddish, but instead of having green undersides to their wings and green tails, they have blueish-grey feathers in those locations. The Sri Lankan Junglefowl is also one of the smallest living species. The Grey Junglefowl also has greyish-blue tail and wing feathers, except it has a firey orange underbelly and wing top. It has grey feathers all over its body, and orange and white and black speckles on its neck. It is the largest known species. Finally, the smallest species, the Green Junglefowl, is much more than green - it is almost a rainbow of colored feathers! Its tail is green, as is its neck; but the rump tends to be yellow, the top of the wing red, and the wattle and comb aren’t red - but purple, red, yellow, and even blue! Extinct species tend to blur the line between junglefowl and their close relatives such as Peafowl (see the oldest known species, G. aesculapii, above); but in many ways, they differ mainly by living in Europe and Western Asia, rather than Southeast Asia and India.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Ali, A.; Cheng, K. M. (1985). “Early Egg Production in Genetically Blind (rc/rc) Chickens in Comparison with Sighted (Rc+/rc) Controls”. Poultry Science. 64 (5): 789–794.

Ali, S.; Ripley, S. D. Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. 2 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 106–109.

Allen, J.A. (1910). “Collation of Brisson’s genera of birds with those of Linnaeus”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 28: 317–335.

Arshad MI; M Zakaria; AS Sajap; A Ismail (2000), “Food and feeding habits of Red Junglefowl”, Pakistan J. Bio. Sci., 3 (6): 1024–1026.

Berhardt, Clyde E. B. (1986). I Remember: Eighty Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 153.

Brinkley, Edward S., and Jane Beatson. “Fascinating Feathers .” Birds. Pleasantville, N.Y.: Reader’s Digest Children’s Books, 2000. 15.

Brisbin, I. L. Jr. (1969), “Behavioral differentiation of wildness in two strains of Red Junglefowl (abstract)”, Am. Zool., 9: 1072

Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, especes & leurs variétés (in French and Latin). Volume 1. Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche.

Carter, Howard (April 1923). “An Ostracon Depicting a Red Jungle-Fowl (The Earliest Known Drawing of the Domestic Cock)”. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 9 (½): 1–4.

Cheng, Kimberly M. and Burns, Jeffrey T. (1988). “Dominance relationship and mating behavior of domestic cocks–a model to study mate-guarding and sperm competition in birds” (PDF). The Condor. 90 (3): 697–704.

Chickens team up to ‘peck fox to death’“. The Independent. March 13, 2019. Archived from the original on March 15, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017

Collias, N. E. (1987), "The vocal repertoire of the red junglefowl: A spectrographic classification and the code of communication”, The Condor, 89 (3): 510–524.

Condon, T. P., Morphological and Behavioral Characteristics of Genetically Pure Indian Red Junglefowl, Gallus gallus murghi, archived from the original on 29 June 2007.

Dohner, Janet Vorwald (January 1, 2001). The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300138139.

Eriksson, J.; et al. (2008). “Identification of the yellow skin gene reveals a hybrid origin of the domestic chicken”. PLoS Genetics. 4 (2). E1000010.

Evans, Christopher S.; Evans, Linda; Marler, Peter (July 1, 1993). “On the meaning of alarm calls: functional reference in an avian vocal system”. Animal Behaviour. 46 (1): 23–38.

Evans, C. S.; Macedonia, J. M.; Marler, P. (1993), “Effects of apparent size and speed on the response of chickens, Gallus gallus, to computer-generated simulations of aerial predators”, Animal Behaviour, 46 (1): 1–11.

Finn, Frank (1911). The game birds of India and Asia. Thacker, Spink and Co., Calcutta. pp. 21–23.

Fumihito, A; Miyake, T; Sumi, S; Takada, M; Ohno, S; Kondo, N (December 20, 1994), “One subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus gallus) suffices as the matriarchic ancestor of all domestic breeds”, PNAS, 91 (26): 12505–12509.

Fumihito, Akishinonomiya; Tetsuo Miyake; Masaru Takada; Ryosuke Shingut; Toshinori Endo; Takashi Gojobori; Norio Kondo & Susumu Ohno (1996). “Monophyletic origin and unique dispersal patterns of domestic fowls”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93 (13): 6792–6795.

Gaudry, A. 1862. Note sur les débris d'oiseaux et de reptiles trouvés a Pikermi (Grece), suivie de quelques remarques de paléontologie générale. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 19:629-640

Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2017). “Pheasants, partridges & francolins”. World Bird List Version 7.3. International Ornithologists’ Union. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

Green-Armytage, Stephen (October 2000). Extraordinary Chickens. Harry N. Abrams.

Grouw, Hein van, Dekkers, Wim & Rookmaaker, Kees (2017). On Temminck’s tailless Ceylon Junglefowl, and how Darwin denied their existence. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club (London), 137 (4), 261-271.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Lawler, A. (2014). Why Did the Chicken Cross the World?: The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization. Atria Books.

Lehr Brisbin Jr., I., Concerns for the genetic integrity and conservation status of the red junglefowl, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, Drawer E, Aiken, SC 29802 (with permission from SPPA Bulletin, 1997, 2(3):1-2): FeatherSite.

Linnaeus, Carl (1748). Systema Naturae sistens regna tria naturae, in classes et ordines, genera et species redacta tabulisque aeneis illustrata (in Latin) (6th ed.). Stockholmiae (Stockholm): Godofr, Kiesewetteri. pp. 16, 28.

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturæ per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 158.

Liu, Yi-Ping; Wu, Gui-Sheng; Yao, Yong-Gang; Miao, Yong-Wang; Luikart, Gordon; Baig, Mumtaz; Beja-Pereira, Albano; Ding, Zhao-Li; Palanichamy, Malliya Gounder; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2006), “Multiple maternal origins of chickens: Out of the Asian jungles”, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 38 (1): 12–19.

Madge, S.; Philip J. K. McGowan; Guy M. Kirwan (2002). Pheasants, Partidges and Grouse: A Guide to the Pheasants, Partridges, Quails, Grouse, Guineafowl, Buttonquails and Sandgrouse of the World. A&C Black.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Marino, L. 2017. Thinking chickens: a review of cognition, emotion, and behavior in the domestic chicken. Animal Cognition, doi: 10.1007/s10071-016-1064-4.

McGowan, P.J.K., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Green Junglefowl (Gallus varius). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McGowan, P.J.K. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Grey Junglefowl (Gallus sonneratii). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McGowan, P.J.K. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McGowan, P.J.K., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Sri Lanka Junglefowl (Gallus lafayettii). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Morejohn, G. Victor (1968). “Breakdown of Isolation Mechanisms in Two Species of Captive Junglefowl (Gallus gallus and Gallus sonneratii)”. Evolution. 22 (3): 576–582.

Morejohn, G. V. (1968). “Study of the plumage of the four species of the genus Gallus”. The Condor. 70 (1): 56–65.

Nishibori, M.; Shimogiri, T.; Hayashi, T.; Yasue, H. (2005). “Molecular evidence for hybridization of species in the genus Gallus except for Gallus varius”. Animal Genetics. 36 (5): 367–375.

Perry-Gal, Lee; Erlich, Adi; Gilboa, Ayelet; Bar-Oz, Guy (2015). “Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside East Asia: Evidence from the Hellenistic Southern Levant”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (32): 9849–9854.

Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 118.

Peterson, A.T. & Brisbin, I. L. Jr. (1999), “Genetic endangerment of wild red junglefowl (Gallus gallus)”, Bird Conservation International, 9: 387–394.

Piper, Philip J. (2017). “The Origins and Arrival of the Earliest Domestic Animals in Mainland and Island Southeast Asia: A Developing Story of Complexity”. In Piper, Philip J.; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Bulbeck, David (eds.). New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory. terra australis. 45. ANU Press.

Pritchard, Earl H. “The Asiatic Campaigns of Thutmose III”. Ancient Near East Texts related to the Old Testament. p. 240.

Roehrig, Catharine H.; Dreyfus, Renée; Keller, Cathleen A. (2005). Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 268.

Sacci, MA; K Howes; K Venugopal (2001). “Intact EAV-HP Endogenous Retrovirus in Sonnerat’s Jungle Fowl”. Journal of Virology. 75 (4): 2029–2032.

Sherwin, C.M.; Nicol, C.J. (1993). “Factors influencing floor-laying by hens in modified cages”. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 36 (2–3): 211–222.

Siddharth, Biswas (2014). “Gallus gallus domesticus Linnaeus, 1758: Keep safe your domestic fowl from your domestic foul”. Ambient Science. 1 (1): 41–43.

Smith, Jamon. Tuscaloosanews.com “World’s oldest chicken starred in magic shows, was on 'Tonight Show’” Archived February 20, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Tuscaloosa News (Alabama, USA). August 6, 2006.

Smith, Page; Charles Daniel (April 2000). The Chicken Book. University of Georgia Press.

Stonehead. “Introducing new hens to a flock ” Musings from a Stonehead". Stonehead.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2010.

Storer, R. W. (1988). Type Specimens of Birds in the Collections of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. University of Michigan, Miscellaneous publications No. 174.

Storey, A.A.; et al. (2012). “Investigating the global dispersal of chickens in prehistory using ancient mitochondrial DNA signatures”. PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e39171.

“Top cock: Roosters crow in pecking order”. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

Wong, GK; et al. (December 2004). “A genetic variation map for chicken with 2.8 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms”. Nature. 432 (7018): 717–722.